Tags

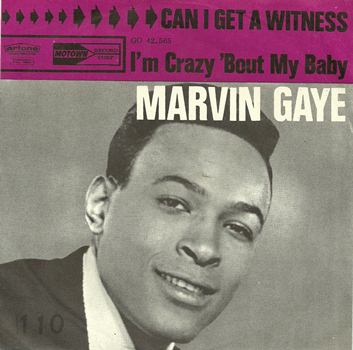

Tamla T 54087 (A), September 1963

Tamla T 54087 (A), September 1963

b/w I’m Crazy ‘Bout My Baby

(Written by Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier and Edward Holland Jr.)

Stateside SS 243 (A), November 1963

Stateside SS 243 (A), November 1963

b/w I’m Crazy ‘Bout My Baby

(Released in the UK under license through Stateside Records)

By the summer of 1963, Marvin Gaye – once a jobbing session drummer and would-be easy listening legend – was a Top Ten recording artist, firmly in the R&B camp. At the same time, the Holland-Dozier-Holland trio were racking up an increasing number of significant chart hits for nearly every Motown act they were assigned to, which meant they got work writing and producing for almost everybody at the label. Their paths were always going to cross sooner or later.

By the summer of 1963, Marvin Gaye – once a jobbing session drummer and would-be easy listening legend – was a Top Ten recording artist, firmly in the R&B camp. At the same time, the Holland-Dozier-Holland trio were racking up an increasing number of significant chart hits for nearly every Motown act they were assigned to, which meant they got work writing and producing for almost everybody at the label. Their paths were always going to cross sooner or later.

In this case, “sooner” is a little bit of a surprise. The prolific HDH team’s overwhelming level of output – so noticeable during Motown’s mid-Sixties Golden Age – raises no eyebrows for having apparently been in play so early, but Marvin’s previous hit single – the rollicking Pride And Joy – had been his Top Ten breakthrough, an excellent consolidation of Gaye’s position as an R&B artist with a stock in trade of uptempo, gutsy numbers. Per later Motown policy, that record’s principal writer-producer, William “Mickey” Stevenson (who wrote Pride And Joy alongside Norman Whitfield and Gaye himself) should have been given the follow-up release. Instead, the new kids on the block jumped straight to the head of the queue with this new composition.

Perhaps Motown thought it was just too good to wait until after Stevenson’s submission (which the recording dates would suggest was probably this record’s B-side, I’m Crazy ‘Bout My Baby) had appeared. Certainly, this was Marvin Gaye’s best single to date.

Motown had long been flirting with the notion of “secular gospel”, the best Motown writers following the likes of Ray Charles and Sam Cooke in incorporating gospel elements into their R&B/pop songs; in recent months, this gospel influence had become more overt, as seen in the likes of Martha and the Vandellas’ Heat Wave and Little Stevie Wonder’s Workout Stevie, Workout. Now, the company’s hottest up-and-coming writers teamed with one of its hottest up-and-coming artists to deliver a knockout punch that succinctly sums up the dichotomy of great Motown in two minutes 48 seconds: an R&B attack on a gospel trope, the combination of church and romance, religious fervour and sexual healing. Who better to lay it down than the son of a preacher man?

That opens up all sorts of questions that space won’t permit us to discuss here, of course. Whole books could – and probably have – been written about how Marvin’s fractious, complex relationships with both his own father and the Almighty would dominate his life (and ultimately end it), so there’s an extra-textual interest to be had in hearing him singing a song based around a phrase that would be immediately familiar to a large percentage of African-American churchgoers, paying homage to the phrase’s origins through the music while landing it in a different context entirely through the lyrics.

