Tags

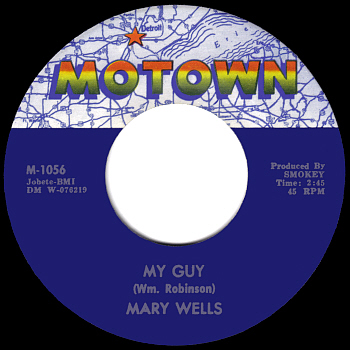

Motown M 1056 (A), March 1964

Motown M 1056 (A), March 1964

b/w Oh Little Boy (What Did You Do To Me)

(Written by Smokey Robinson)

Stateside SS 288 (A), May 1964

Stateside SS 288 (A), May 1964

b/w Oh Little Boy (What Did You Do To Me)

(Released in the UK under license through EMI / Stateside Records)

Unbelievably, this was Mary Wells’ first single in seven months, a strange circumstance for Motown’s first bona fide star. Famously, and even more unbelievably – though of course nobody knew it at the time – this was also to be Mary’s last Motown seven-inch as a solo artist.

Unbelievably, this was Mary Wells’ first single in seven months, a strange circumstance for Motown’s first bona fide star. Famously, and even more unbelievably – though of course nobody knew it at the time – this was also to be Mary’s last Motown seven-inch as a solo artist.

In between, My Guy became Motown’s biggest-selling single to date, the label’s third Number One pop hit (and Mary’s first), embarking on a lengthy spell on the charts in 1964 as spring became summer, seeping through to the popular consciousness to such an extent that even now, the best part of fifty years later, it’s hard to find anyone who doesn’t know how this goes (even if they haven’t necessarily ever actually heard it). The story of this record is one of the strangest in the Motown canon, and no matter how familiar, it still bears repeating. Pull up a chair.

Mary had been Motown’s brightest star, teaming with writer/producer Smokey Robinson to rack up a string of classic Top Ten hits (The One Who Really Loves You, You Beat Me To The Punch, Two Lovers)… in 1962. As 1963 came around, there’d been a drop-off in commercial performance, accompanied by the sense that Mary was stuck in something of a rut; the next single Smokey wrote and produced for her, Laughing Boy, didn’t show much progression from the formula, and even the remarkable follow-up Your Old Stand By failed to find much favour with audiences. Smokey had then suffered the indignity of having the Mary Wells Project opened up to outside competition, leading to what was essentially a double A-side single, pairing Smokey’s What’s Easy For Two Is So Hard For One with Holland-Dozier-Holland’s sassy contribution, You Lost The Sweetest Boy. Neither side charted particularly well (probably because both songs cannibalised each other’s airplay), and so when we come to pick up Mary Wells here, she and Smokey were – by their standards – on a considerable cold streak.

Ideas abounded on how to revive Wells’ career. New material was recorded with Smokey and with HDH, venerable standards and old Jobete catalogue numbers were dusted off for reinterpretations, an album of duets with Marvin Gaye was recorded throughout the spring of ’64, but none of this freshly-cut stuff passed muster with Quality Control as a potential hit single, and so all of it ended up back on the shelves. By the beginning of March 1964, Motown were considering trying to recoup some costs by releasing a cobbled-together LP made up of the various unreleased bits and pieces Mary had stockpiled, and Smokey was tasked with coming up with some more filler to bulk out the proposed album. And that’s how My Guy came into the world: a throwaway End Of Side One cut for a half-hearted album release.

But Smokey was often at his best when he wasn’t consciously trying to write a hit record, coming up with some of his most treasured work while, say, idly doodling on hotel stationery (as with You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me), or watching a baseball game (see I’ll Try Something New). Here, he draws on many of the raw ingredients he’d sketched out in What’s Easy For Two Is So Hard For One, trims back some of the excesses – for reasons of time, perhaps, not wanting to overburden Mary or the band with having to learn a complex structure – and out of nowhere comes up with the very best song he’d yet written. You can pretty much see the smile on Smokey’s face in the studio, as he listened to the newly-recorded track and realised what he’d done. And the next day, Mary was brought in to do her lead vocal, and ten days later My Guy was in the shops, and not long after that it was Number One.

This is just a wonderful record, on so very many levels. A pop jewel, a confection, a piece of beautiful, intricate ironwork decorated with sugar frosting, all warmed up like a delicious little pastry. Smokey and Mary had had their ups and downs, each counting on the other’s strengths at various points to ride through any momentary weaknesses, but this time they both nail it, and the effect is so astonishing that the record still works, even after all these years and all these listens.

First and foremost, it’s just a lovely song. You can read this text with cynicism (it sounds simplistic – even if you get the words right – and if the Internet is anything to go by, more than one person has apparently misheard a key line as I’m sticking to my guy like a snail to a letter), you can approach it with caustic dismissal (thanks again, Whoopi Goldberg), but it’ll always disarm you; it’s an utterly heartfelt expression of love, real love, as piercing an examination in its way as any of Smokey’s earlier lyrics or Mary’s earlier deliveries – this, this is what it’s all about, what it all boils down to. Part of that is the lyrics – Mary’s narrator coming up with great rhymes and metaphors before just completely running out new of words mid-verse:

…As a matter of opinion, I think he’s tops

My opinion is, he’s the cream of the crop

As a matter of taste, to be exact

He’s my ideal, as a matter of fact…

Some critics have completely misread these lyrics, some even (Terry Wilson, I’m looking in your direction) going as far as to suggest Mary “may have misread the lyric sheet”, which is just ridiculous. No, this is Smokey the lyricist at the top of his game, not only working out the phrasing of the words to precisely fit Mary’s diction (as was his particular speciality), but now making form reflect meaning, having Mary’s character use intentionally repetitive wording to reflect a lovestruck but clear-eyed sentiment: my man is the best, and that’s all there is to it; there’s no other way to put it. It’s joyous, in a way so few pop records are – a sincere, uncomplicated kind of joy.

