Tags

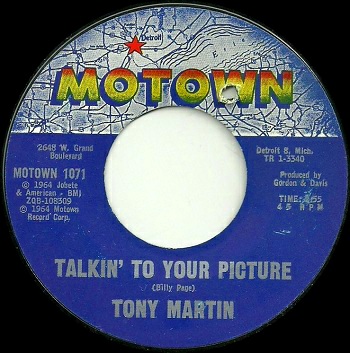

Motown M 1071 (A), November 1964

Motown M 1071 (A), November 1964

b/w Our Rhapsody

(Written by Billy Page)

Stateside SS 394 (A), March 1965

Stateside SS 394 (A), March 1965

b/w Our Rhapsody

(Released in the UK under license through Stateside Records)

Amos Milburn. Bobby Breen. Bunny Paul. Sammy Turner. And now, Alvin Morris Sr., better known as legendary crooner Tony Martin. Yep, Motown boss Berry Gordy sure loved to give recording contracts to washed-up singers alright. Especially singers with strong MOR credentials.

Amos Milburn. Bobby Breen. Bunny Paul. Sammy Turner. And now, Alvin Morris Sr., better known as legendary crooner Tony Martin. Yep, Motown boss Berry Gordy sure loved to give recording contracts to washed-up singers alright. Especially singers with strong MOR credentials.

No credible explanation has ever really been put forward for this rather noticeable trend. My own pet theory is that these bizarre signings (and there are more of them still to come) allowed Gordy – by now one of America’s most successful black business owners, never mind one of its leading music industry moguls – to live out a fantasy.

Partly, that’s to do with there being no real model for him to follow; in the past, the men who’d gotten really rich from the music industry had been loud, gregarious, cutthroat white guys, with expensive suits, big cigars, burly goons and a portfolio full of crooners, and so that’s what Berry aimed for too. But there’s another element to it.

A wealthy, accomplished black man in a palpably racist trade (and indeed a palpably racist society), not to mention the personal awkwardness that came from being a great songwriter and negotiator but also a high school dropout ex-boxer who found reading a chore… it’s possible, even tempting, to read the entire Motown story as Berry Gordy’s own personal quest for acceptance from his newly-acquired peers, many of them born rich, most of them older, most of them white. After all, in 1964, there were still places where, thanks to the colour of his skin, he’d have been turned away from clubs and ballrooms which he could afford to buy and raze to the ground if he so chose. I can’t even begin to imagine.

In that context, it’s moot whether or not Gordy ever believed any of these records could make him a dime (although Motown was never shy or self-conscious about chasing that dime before it rolled into the gutter); rather, I see this as part of a drive for “respectability”, a gesture of both defiance and pleading aimed at the kind of old-line snobbery that had kept the Gordy family, and black America, down for all these years.

Put simply, a million dollars opened a lot of doors; being able to boast you had signed Tony Martin, that might open a couple more, score you a couple more introductions, a couple more invitations. If the record sold nothing, who cares? It shows you’ve got money to throw away (almost literally) while playing the game. Act like it’s nothing, like you’ve never been hungry, like you’ve never had to watch the bailiffs lock up your little jazz record store, taking all your savings down with it.

Put simply, a million dollars opened a lot of doors; being able to boast you had signed Tony Martin, that might open a couple more, score you a couple more introductions, a couple more invitations. If the record sold nothing, who cares? It shows you’ve got money to throw away (almost literally) while playing the game. Act like it’s nothing, like you’ve never been hungry, like you’ve never had to watch the bailiffs lock up your little jazz record store, taking all your savings down with it.

And if one of these records from an “establishment” reject struck it big, well, what better way to cock a snook at that establishment? If it was 2004, you’d drive by with your gold chains and your gaggle of girls and your fur coat and your great big shiny car, playing your stereo loud, flipping them off, living it up at their expense; in 1964, you’d settle for a wry smile, the tacit acknowledgement that you’d got it right after they’d got it wrong. Very hip hop, that.