The lyrics – which, thanks to that title and the gospel stylings of the music, call up more religious imagery than is actually explicitly included in the song – are absolutely tied to Marvin’s performance, even as on paper they’re so simplistic that they hardly seem to merit closer examination. The words here are primarily concerned with Marvin appealing to a crowd of listeners (everybody, especially you girls, usually gender-reversed when a woman sings the song): an interesting move in itself, his plea directed not just at you, and explicitly not his friends (who are mentioned separately), but rather a group of complete strangers comprising everyone else who might be listening now, or might have listened in the 48 (!!) years since this record first arrived, or who might ever listen in the future. He thinks he’s being mistreated by his girlfriend, but wants a second opinion (or rather an affirmation, since he’s made his decision already, of course); he’s asking us for a show of solidarity, for confirmation that he’s not going crazy. Some sympathy, an ego massage, and something to throw back in his girlfriend’s face the next time he feels she wrongs him. He’s seeking a situation-specific free pass, but somehow elevates the matter to something approaching a universal truth.

It’s a jumbled-up rant, mixing professions of loyalty (I believe a woman’s a man’s best friend / So I’m gonna stick by her ’til the bitter end) with downbeat imagery through little vignettes comparing his own impeccable behaviour (tossing in my sleep ‘cos I haven’t seen my baby all week) with her lack of gratitude (Is it right to be left alone / While the one you love is never home?) and even subtle come-ons aimed at those women in the crowd (I love too hard, my friends sometimes say / But I believe that a woman should be loved that way).

Perhaps this confusion is a clever depiction of a man at his wits’ end, or perhaps it’s just not a very well thought-out lyric, but either way, it puts Marvin in a place where his performance not only informs but dominates the song. He’s on spectacular form here, taking the performance tools of a rabble-rousing preacher (especially HDH’s repetitive chorus, consisting of the title delivered over and over again, call-and-response style, to a congregation of backing singers including none other than the Supremes, no less) to colour his approximation of a man who’s had enough. He’s on fire, delivering a sermon as authoritative as anything his father might have turned in, presaging his future status as high priest of sexy, sinuous music.

Perhaps this confusion is a clever depiction of a man at his wits’ end, or perhaps it’s just not a very well thought-out lyric, but either way, it puts Marvin in a place where his performance not only informs but dominates the song. He’s on spectacular form here, taking the performance tools of a rabble-rousing preacher (especially HDH’s repetitive chorus, consisting of the title delivered over and over again, call-and-response style, to a congregation of backing singers including none other than the Supremes, no less) to colour his approximation of a man who’s had enough. He’s on fire, delivering a sermon as authoritative as anything his father might have turned in, presaging his future status as high priest of sexy, sinuous music.

The band, too, know what sort of record they’re making. This is every bit as energetic as Heat Wave, if not more so; the pressure built up by the gospel flavour turns this into a full-on demand to TESTIFY! and the band lap it up, from the opening notes (a boogie-woogie/blues riff, four notes that recur right through the song, pounded out on bass and piano to within an inch of their instruments’ lives) and the waves of horns – especially tenor sax – that come blaring at the listener at the start of each line of the chorus. The liner notes to The Complete Motown Singles: Volume 3 list the players who made up the Funk Brothers on the day, research which I reproduce here solely out of respect for the musicians involved: “Marcus Belgrave and Russell Conway (trumpets), Paul Riser and Patrick Lanier (trombones), Hank Cosby (tenor saxophone), Eugene Moore (baritone saxophone), George Fowler (organ), Eddie Willis (guitar), Clarence Isabel (bass), and Benny ‘Papa Zita’ Benjamin (drums).” Note George Fowler’s presence on organ – this is the man who until recently had headed up Motown’s bona fide gospel subsidiary, Divinity Records. (It’s perhaps not surprising that the thudding, monotonous bass line isn’t one of James Jamerson’s, as it shows none of the free-flowing invention Jamerson would often sneak into Motown sessions – but Clarence Isabel deserves all the credit in the world for working so tightly with Benny to keep that unstoppable groove going.)

Those same liner notes have Lamont Dozier crediting much of the song’s musical energy to the influence of the great blues man Jimmy Reed, but I don’t really hear it here – to me, this is more about mixing elements of gospel, blues and contemporary R&B and pop to create a cohesive, irresistible whole. For all its energy, it’s never coarse, always palatable enough for the pop charts; whether that’s a dilution (either of Reed’s style or the passion of full-blooded gospel), or a refinement, is very much down to personal taste. I vote refinement; it’s not a watered-down blues or gospel number, it’s a beefed-up R&B/pop record, and a splendid one at that. Great fun to listen to, every time, and a robust dancefloor record largely immune to the passing of time – not to mention a keynote record if ever there was one for the path of Gaye’s future career (if not his life).