It’s just a lovely record, isn’t it? For which, I suppose, we really have to thank Mary, Smokey and the band, pretty much in equal measure.

To Mary first, because this is her crowning achievement, the one record she’s forever to be remembered for. She’s magnificent here. Supposedly, she screamed herself hoarse before the final take captured here, in order to give her voice a slightly roughened effect (shades of her début, Bye Bye Baby). Whatever the case, it worked. Her voice has literally never sounded better; there’s a tangible sweetness of character, undeprinned by a breathy, throaty hint of sexuality, culminating in the final, spoken, almost-whispered lines, There ain’t a man today / Who can keep me away from my guy, Mary smouldering so intensely she’s barely even breathing the words; the single greatest line delivery in the entire history of pop music.

I’ve talked about her underappreciated skills as an actress before, but this is on some whole new level. A song about love and faithful devotion is riven with potential pitfalls for a vocalist (get the tone wrong and the whole thing collapses), and this is a difficult song to sing without slathering everything in treacle and coming over too simplistic (see above re: Whoopi Goldberg), but Mary gets it just right. She’s never smug, never boasting, never threatening, but equally she’s no simpering anti-feminist; she’s just really, really in love, and it’s a perfectly-judged performance. No single man could listen and not be swept away, jealous of Her Guy, and no single woman could listen and not wish fervently to have what Mary seemed to have, but it was also a perfect record to express the devotion of true love to insecure boyfriends; My Guy has something for everyone. Men fell in love with her, women wanted to be her (or, at least, she was saying what they’d like to have said in the way they’d like to have said it), million-selling Number One pop record dominates summer. Easy.

Smokey’s turn now. He obviously took note of what Holland-Dozier-Holland had been up to, and he looked at what had and hadn’t worked in his own songs recently (especially the Temptations’ breakthrough The Way You Do The Things You Do), and set about constructing a groove, a Motown groove through and through. Without even realising it, everything he’d learned up to now had been building to this; ironic that it should take a routine paycheck commission to unlock the pattern and finish the puzzle.

Like another deceptively simple-sounding Motown hit, the Marvelettes’ Please Mr Postman, there’s actually a lot of clever stuff happening under the hood here that goes unnoticed by the listener because we’re so utterly swept along by the effects they create. A great horn riff before each two-tone hook, to keep the momentum going all the time despite the time signature and Mary’s delivery which make the song more sedate and stop-start in the memory than the non-stop hustle it really is. There’s no dead air whatsoever – the natural gaps in the song are filled in with piano, handclaps (for that group atmosphere – this is no quiet, private confessional, it’s an inclusive song in which Mary is telling the world loud and proud about how much she loves her man, so it’s only natural the record sounds like a party where everyone’s equally happy for her), and some great backing vocals from the as-ever uncredited Andantes. And just in case the galloping, irresistible rhythm gets close to being too dull or predictable (the bane of many a cover version without the benefit of the amazing Funk Brothers playing the instruments), Smokey is also smart enough to throw in those blaring, momentarily disorientating trumpet fills, quietly unsettling but just quiet enough not to disrupt proceedings, which keep everything interesting.

The band are the real unsung heroes here, turning in one of the all-time great Motown performances (all the more remarkable since they apparently cut the track at the end of a very long day working on cuts destined for The Temptations Sing Smokey). The intro, derived unashamedly from Hugo Winterhalter’s 1956 rendition of Eddie Heywood’s Canadian Sunset, was apparently their idea, but there’s all manner of great work going almost unnoticed underneath Mary’s fireworks and the chugging rhythm. Just listen to that bass! Take a bow, James Jamerson. Listen to the piano glisses! Bravo, Earl Van Dyke. The stinging guitar figures! Chapeau, Eddie Willis and Robert White. If just one of the Funk Brothers drops the ball here, then everything grinds to a halt, but everyone involved is willing this to be good, no matter how tired they are or how unpromising the project must have seemed to begin with.

On release, this climbed the charts with ease, coming to dominate the airwaves in most markets (though some DJs preferred to play the B-side instead, of which more in a couple of days’ time!), and it hit Number One ready for the start of summer, a long summer in which My Guy just kept selling, and selling, and selling. In Britain, where My Guy was licensed to Stateside Records, it became the first Motown release to make a serious dent in the UK charts, reaching the dizzy heights of number five and catching the notice of the Beatles, who declared Wells their favourite American singer and invited her to open for them on their British tour during the summer of ’64.

On release, this climbed the charts with ease, coming to dominate the airwaves in most markets (though some DJs preferred to play the B-side instead, of which more in a couple of days’ time!), and it hit Number One ready for the start of summer, a long summer in which My Guy just kept selling, and selling, and selling. In Britain, where My Guy was licensed to Stateside Records, it became the first Motown release to make a serious dent in the UK charts, reaching the dizzy heights of number five and catching the notice of the Beatles, who declared Wells their favourite American singer and invited her to open for them on their British tour during the summer of ’64.

Anecdotes abound regarding the record’s runaway success; Motown apparently had to press up more stock to refill the racks of stores that had completely sold out, only to receive frantic calls from the distributors the same day asking for yet more copies. The money began pouring in left, right and centre. Motown had had big hits before, even Number Ones, but this was different; this was a sensation, a shift in the balance of power.