Which is ironic, because most of these Motown “over-the-hill crooner” records are so very un-cool, almost defiantly so. There’s a certain quality to their naffness in some cases; Bobby Breen bounding around like an over-excited puppy, Bobby Darin full of earnest conviction, Pat Boone pretending he’s twenty years younger. Other times, the results are just an excruciating soup of turgid, overblown slop. Have a guess which pile this one falls into.

A million-selling star of stage and screen in the 40s and 50s, Tony Martin was perhaps fifteen years past his prime – and almost nine years removed from his last big hit single – when Motown brought him back into the studio. Like Bobby Breen before him, he stuck out like a sore thumb in the Motown catalogue. Albeit an impeccably-dressed Caucasian thumb.

Out in California, the 50-year-old Martin worked with Motown’s LA office and its star producers Hal Davis and Marc Gordon, along with soon-to-be legendary soul writer Billy Page. The liner notes to The Complete Motown Singles: Volume 4 note the team’s attempts to update Martin’s sound with a pop-country vibe to match Dean Martin’s contemporary Sixties efforts, which had found commercial and critical favour. But the results might as well have been cut in New York in the early Fifties, because what’s on the record just doesn’t match up to that story at all.

Instead, this is the sound of an ageing vocalist slogging through a third-rate pseudo-show tune, delivering a strained, struggling lead vocal that manages to be syrupy and bombastic rather than vulnerable or toughened – don’t think Nineties Johnny Cash, think the last days of Elvis, only without the tragic subtext, and played on 33 by mistake.

If Martin sounds tired (in every sense), he’s not helped by the material. The song is a dud, and a creepy dud at that; it bears some lyrical similarities to Marvin and Tammi’s Ain’t Nothing Like The Real Thing, but this version makes the narrator sound like a potential serial killer rather than a lovestruck romantic.

You won’t accept my phone calls

My notes to you come back unread

I want to make you mine again

But you make me spend my time a different way instead…

Plus, it doesn’t even scan. The bit at the end of the first couplet in the chorus (“…begging you to come! back! / And be-my-wife”) is staggeringly amateurish; if this was a show tune, it’d be written out after the opening night.

The tune isn’t much better, either – there are a few pretty chord changes to momentarily break the torpor, but on the whole it’s decidedly lightweight piffle dressed up as deeply-felt gravitas, similar to the aforementioned Sammy Turner’s Right Now in that it’s all blaring bombast and choral overdubs and emotional cues without earning any of them, going straight for a big finish but not bothering with any of that tedious build-up nonsense.

As well as being a resounding flop artistically, this was also a resounding flop commercially, meaning Tony Martin’s Motown career should by rights have been quietly given up as a bad job. Instead, all parties carried on regardless, ploughing grimly ahead with more singles on both sides of the Atlantic. Berry Gordy wasn’t about to give up his status symbol.

Whatever the motivation, it’s a dud from start to finish. One of my least favourite Motown A-sides so far (which, given that we’ve had more than 250 of them, is quite the accomplishment), this is an embarrassing mis-step for both singer and label. Unfortunately, there’s rather more where this came from.

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in Tony Martin? Click for more.)

|

|

| Ray Oddis “Happy Ghoul Tide” |

Tony Martin “Our Rhapsody” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

Maybe not too many of these were pressed because I don’t recall it even in remainder to bins to be bought accidentally on the power of the label alone.

Nixon, I guess you were only about 15 in 1993, when To Be Loved was published, otherwise I’d wished you had written it instead of Gordy himself. Your psychological hypothesizing in the first half of this review is exactly what that book sorely needed, and is indeed a piece of a book that still needs writing. I can’t remember right now if Gordy even fleetingly mentions Martin in it.

Somewhere in Nelson George’s Where Did Our Love Go, Martha Reeves is quoted as saying, “I think I was first person in the sixties to ask where the money was going.” Well, Martha, here’s some of your answer and ours. By this late in 1964, even pre-teen white kids understood that the Motown, Tamla and Gordy labels were about good music by young black people. If this other stuff had gotten any higher profile, it could have become very confusing.