Those same liner notes have Lamont Dozier crediting much of the song’s musical energy to the influence of the great blues man Jimmy Reed, but I don’t really hear it here – to me, this is more about mixing elements of gospel, blues and contemporary R&B and pop to create a cohesive, irresistible whole. For all its energy, it’s never coarse, always palatable enough for the pop charts; whether that’s a dilution (either of Reed’s style or the passion of full-blooded gospel), or a refinement, is very much down to personal taste. I vote refinement; it’s not a watered-down blues or gospel number, it’s a beefed-up R&B/pop record, and a splendid one at that. Great fun to listen to, every time, and a robust dancefloor record largely immune to the passing of time – not to mention a keynote record if ever there was one for the path of Gaye’s future career (if not his life).

Something of a barrage for the senses, this is a superb single, a direct attack that works through overwhelming the defences. The best record Marvin Gaye had yet made, it surprisingly failed to meet expectations commercially – missing the R&B Top 10 and pop Top 20 – but that means nothing. This sounds every bit as good today – as vibrant and mad and alive – as it did when it first appeared, and what’s more important it’s still just as enjoyable too. Gaye’s career was now set irreversibly on the right track, such that not even Marvin himself could argue against this kind of evidence.

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in Marvin Gaye? Click for more.)

|

|

| Little Stevie Wonder “Monkey Talk” |

Marvin Gaye “I’m Crazy ‘Bout My Baby” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

I’ve been waiting eagerly for this one, and it’s well worth the wait – my only quibble would be with the grade – it’s easily a 10 for me (granted that on any such scale, Heat Wave would have to be a 15). I love what you call the ‘jumbled up rant’ – and I do think this is inherent in the song – it comes through strongly when Dusty Springfield sings it, a highly likeable, passion-stoked version, despite her inferior band. HDH seem obsessed with ‘how love’s supposed to be’ – hot blood pressure in Heat Wave, sleepless nights in Witness… Your blog will make a splendid book when it’s finished – Oxford University Press take note! In the meantime, continued fervent thanks.

LikeLike

Motown thought enough of both sides of this single to include both on Marvin’s coming “Greatest Hits” the following April as well as two different volumes of the “16 Original Big Hits”/various artists series.

Just think, by Christmas of 1963, on an automatic record changer, you could stack Heat Wave, Mickey’s Monkey, You Lost The Sweetest Boy, Witness, Leaving Here, When The Lovelight Starts Shining Through His Eyes, I Gotta Dance To Keep From Crying and Quicksand. Now that’s a party!

Marvin is not going to disappoint me now through the end of 1967 summer, and yes, I include the fantastic “Try It Baby,” and the underrated and oft-neglected “Pretty Little Baby.” All the others, he’d be in the genius hands of HDH or Smokey making records that have lost no power to entertain in all these passing decades. In fact, Marvin’s 1966 LP “Moods Of…”, much like the “Temptin’ Temptations” LP, would be very much half a “Greatest Hits” in itself.

It occurred to me the other day, that while he enjoyed quite a success streak himself in the sixties, Stevie has no major, signature hit of that decade specifically designed for him by HDH or Smokey. Wonder how that happened (or didn’t)?

Superb review again, Nixon. Nice going. 🙂

LikeLike

and the underrated and oft-neglected “Pretty Little Baby”

Not round these parts it isn’t. Watch this space…

LikeLike

I think “Can I Get A Witness” is one of the greatest Motown Records ever released. It is still my favorite Marvin Gaye record. ,” Witness” was hurt by split airplay with “I’m Crazy ‘Bout My Baby.” I always figured that because of the Top 10 Pop success of “Pride & Joy”, the similer sounding “Crazy..might have been the original “A” side. Both side entered the Billboard Hot 100 the same week (10/19/63) However “I’m Crazy’Bout My Baby” debuted @ 83 with a Star and “Witness’ entered @ 97 with no Star. In a couple of weeks “Can I Get A Witness” took off, but those early weeks of split airplay must have hurt in some major Markets.