It was still a commercial rather than cultural shift, but the one would lead to the other, as Motown ploughed the profits from My Guy into upcoming releases from its ever-improving, suddenly-hot star acts – the Temptations, Marvin Gaye, Martha and the Vandellas, newcomers like the Four Tops and the Supremes.

This last point proved to be a real bone of contention, and was supposedly a deciding factor in one of the most astonishing developments in the Motown Story: Mary Wells, just 21, at the top of the charts, the world at her feet, walked out on Motown while My Guy was still flying off the shelves, and more or less ended own her career.

It’s gone down in history as one of the all-time Dumb Moves, though the story is still distinctly murky, and how much is fact, and how much is fiction (and how much is flat-out paranoid delusional stuff) remains hotly debated even now. The raw facts, on the face of it, are these.

Mary had signed to Motown, first as a writer and then as an artist, when she was just seventeen. She’d married young – her husband was dancer, bandleader and sometime Motown recording artist Herman Griffin, a volatile egomaniac by all accounts (few of them firsthand, it must be said) who promptly installed himself as Mary’s de facto manager, chaperone and stage conductor. Known for trying to upstage Mary during stage shows by doing backflips and splits, and for carrying a loaded pistol into business meetings (at least one of which ended with someone actually getting shot), Griffin and Wells endured a torrid, turbulent relationship, and according to many sources they were already divorced by 1964, but he still remained as a major influence in Mary’s life.

Before My Guy came along, when Mary was struggling for hits, Griffin had supposedly begun to investigate the possibility of extracting Mary from her Motown contract, but the price was too high and Motown were unwilling to lose their investment. When Mary’s ship unexpectedly came in, it didn’t take long for several of her hangers-on (including Griffin himself) to start openly asking why Motown didn’t seem to be investing the profits from My Guy back into Mary’s career, instead spending the money on other acts, most noticeably the Supremes, who’d never had any real success and whose lead singer was the subject of widespread rumours regarding her relationship with Motown boss Berry Gordy. They also asked why, now that Mary was a genuine international chart-topping superstar, was she still on the paltry royalty rate she’d signed up to as a callow teen? Surely she deserved more?

Here’s where it gets messy. By some accounts, Mary approached Motown for a better deal, and was politely told to go away and do as she was told. Motown, for their part, insist they had big plans for Mary’s future career, big money lined up to push her future releases, big songs in the pipeline for her to sing; when she turned 21, Berry Gordy threw a party and presented her with five thousand dollars’ worth of clothes and jewellery. She was going to be the face of Motown for years to come.

In June of 1964, Mary announced she was leaving Motown. Since she’d technically been a minor when she originally joined the company, and since she’d not had proper representation, the contract she had signed was, she declared, null and void. Furious, Motown first issued statements to the press and took out adverts saying Mary was going nowhere. When Mary went public with her walkout, Motown went nuclear, spent several months and thousands of dollars suing her for breach of contract – and lost. Berry Gordy, who didn’t take kindly to public humiliation, must have had steam coming out of his ears at this point.

Mary became the most hotly-pursued free agent in pop history, finding herself at the centre of a massive bidding war which was eventually won by Twentieth Century Fox. The deciding factor was the promise of a film career, a promise apparently – going by the later comments of Fox executives – made in complete bad faith as a ruse to get Mary to sign. She would in fact never make a film, and she would never have another Top Ten hit record.

Bad advice meant Mary’s move to Fox, a dream move on the outside, turned into a nightmare. In exchange for a then-astronomical signing fee of two hundred thousand dollars, Mary was persuaded to accept Motown’s comparatively reasonable-seeming conditions as part of the settlement. She would take a nominal payment in exchange for forgoing any future royalties from her Motown recordings (the contract governing which had, after all, been declared illegal). Egged on by Griffin, she proceeded to burn her bridges with Motown in the most public way possible.

This was a foolish move; the dark but completely unsubstantiated rumours that Motown directly intervened to squash her future career by putting pressure on DJs and distributors have never quite gone away, but even if there was no direct action on Motown’s part, there was a very clearly defined stance of “us and them” between Motown and Mary Wells; you either aligned yourself with one or the other. Wells had had one big hit, Fox had the money, but Motown had the songs and the talent, and there was only ever going to be one winner.

When Mary finally got back into the studio towards the end of 1964 to resume her career, she immediately went down for several months with TB before knocking out a couple of singles – some of them quite good, but not great, and certainly nothing approaching her Motown best – and a distinctly underwhelming LP of Beatles covers. She left Fox in 1966 and decamped to Atco, but there were to be no more big hits. She moved to Jubilee in 1968, then to Reprise, with ever diminishing returns. By the end of the Sixties, she was without a record deal, a forgotten footnote; sporadic revivals amounted to little success before her untimely death in 1992.

All of which is both tremendously depressing, and very much at odds with the glorious joy that is My Guy. Perhaps it was always unfair to expect Mary to do anything like this record again; it sets the bar impossibly high, and while her commercial fortunes may have waned dramatically after leaving Motown, to her credit she seems to have been justifiably proud of having made this masterpiece rather than destroying herself over the years trying to match it.

Ultimately, the career of Mary Wells is best remembered by listening to My Guy. Play it loud, and remind yourself how incredible it all is, what a wonderful single. The band are brilliant, Mary is brilliant, and the exceedingly well-crafted lyrics mean that everyone’s efforts are in the service of a beautiful, wholly lovely pop record. And for that, not for historical significance or critical representation, it gets a ten from me, probably the easiest one I’ve ever had the pleasure to give out. Perfect.