Nothing against Martin personally, and here’s hoping he and Berry parted on as amiable terms as they began.

LikeLike

I agree with you Dave! I actually read To Be Loved a few yrs. back and feel the samw way you do about it. Though BG has never struck me as a tell the truth nothing but the whole truth guy. Half truths + positioning himself in a the best light possible seems to be more of his swag. Lol. Yet I still have the utmost respect for the guy.

LikeLike

When people think of odd Motown signings they often point to the signing of Irene “Granny” Ryan of the Beverly Hillibillies. This actually made some sense … The “Pippin” Musical Sndtrack was on the Motown label in the early 70s. Miss Ryan was the star of Pippin so I guess it might make some odd sense for Motown to sign her as an artist. Don’t quote me on this but I think the few singles she had on Motown were Pippin related. Sadly, Miss Ryan died during Pippin’s run. Speaking of Pippin, several Motown artists recorded songs from it. (Jackson 5 did “Corner of the Sky” while the Supremes did “Guess I’ll Miss the Man”)

LikeLike

Wow! Never would’ve thought Granny from Beverly Hillbillies was on Motown. Well I’ll be- doesn’t that sound like something Jethro or Ellie Mae would say? Lol.

Miss Ross also cut a version of “Corner in the Sky” too.

LikeLike

This record is a harmless sing-along. It’s not cringeworthy like Ray Oddis and deserves 3/10.

Tony Martin’s signing to Motown had one unforeseeable result. A decade later his son Tony Martin Jr was half of the duo Martin & Finley. Tony Martin used his connections to secure the duo a recording contract, and the album “Dazzle ‘Em With Footwork” was released on Motown in 1974.

LikeLike

Great piece of trivia! I had no idea.

LikeLike

R.I.P. Tony Martin, Died 27 July 2012, Aged 98.

LikeLike

I’m glad you mentioned his recent passing, 144man. While I could never really understand Martin’s appeal (at age 60, I predate his fan base of the 40s and early 50s), I see his signing with Motown as a sincere effort on the part of both parties to score a genuine hit. He was married to legendary MGM dancer Cyd Charisse for many years (her death preceded his a few years ago), and even a year before his death he was singing in cabarets. You gotta hand it to the guy for that! Last night I subjected myself to a viewing of one of his (few) films, “Hit the Deck,” an MGM sailors-on-leave musical from 1955 that was godawful. But it wasn’t Martin’s fault.

LikeLike

That really saddens me! another great talent has passed away! in his hey day he was a force to be recon with in his field of music, wow ,what a career!!! I was a little late to be able to enjoy some of his films but the long life of talent in both venues is a real testimony to longevity!! He had lived A long and prosperous life!!!! 98 years that is 2 years shy of 100 !!!!! So many Greats in their Field are beginning to Pass away but no one to take up the torch and carry On!!!! and Tony was just so recently!! back just in July?? I give All my best to all of his family and R.I.P.Tony, you will be missed and never be forgotten!!!!