In Los Angeles where KFWB & KRLA were the Top 40

stations ,KFWB charted only “Crazy” where it went to #7

KRLA played both sides for 2 weeks, then dropped “Crazy” and charted “Witness” for another 10 weeks into mid Jan ’64.

It could have been a bigger national hit, but as Nixon pointed out in his excellent review , it doesn’t matter now, “Can I Get A Witness” sounds as great today as it did in 1963.

.

LikeLike

You nailed it. 10/10. Probably the best record Motown ever made, and that’s saying something, and I don’t even know what Marvin’s talking about. Who cares? I found myself in a hootch in Southeast Asia in early ’64 playing this for nine other Americans…boy were they homesick!

LikeLike

Yeah, I’d go 10/10 as well. When I look at the string of his releases… it boggles my mind how good he was.

LikeLike

Yeah, this song was da jam! Wow! Love the opening piano riffs, etc. Has anyone ever heard the crazy remake from 1971 by eccentric rocker Lee Michaels? It is actually pretty cool though it sounds like a completely different song. I used to have the single.

LikeLike

Pingback: Top 5 Motown Singles: 1963 — The Curvature

Marvin Gaye is one of the best vocalists I’ve heard. This is one of my favorite songs by him, along with “I Heard it Through the Grapevine”, “It Takes Two”, “Ain’t That Peculiar”, “Too Busy Thinking About My Baby”, “I’ll Be Doggone”… I think it’s safe just to say I like Marvin Gaye’s 60s works.

LikeLike

Big surprise here. I thought Nixad would minus major points for lyrical confusion but he came through. I know it took me a long time to figure out what the hell Marvin was singing about—eventually i figured it was a minister preacher about the power of love and asking his congregation for a witness. Either way i love towards the tag fade when he finally sounds exhausted (..can i get a witness…i want a witness….) and it sounds like he is slowly fading, the choir (featuring Diana Ross) kicks in….and he’s back again (just a little bit louder). Its like a baptist service or the tail end of a james Brown concert circa 1964.

LikeLike

Ahhhh, here it is, one of the two…

Were I ever to meet somebody who asked the question “Motown, what’s that ?” my immediate reaction would be that they take some time to fully familiarise themselves with this incredible jam along with the Four Tops mighty, mighty “I Can’t Help Myself” and if they don’t “get” Motown after that they maybe never will.

Probably the best record Motown ever made Steve Robbins ? Well it’s definitely in my top 2.

One of the greatest greatest Motown records ever released Bob Harlow ? Unquestionably in my view.

I first heard this when, in 1979 as a committed Mod revivalist more interested in hearing the authentic 1960’s Mod approved sounds that the likes of Guy Stevens might have played at The Scene in Ham Yard than Secret Affair or the Merton Parkas, I bought the first volume of “Tamla Motown Presents 20 Mod Classics”. There this was, Track 1 Side 1…WOW. I took to requesting it of every DJ when I went out dancing, perfecting my steps in darkened corners of the Top Rank in Birmingham and The Swan at Yardley. Hearing this song and that album and other tracks on it by The Temptations, The Miracles and The Velvelettes clued me in to the fact that there was a Motown beyond ”Jimmy Mack” and “Third Finger Left Hand” and others that the girls at The Mackadown would dance around their handbags to, and kick started my love of American soul music and what we in the UK know as Northern Soul.

“Can I Get A Witness” is a thundering juggernaut of a record. It’s not gonna give up until it’s done what it was created to do. The Nixon Administrations “jumbled up rant” seems more to me like a stream of consciousness that Marvin needs to get off of his chest before he explodes. Every time you think “here comes the instrumental break” Marvin jumps right back in there to let us know something else that’s on his mind. That instrumental break never comes.

On reflection Steve and Bob, what the heck, one of the greatest records ever made…full stop.

LikeLike