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in Mary Wells? Click for more.)

|

|

| Liz Lands “Keep Me” |

Mary Wells “Oh Little Boy (What Did You Do To Me)” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

Didn’t Berry Gordy’s soon-to-be ex-wife Raynoma bootleg copies of this??

LikeLike

So the story goes, yes. I’d direct you to Robb Klein’s comments on the articles for Sammy Turner’s Only You and the Serenaders’ If Your Heart Says Yes, where he covers this stuff quite comprehensively.

If it’s true (and I’ve no reason to doubt it!), it just goes to illustrate what a big deal this record really was commercially; hard to imagine that happening with, say, Fingertips.

LikeLike

LMAO! Wow that was shady.

LikeLike

Great analysis of this timeless and beautiful classic. I too loved the song but never really looked at it the way you do and have in this review. But… I must correct you on the lyrics..” I ‘m sticking to my guy like a STAMP to a letter” not snail, sorry !

LikeLike

That was meant to be a deliberate misquote – does it not come across? I’ll change the wording a bit.

LikeLike

Wonderful job of summing up this great record and the amazing story behind it. I had to listen to it again and was reminded how fresh it always sounds (and how pale all cover versions sound by comparison).

LikeLike

Agree! I’m 22 and this song sounds just as fresh as anything that’s out today.

LikeLike

My kid brother was busy getting himself born the two weeks this was at the top of Billboard. Me (newly 10) and my sister ( 11 1/2) stayed with my mom’s brother and his second wife the week Mom was in the maternity ward.

Uncle Joe and Joanne spoiled us rotten, driving us to and from school every single day, even though my sister and I knew our way about buses and elevated trains, there in Philadelphia. During every car ride, we were hearing either “My Guy” or the Dixie Cups’ “Chapel Of Love” (quite a perfect record itself).

Thus, “My Guy” does not remind me of any romance, but a hell of a great “guy” nevertheless, my kid brother, now 47. (Ultimately, the wonderful girl he’d marry was born the week another Motown record was at No. 1: “Stop! In The Name Of Love”.)

Sometime many entries ago, Nixon, I said didn’t envy you the work of coming up with fresh superlatives for Motown’s perfect singles, and I know this one had to be a very difficult task. You did a marvelous job, you really did, and with the breakthrough smashes of The Supremes and the Four Tops, and the monument of “Dancing In The Street” within months, we hope you’re getting plenty of rest and the right brain food.

🙂

LikeLike

This was the record that did much to split the UK R&B scene into two distinct camps, old wave and new. So sweet , so annoyingly commercial, so NICE, it was never going to appeal to the Howling Wolf or Muddy Waters fans.

LikeLike

It’s tempting to brush that off with a glib response along the lines of “More fool them, then!”, but I think it’s something that warrants further consideration. Motown were often accused of “selling out” in the mid-Sixties with their wholesale shift into pop music, but for me – if we’re going to use labels at all – they were always more of a pop label to begin with, just a different definition of pop than might have been accepted in 1962. People in the US accused Berry Gordy of abandoning his core black audience, forgetting that he went into business to sell lots of records, not to be a beacon of African-American advancement. (I rambled on about this at some length back when discussing Sammy Ward’s Someday Pretty Baby, if anyone remembers.)

In the UK, these issues always feel more the preserve of the poseur or the “serious” collector, part of that peculiar British trait that mixes up snobbery and shame when talking about popular music. There’s a streak of this in the Northern Soul movement, but it really stalks all areas of British musical appreciation: it’s got to be authentic – if it’s too fun, or if it sells too many copies, or if too many uncool people enjoy it (kids, young teens, housewives, people who only buy one album a year, hipsters, scenesters, hippies, chavs, students, senior citizens, or whoever else is under the cosh that week), then it’s got to go. Can’t be seen endorsing something in the Top Ten, no no no no. At least not the current Top Ten.

Which is fine, if that’s what floats someone’s boat, but I’ve just never understood how anyone manages it – there are just too many amazing records out there, it makes no sense to me to artificially limit oneself by closing off whole areas. I’d like to think anyone’s record collection (and anyone’s life, come to that!) has plenty of room for both Howlin’ Wolf and Mary Wells, and if they decide otherwise, well, no skin off my nose, but it’s really them who are missing out. 🙂

LikeLike

I’m sure there were some so-called fans who wanted Motown to remain their own personal preserve, and when it became too successful for them moved on to something more esoteric. Personally I wanted it to appeal to as many people as possible and tried to spread the word with an almost missionary zeal.

LikeLike

Peaked at Number 5 in the U.K. Record Mirror Chart – that’s the chart used subsequently in the ‘Guinness Book Of British Hit Singles’ published and updated (almost) annually from the mid-70’s onwards, and oft-referred to nowadays as the “Official” U.K. Chart – BUT – back in the day, in the 1960s, the MOST INFLUENTIAL U.K. CHART was that published by the NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS – no doubt in my mind about it, having lived through the 1960s as if glued to the Charts – where “My Guy” peaked at… NUMBER THREE.

LikeLike

Ah, yes – I should probably clarify this now, really, as wars have been fought over this issue! When I talk about the US charts, I’m talking about the Billboard rather than Cash Box charts; similarly, when I talk about the UK charts, it’s the Record Retailer chart I mean.

One of the many blogs which inspired me to start this whole project is Tom Ewing’s Popular, a blog discussing every UK number one, and they obviously had the same discussions, at great length, regarding the NME chart – especially concerning the Beatles’ Please Please Me, which was a number one on pretty much every British chart except the “canon” official one, but which therefore doesn’t qualify for inclusion on that blog. The conclusion was that while the NME chart (and some other “independent” charts) were far more widely known than the Record Retailer version, as the de facto trade journal the RR chart’s methodology and sample size were as valid in 1962 as in 1982. You have to set rules; my rules are the data used by the modern-day Official UK Chart Company, the successor of that old Record Retailer chart (and thus tallying with the likes of Everyhit, Music Week, and of course The Complete Motown Singles series), even if for most of the Sixties, that won’t have been the chart most readers remember seeing at the time.