LikeLike

I think this was an attempt to broaden Motown’s acceptance into the easy listening or M.O.R. (middle of the road) markets ,By this time Berry wanted his company to be accepted and played on the radio and known as a all around record company that could cross over in to different formats . not just a soul or ” black” Known for company but rather a record company that had some great artist that any one could listen to and their songs could be enjoyed by anyone no matter what the coluor. But certainly this was not a commercial success!! at this particular time .. but it was the beginning!! especially latter. as Motown acts where being accepted into some of the well established clubs like the Copa etc. just a year latter in 1965! and others that where exposing the talents of Motown acts to some more of the white audience etc. I think with the out of the bag thinking that a long established artist that had hits in the past which sounds like something out of the 40’s or1950’s doesn’t make the grade here!!! But in Detroit some of these formats Motown just did not have the experience marketing in these different formats like for example the country MELODY issues the material didn’t match the times or maybe the artist! Thankfully Gordon& Davis later grew and went on to produce some of great songs . And of coarse this was the first California or west coast as called in Detroit Experiments!! The success at the time was Brena Holloway!!!, but of coarse The material Matched the artist and the time in 1964!! Nothing against tony but this one is a dud as far as material goes and he sounds like he was singing it in a outdated style!!! but there again at the time this was done out side of Detroit with west coast producers at the time and writers and wasn’t marketed properly for that kind of format of music . I think that the rating of 1 is a little harsh for the effort for Tony, but even if I were to give it a “2” I’m afraid that I still be thinking as a “1” in my mind. SORRY!!!!! So at least for this one I would have to agree with the rating of “1”

LikeLike

I agree with the rating of 1. It’s a sub-par song, done poorly, with a has-been singer singing a 20-year too old style and doing it on autopilot. It had absolutely no chance of even making one sale. When it was out I saw plenty of full-coloured stock copies lying around in bargain bins and thrift stores. The interesting thing is that I saw almost NO DJ copies! In any case, Motown did NOT know how to market this kind of music. The same thing happened (but to a less grievous extent, with Billy Eckstine. At least his relatively modern cuts sold some, and ample copies where seen all over (to wit: “Thank You Love”-a classic mid ’60s Motown/Soul sound written for Stevie Wonder.). Even “For Love of Ivy” had some sales, and was fairly commonly seen around, probably due to the fact that the arrangement and instrumentation had a fairly contemporary sound, unlike the Tony Martin drek. I agree that Berry Gordy used the signing of Tony Martin to help show that his company had a wide range of music and artist types and genres, knowing that he’d probably get no sales from it.

LikeLike

I was a bit surprised that Gordy didn’t come up with a label for the MOR performers. After all, there already was Stein & Van Stock for their MOR songs. Instead, this was Jobete and Motown, neither of which could be helped by this, or needed it.

LikeLike

I think Gordy put all these MOR “names” on his flagship label — Motown — to give it some adult “cred.” Pretty laughable in hindsight.

LikeLike

Bingo. If there’d been a “Van Stock Records” or somesuch, it would have given the impression that Motown, Tamla et al were seen as second-rate labels, labels trading in stuff strictly for the kids (or, more pertinently, for young black audiences) – maybe Marvin and the Supremes might have demanded a transfer to the grown up label! Instead, the whole enterprise was status building; the Supremes and the Four Tops, labelmates – and more successful labelmates – of Bobby Breen and Tony Martin.

LikeLike

Good thoughts there Nix. Motown could have gone in several directions here & I think they mostly made the right moves. (Not sure I would have sent the 4 Tops to Broadway but that’s just me!) In the 60’s some of the snooty rock critics (who today fall all over Motown with praise) would harshly criticize Motown for their “outdated Ames Bros/Andrews Sisters routines” on TV show like Ed Sullivan. I mean I remember 4 lads from Liverpool who had some MOR in their blood! (Can we say “Till There was You” or “A Taste of Honey”?) I don’t remember much criticism there.

LikeLike

Yo Robb! Did Billy Eckstine record a version of “Thank you Love”? Was it ever on a single? I’ll have to check it out. Love Stevie’s version!

LikeLike

He did, and we’ll be meeting it soon enough!

LikeLike

He certainly did. And it was a minor hit on several Soul stations around the US. And he sang it like a “Soul singer”, rather than an MOR guy! I think it’s, by far, his best Motown recording. it’s also got the “A” instrumental treatment (better than Stevie Wonder’s). in my opinion.