LikeLike

Aha, yes… I’ve heard of this “war” 🙂

…and here I’m suggesting that “My Guy” was likely a bigger U.K. hit single, than the so-called “Official” Chart would have us all believe.

Some other info of interest – from the U.S. CashBox Top 100:

– Chart Entry date week ending October 31, 1964, at the #89 position – “Ain’t It The Truth” – Mary Wells (20th Century-Fox 544)

LikeLike

Oh, I think that’s completely valid – I just wanted to explain why I’d said five and not three.

Huh, rather embarrassingly, I didn’t actually know Ain’t It The Truth came out that early – I thought her Fox début was Use Your Head in 1965, and that Ain’t It The Truth came later. I’ll amend the chronology in the article a bit (I’ll be talking about her Fox, Atco etc. career more in future entries), but my initial reaction: what a strange, strange choice for a comeback single!

LikeLike

WOW, that shows how dumb I am , I thought Mary’s FOX debut was ” Never Never Leave me “. When did that song debut because I thought it was beautiful and use your head was a hit in my Brooklyn neighborhood

LikeLike

Excellent analysis, Mr. Nixon! A perfect mark for a more than perfect recording. There have been, of course, many other artists who have taken a stab at this song but have failed to capture its magic (even the Supremes could do it no justice; Florence Ballard, on lead, might have pulled it off). There is one rendition, however, which comes close and that is Aretha Franklin’s. This originally appeared on the album “Runnin’ Out Of Fools” in 1964. It’s somewhat jazzier than Mary’s version but swings along nicely aided by a pretty fine-sounding contingent of backing singers. Like many, I was shocked that Mary left Motown right after this became a smash but was thrilled when she showed up again on the charts later in the year with “Ain’t It The Truth” on 20th Century-Fox.

LikeLike

Ooh, interesting! I’d not actually heard her version before.

Reaction (having listened to Mary’s version about a hundred times over the last few days)? Well, let’s face it, Aretha isn’t very likely to balls anything up, though I don’t like her phrasing here (that could just be overexposure to the original) and it’s probably the most capable cover I’ve ever heard – but it strikes me as kind of pointless, really.

LikeLike

I’ll agree that this isn’t Aretha’s best work. She sounds more like Teresa Brewer than she sounds like herself (no offense to Ms. Brewer; I enjoy her work).

LikeLike

This may be the first Aretha track I didn’t love – she had no trouble taking Otis Redding’s Respect and making it hers, but she’s definitely over-swinging the phrasing – weird.

LikeLike

Have you ever heard Diana Ross and The Supremes “My Guy, My Girl” ?It comes from their ’69 album Together. The Supremes add a little funk “My Guy”

LikeLike

Yeh I heard that. It is kind of fun. Amazing. At least 4/5 of the Tempts can say they recorded the same song twice. By this time, as I am sure you know, David Ruffin had been replaced by Dennis Edwards.

Can you believe there are people out there who still think the Supremes recorded “My Guy”? Of course, many people think the Shirelles & Aretha Franklin are “Motown” artists. Oh well. My buddies are amazed at how little I know about sports!

LikeLike

Yeah I always have to look at people sideways when they state incorrect facts about Motown. Most people also think that the Four Tops sung “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie)” or that the Supremes ended when Miss Ross left. Sometmes I get sooo mad…but then I have to remember everyone is not a Motown Junkie like me lol.

So true I never thought about the Tempts recording the same song twice lol. I like both David & Dennis as lead they had similar yet very different swag.

LikeLike

Griffin and Wells were divorced in ’63. That he was still influential in her life after that is hearsay and isn’t necessarily substantiated.

“My Guy” is a great song and absolutely deserves a 10/10

LikeLike

Hmm – I bought “Ain’t It The Truth” (moody, brooding – and loved it) but… confusingly for most folks, was also released on Stateside in the U.K.

LikeLike

Whether or not Herman Griffin still had any effect on Mary’s decisions by mid 1964 is a moot point. He certainly tried to become her manager again at that time. He had had already put the idea into her head that she had been taken advantage by Motown when she signed the original contract, and she was not going to change her mind about that. When Motown decided to not tear up her old contract, and write a new one giving her compensation commensurate with her new star status, she was going to leave in any case.

LikeLike

There was such good stuff remaining ‘in the can’ too, as the My Guy album (“Does He Love Me,” “He’s The One I Love”), Vintage Stock album (“One Block From Heaven”(!), “When I’m Gone”) and Looking Back CD set ( those songs, plus “My Heart Is Like A Clock”) all prove.

It’s testimony to Gordy’s anger that he never allowed any of these terrific songs out as 45s lest they improve Mary’s stock at some other record company.

While we mourn that we’ll hear from her no more from this point on a Motown single again, we should acknowledge, though, another distinct possibility.

After the five Billboard No. 1’s in a row by The Supremes, Mary Wilson, Florence Ballard, Martha Reeves, Gladys Horton, Wanda Young, Brenda Holloway, Kim Weston, Gladys Knight, and every other female at Motown stood in line behind you-know-who. Had the progeny that followed “My Guy” by Wells not returned similar tonnage, she too might have found herself in that large shadow cast by Ross. With plenty of sisterly company, yes, but still in the shadow.

We’ll never know for sure.

LikeLike

We still have a lot more reviews to come on Miss Wells, though – her next two singles were already recorded, selected and lined up with catalogue numbers when she quit unexpectedly, so they’re included in the Motown canon, in TCMS 4 and therefore in the remit of Motown Junkies. Plus, there’s her duet with Marvin Gaye, and (of course) the B-side to this one… that makes seven more Mary Wells reviews yet, even though we’re effectively saying goodbye today.

Point is, there’s a lot more ground yet to be covered, a lot more theories and ideas to be explored – stay tuned 🙂

LikeLike

In Los Angeles from Jan 18th through April 24 of 1964, the number one records on KRLA’s Top 40 chart were all by The Beatles.

“My Guy” was the record that knocked the Beatles off the top of KRLA’s Survey. It jumped from # 9 to #1 where it stayed for 5 weeks, followed by 4 more weeks at #2. The biggest Motown hit in LA to date.

The KRLA List of the top hits for 1964 had “My Guy” ranked at number 2 for the year behind “I Want To Hold Your Hand”

LikeLike

ONe has to understand that during 1964, there was no Billboard R & B chart. Mary had to contend with the Jersey Boys, The Mersey Boys, and the Beach Boys—not to mention New Orleans trumpet players, Texas teenabillies, —and groups once known as The Primes and Primettes!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

LikeLike

Did anyone see the recent episode of Usung about Mary Wells? It was quite good though they said nothing about her duets with Marvin Gaye. I didn’t realize she had a comeback dance hit in the early 80s with Gigilo. FYI I survived the East Coast earthquake yesterday. Office shook for a few seconds but that was all.

LikeLike

An outstanding review of an an outstanding song (and a very depressing story!)

Thanks so much.

LikeLike

Just took your advice and listened to all my versions of this song, including all the similar 2:50-ish versions, the 3:05 version from the Motown Box, the Motown Original Artist Karaoke versions (listening to just the band, and then just Mary), and a truly horrifying disco-ized version (incredibly sad because the band sucks, but you can still appreciate the beauty of Mary’s voice).

LikeLike

In the opening beginning of “My Guy” are those horns muted trumpets mixed with trombones or what? It sounds like the World War II Carter-Gents air raid warning siren. Too see what I am talking about go to You Tube, and punch in Carter-Gents or Gents-Carter air raid siren when Germans were dropping bombs on London. Better known as the London Blitz. I still love the song to this day. That opening always caught my ear which is a very good hook line, it’s repeated again about almost to the end of the song

LikeLike

“my guy” seems a little too obvious to give a “10”! i had led myself to believe your ratings might be wildly exciting! i’ll keep on holding on to see if your tens tread off the classic radio hits. i have a few i am waiting for you to get to a few of my faves just to see how you rate them … don’t get me wrong. i love your site and am disappointed when you take a few days off! keep up the fantastic work, chap!

LikeLike

i was expecting wilder ratings, especially when it came to “tens”. “my guy” seems too obvious considering the wealth of wells’ oeuvre at motown. hope you will not be handing them out willy nilly to the few hits that the oldies station have on continual rotatation! i am anxiously waiting for a few of my favorites that don’t get played with any regularity except in my own home! don’t wanna give any clues (except perhaps to say i am curious how “7 rooms of gloom” does! … don’t take my critique wrong … i check everyday hoping for a new post! this is quite a project you have taken on and immensely more interesting that the notes in “the complete motown singles ” set! keep up the grand work, chap,

LikeLike

Thanks for your comments!

Re: 10s – it’s something I’ve given a lot of thought to, that’s for sure. On the one hand, I don’t want to be handing 10s out like confetti (or, more accurately, like “long service” medals). On the other hand, I’m not going to pull up short of giving a great, classic Motown record top marks just to be an iconoclast. It was that that stopped me giving out any marks at all for the first, ooh, year or so of this blog’s existence (all the marks before about 180-ish were added retrospectively). As a compromise, I thought about “Motown 50”, the recent compilation CD, and asked myself what my own fifty favourite Motown tracks would be – and having agonised for weeks and weeks over that playlist, swapping things out, putting things back, listening to it everywhere I went, those fifty favourite tunes became my fifty 10s. And that’s how many there’ll be when this is finished: exactly fifty.

Now, some of those might seem like crushingly obvious choices – so far, I’d contend only “My Guy”, “Please Mr Postman” and possibly “Heat Wave” fall into that category, but I know there are some really obvious ones looming on the horizon. (But, hey, what can one do? There’s a reason a lot of these oft-played classics became oft-played classics, and I’m not going to pretend otherwise just to look cool.) On the other hand, I’ve also awarded top marks to the likes of the Supremes’ I Want A Guy, the Temptations’ Dream Come True, the Marvelettes’ Strange I Know and the B-side here, Oh Little Boy, and I’d wager very few people had those written down beforehand. I also pointedly didn’t give tens to the likes of Money, Shop Around, You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me or The Way You Do The Things You Do, and I won’t be giving them to several others coming up that some people would doubtless consider automatic choices. (Mentioning no titles yet, as I don’t like to spoil the surprise!) I’m also fairly confident not many people saw me pulling out 9s for the likes of Pilgrim Of Sorrow or May What He Lived For Live or, in Mary’s case, Strange Love, for example.

The point is, the tens are my top fifty, my own personal favourites; some are obvious oldies radio fodder mega-hits, and some are obscure B-sides or cuts from long-forgotten acts (and in one case, both). Hopefully you’ll be intrigued by a few of my picks, even if you roll your eyes at some others – but rest assured, they’re all there solely because I love the record in question. And it’s just my opinion – as always, people are free to disagree as much as they like and post their own opinions on every page – dissent is encouraged!