LikeLike

Ouch! Another 1 smh. This just isn’t the sound I asociate with Motown – The Sound of Young America! This sounds more like The Sound of Boring Middle Age America. Lol

The first time I ever heard of Tony Martin (a few yrs. back) I was watching a Lana Turner (then starlet, she wasn’t the platinum blonde bombshell that she would soon become) film from the early 40s on TCM. He sang some jazzy up-tempo number and sounded pretty decent. Here, its another story. Steve D. gave an accurate description when he said Martin sound tired. Who wants to hear some tired old man when you have rock n roll? Lol

I can understand BG signing Martin, but this was just a waste of time. Steve D. I completely accept this 1/10 verdict & I agree with your theory on BG.

LikeLike

Poor Tony. I vaguely recall him being some magazine ads in the late 60s for some fitness equipment or something. You know something like “And this is how singer Tony Martin keeps in shape!” LOL! RIP Mr. Martin. He must have done pretty well to live to the age of 98!

LikeLike

Hi Again – Damecia I had to comment on your comment about the Sound of Boring Middle Aged America… One thing that always irked me about Motown was the way they tried to turn their own artists into MOR singers. In the late 60s/early 70s I saw several Motown groups in concert (Diana Ross/Supremes; Temptations; Smokey & Miracles) In their concerts the hits were generally relegated to medleys while more time was spent on standards/show tunes/hits of the day, etc. The artists performed these songs reasonably well but I wanted to hear the hits!!!! The same thing happened with the TCB TV special with the Temptations/Supremes. From a business perspective I can probably understand this – I’m sure tons of cash was brought in from the supper club/Vegas styled venues but really I guess Motown wasn’t too worried about the opinion of a pre-teen white boy like myself!

LikeLike

Hey Robb, Did you (or any of our other friends)ever see any of these artists in concert during the time periods I mentioned? Would be curious to hear others’ thoughts on this subject. All the best to everyone out there in Motownland!

LikeLike

Lol I feel kinda wrong for laughing, but I can just picture the cheesy old skool ad which you mentioned.

LikeLike

Thumbs up on “The Sound of Boring Middle Age America”, which I’ve only just seen.

LikeLike

Some potential Tony Martin Motown album titles :

“Tony Martin a Go Go”

“Tony Martin – Puzzle People”

“Tony Martin – Soul On the Rocks!”

“Tony Martin – Dance Party!”

Okay I’ll stop!

LikeLike

“Tony Martin Dance Party” sounds like possibly the least appealing album in the history of the world, right after “Tony Martin’s Down Home Polka Jamboree”.

LikeLike

I distinctly remember seeing Tony Martin doing a good idea guest appearance on The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson (a very popular late night talk show, for those who do not reside in the USA) ostensibly to promote this record in late 1964. When Johnny introduced the song and mentioned that it was on the Motown label, I almost fell out of my chair. Tony Martin? Motown? Is there something wrong with this picture? But on second thought, I was kind of proud for the company that had awakened the world to so much young black talent that it could include a celebrity with a significant history of mainstream recording success.

Then I watched him sing the song. It was the last time I heard it until I opened Volume 4 of TCMS, but over those 51 years I had recalled 2 lines from the chorus: “Talkin’ to your picture” naturally and “Darling if you don’t” which was one syllable shorter than the line, forcing Tony to stretch the word “don’t” into 2 beats, which always seemed incongruous to me; as incongruous as Tony Martin recording for Motown.

But don’t get me wrong. Tony was a big deal in the entertainment business in his time. He had his own TV program and made some movies. As an actor, he was a good singer, but he had the looks to pull it off and have the starlets falling for him left and right. He had enough hit records to be considered a successful pop singer. The “Tenament Symphony” noted in TCMS Vol. 4 is the one with the lines: “The CCohens and the Kellys, the Campbells and Vermicellis.” That song always hit home for inhabitants of NYC, so accustomed to living in close contact with families of so many nationalities, most of whom were immigrants or the sons and daughters of those who had arrived from faraway lands. It was corny, but meaningful. That’s where Tony was at home, not Hitsville.

LikeLike

Sorry about line one. i am using a loaner phone with an out of control spell check. The words “good idea” mysteriously came from cyberland.

LikeLike