(And there have only been nine so far, out of 434 reviews – if anyone wants to play “Motown Junkies 10/10 Bingo” by trying to identify the remaining 10s ahead of time, please feel free!)

LikeLike

I suspect you’re not very happy with today’s mark either…!

LikeLike

Mary told me that Sam Cook was the first to tell her she was not being properly compensated by Motown.Motown did not promote the Supremes until Mary was gone.Barney Ales took out an ad in Billboard which was like a warning to to other labels that Mary was still under contract to Motown BUT that they would have a new #1 record WDOLG by the Supremes. Motown then proceeded to tie Mary up in Court for several months before 20th could release her first record(October) & she was in England touring with the Beatles, not here to promote her first 20th release.The time lapse was detrimental & her career never recovered.Barney Ales could also give the big record distributors an option of carrying the 20th Century line or the Motown line.

LikeLike

Gee, Nixon this is a long post, but a great one = ). I can not recall the first time I heard ‘My Guy’ but I know this song! Btw Nixon adore your humour about Whoopi lol I never dug that ‘Sister Act’ version myself. I didn’t realize this was her last record with Motown. This really showcases how brief her career was. I wonder if she would have done what Diana Ross and The Supremes did had she stayed on Motown.

Like you mentioned above this is a sincerely joyous pop record and I have always loved her end bit “It’s not a man today, who can take me away” as youngsters like myself say that was dope lol. I think The Marvelettes “deliver de letter de sooner de better” runs a second close.

On Wells, I saw this tv program called Unsung about her last year. It was a bio. I never realized how young she was when she made this song. Her story somewhat reminds me of Flo Ballad’s with men influencing their decisions to leave Motown. I know Berry and his Motown staff had alot of shady ways, but I wonder if Mary & Flo realized that they were at the cream of the top at that time and no other record company would cater to them like Motown did. Even Miss Ross found that out in the 80s when she left Motown.

Quick question did Mary appear on Motown 25?????

LikeLike

Hi! I’ve been away for awhile. In answer to your question, Mary Wells did appear on Motown but it was very brief. She sang a few bars of “My Guy” and that was it. The same thing happened with Jr Walker (Shotgun) & Martha Reeves (Heat Wave).

I also saw the Unsung episode. Thought it was very good but very sad.

All the best to you.

LikeLike

Thanx Landini!

LikeLike

You are very welcome. I am enjoying your comments. It is so refreshing to hear a “young person” appreciating Motown so much. By the way, there was a very good Unsung about Tammi Terrell. Again, very sad but very informative. You might find it on YouTube.

LikeLike

Thank you! I hoped I wasn’t getting on anyone’s nerves posting almost everyday lol. This blog is like having a birthday everyday to me. It’s very special and such a treat for me because I have never heard more than half of these songs. As an aspiring singer/songwriter I learned to sing & write songs by listening to a greatest hits of Motown CD when I was a kid that my parents had. Even back then I recognized that there was something unique about the Motown sound. Alot of my friends tell me that I have an old sold because I like to listen to “old music” as they say, but I just tell them I like good music which is ageless. Nixon ‘s critiques and everyone’s feedback is so insightful and delightful for me to read.

I did catch that Unsung about Tammi when it first aired and it is was very sad. One of the best I’ve seen! She had a great voice and it seemed a good spirit. I was so intrigued by her after it aired I bought the book that her sister wrote. The book is okay, but kind of sketchy which is understandable.

LikeLike

Hi, You might enjoy a book by Sharon Davis on Motown. She goes into depth about the music (much like our friend Mr. Nixon) & includes an exhaustive discography. You might find it in your local library. She avoids going into the tabloid details of the artists’ lives which I think mars so many Motown books. Of course, I grieve for the trouble many went through but rehashing the stories in sensationalist style doesn’t help anyone.

Back to Tammi for a minute. Maybe if it was today & she had gotten her brain tumor she might have survived. I know there have been so many advancements in medicine. A lady at my church has had 2 major brain surgeries over the last 8 years & is doing great. On a personal note, I’m a cancer survivor myself, so I especially grieve Tammi’s loss – feeling like I’ve lost a fellow soldier on the battlefield. Oops! Sorry to get so morbid.

Anyway, keep up your comments. You seem like a very intelligent, insightful young woman. Best of luck to you with your music as well.

LikeLike

Thanx Landini and congratulations on being a survivor! I agree if Tammi were diagnosed today I think she would have been saved. Her story is also similar to Jean Harlow’s dying young of an illness that can be treated for in today’s world. I heard many say that they think that James Brown & David Ruffin hitting her on head had alot to do with her developing the tumor. I don’t know what to think about that.

I’m going to have to see if I can a copy of this Sharon Davis book you mentioned above. You are correct most book on Motown do sensationalize the drama and of course I can see why, but it’s always great just to talk about the movie. It’s funny I was just recently watching my Lady Sings the Blues dvd and there’s an interview featured where Miss Ross talks about how she is hurt that former Motown artist don’t give Berry the respect he is do. To some extent I agree with her, but there was a lot of tragedy that took place at Motown so I can understand why some people still hold grudges against Berry til this day.

LikeLike

This song is sooooo dope that I had to do a quick cover between classes. Of course I’m not as good as Mary, but this is just my way of showing respect = )

LikeLike

The Diana Ross influence is obvious. Looks good on ya!

LikeLike

Thanx = )

LikeLike

You have a nice voice. Keep singing! I’ve messed around with singing most of my life. I’ve sung in choirs & stuff on & off. Did a few solos here & there. I wrote some songs in college & performed them in small settings. That was ages ago! I had some major surgery in May 2010 (which saved my life!) but it has affected my diaphragm a bit so singing can be a little hard these days but I still enjoy it.

Your comments & insight have been a real blessing to us here!

LikeLike

Aw thanx! I find that singing & writing are the best therapy lol. If you don’t mind me asking what kind of music did you perform back in the day??? = )

LikeLike

Hi Again. I wrote some Christian pop songs & sang them by accompanying myself on piano. I performed them at some Coffehouses our Christian Fellowship Group at college used to put on. I didn’t really know enough music theory or (piano for that matter) to go real far with songwriting. I wanted my songs to sound like Motown/Beatles. Most of them sounded more like Easy Listening (LOL!) A friend of mine (who had less muscial experience than I) & I had this idea of writing a musical based on the book of Acts, but we didn’t get past one song! Oh well! This all happened back around 1977-80.

LikeLike

Wow that is sooooo cool. There’s nothing wrong with Easy Listening lol. Olivia Newton-John is my 3rd favorite singer and before her “Totally Hot” album she was Easy Listening mixed with a little country lol. You and your friend where onto something with the musical based on the books of Acts too bad you didn’t start = ). Do you still write now?

LikeLike

My goodness. You sure have some eclectic tastes in music! Never really cared for ON-J but I should probably check her out again. I did like her song “Sam”. Really pretty. Actually I liked singing along with “Let Me Be There” & doing the guy’s bass vocal part!

No, I haven’t written anything in years.

LikeLike

LOL you’re not the first person to tell me I have eclectic taste in music. I personally think ONJ is so underrated in the vocal department like Miss Ross. I’m also a huge fan of her now cult classic film Xanadu. It had such a great soundtrack with ONJ mixed with ELO. You should most definitely revisit her catalog. Her pop span from 78-88 is my favorite era of hers, but the earlier stuff really showcases her beautiful and at times angelic voice. Yeah let me be there is a fun song to sing along to.

Michael Jackson is my all-time favorite then Diana Ross. Other favorites of mines Kylie Minogue, Blondie, Dolly Parton, ABBA, The Shangri-Las, Dusty Springfield, Barbara Mandrell, Loretta Lynn, Culture Club, Madonna, Tina Turner, the modern tina- Beyonce lol, Sylvia Robinson, The Jackson 5 (including their music as The Jacksons), The Supremes, Prince, Vanity 6, Barbra Streisand, Cher, Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, Pat Benatar, 60s Temptations, Donna Summer, Phyllis Hyman, The Ronnettes, newly added to my list thanx to Nixon The Marvelettes, I can even get down with The Andrew Sisters lol.

Yeah I’m pretty everywhere with my musical taste. lol.

LikeLike

The perfect pop record! Anyone living back then can tell you how often we had to hear this song and no one ever once complained! Mary must have done every TV show known to man behind this record. I specifically remember her on “Where The Action Is” and “Shindig”

LikeLike

Actually when she was on Shindig (I remember seeing her too) and Action (don’t remember that one but it was on in the afternoon where I lived) she was past pushing My Guy and gone from Motown. Shindig premiered in the fall of 64 and Action came on the following summer. So she was probably pushing her 20th Century stuff and reminding people (with short memories) that she was the one who did My Guy.

LikeLike

“Where The Action Is” was good for that. I saw the 5 Stairsteps on that show doing “You Waited Too Long” and it had been a year old. I think the standard at that time was to perform your latest release as well as the single you were known for.

LikeLike

IIRC Where The Action Is had James Brown on A LOT (not complaining) and he would do songs from all periods of his repertoire, which was considerable by 1965-66.

LikeLike

I remember seeing him there a few times as well as Otis Redding and The Kingsmen!

LikeLike

this video clip was posted recently of Mary doing her hit on the Steve Allen Show live.The only thing missing is Jackie, Marlene, and Louvain.

LikeLike

According to the sleeve notes on a French import lp I bought in the spring of ’66, playing piano on this was Johnny Griffith, the full credits are shown as:

Herb Williams, John Wilson (trumpet); George Bohannon, Paul Riser (trombone); Earl Van Dyke (organ); Johnny Griffith (piano); Dave Hamilton (vibraphone); Robert White, Eddie Willis (guitar); James Jamerson (bass); Bill Benjamin (drums); 3 un-named backing singers – Detroit 2nd March 1964

LikeLike

What is never mentioned and discussed is the lack of Education and Business wisdom Wells never had, or for that matter, none of the other Motown Stars, either.

It takes brains to see things as they are and to understand what is going on? Wells listened to her, then, husband who helped talk her out of her Motown Contract and who told Wells that she was being exploited by Motown.

Wells never had the guidance to know what to do and how to do it. Hence, she paid the price and disappeared.

Even Dian Ross left Motown in 1981 over money and guidance. Motown was always out for itself as Motown was a business not a family.

LikeLike

That should read: “her ex-husband (Herman Griffin and she got divorced in early 1963, and Herman left Motown for Wilbur Golden’s Correc-Tone Records, soon after. He helped convince her to leave Motown, but it was really HER final decision in mid 1964, because she was miffed at Berry Gordy for charging his artists for studio time, and other services, and keeping a lot of money that she felt should have been hers. She really resented Herman’s trying to but into her life, and manage her business affairs, after their divorce. By mid 1964, she wouldn’t have followed his advice without really feeling the same way on her own. When “My Guy” became the number one National hit, and she was still not receiving much, she really decided on her own, to leave, and allowed her to decide to sue Motown, and to negotiate with 20th Century Fox. She found out later, much to her chagrin, that other labels (especially the Majors) treated her even worse.

LikeLike