Tags

Soul S 35008 (A), January 1965

Soul S 35008 (A), January 1965

b/w Hot Cha

(Written by Autry DeWalt Jr.)

Tamla Motown TMG 509 (A), April 1965

Tamla Motown TMG 509 (A), April 1965

b/w Hot Cha

(Released in the UK under license through EMI/Tamla Motown)

Before sitting down to write these reviews, I knew 1965 was Motown’s biggest year to date in almost every sense – but I hadn’t realised quite what a strange start to the year was in store.

Before sitting down to write these reviews, I knew 1965 was Motown’s biggest year to date in almost every sense – but I hadn’t realised quite what a strange start to the year was in store.

So far, since the beginning of January, we’ve had a very pretty but somewhat out of character big ballad from the Four Tops (Ask The Lonely), followed by two unreleased singles by long-forgotten acts from the rougher, tougher early days of Motown. And now, look, here’s a big hit single to get us back on track – except it’s Junior Walker, who was never in step with whatever else was happening for his labelmates.

“Junior Walker” was saxophonist Autry DeWalt Mixon Junior, who had arrived at Motown as part of a job lot, acquired with a bunch of other refugees from the Harvey/Tri-Phi empire when Motown bought out the rival company. But that makes him sound like a reject, an afterthought; in fact, a delighted Berry Gordy welcomed Junior into the Hitsville fold with open arms, BG perhaps sensing an opportunity to “ground” his ever-expanding label before it drifted entirely away from its original R&B fanbase and his supporters in black radio. A few down-home R&B chart hits and the tide would be turned.

As he always did whenever anything was asked of him, Junior delivered the goods.

Not only did he provide an anchor for the new Soul Records imprint, a Motown subsidiary positioned to push the grittier sounds that wouldn’t sit next to Tony Martin in the racks or on the airwaves, but he also sold great big truck loads of records, boosting Berry Gordy’s bank balance as well as his ego.

More than any other act in 1965, Junior Walker and his All-Stars were absolutely crucial to Motown finding its true role in the music world, Walker giving Gordy an instant, ringing reposte to critics who claimed he’d lost touch with his roots (not to mention those activists who went a step further, saying Motown wasn’t doing enough for black culture in general). Much easier to deflect such criticism when you’ve got the hottest record in the country, which opens with a gunshot and two minutes of gutbucket sax. Eat that, Memphis.

More than any other act in 1965, Junior Walker and his All-Stars were absolutely crucial to Motown finding its true role in the music world, Walker giving Gordy an instant, ringing reposte to critics who claimed he’d lost touch with his roots (not to mention those activists who went a step further, saying Motown wasn’t doing enough for black culture in general). Much easier to deflect such criticism when you’ve got the hottest record in the country, which opens with a gunshot and two minutes of gutbucket sax. Eat that, Memphis.

NINE TWENTY SIX EAST McLEMORE

That’s right – Walker topped the R&B charts with Shotgun (and took an unexpected but very welcome pop Top Five slot to boot), in the process reclaiming vital market share on black radio from an emergent and unmistakeably worrying rival in Stax.

In many Motown histories, the Memphis label is painted as some kind of arch-nemesis, a sort of equal and opposite force which competed with Motown throughout the Sixties and early Seventies for the soul of American pop music, not to mention fans’ dollars. Sixties Stax was, and continues to be, marketed as the cooler, tougher, more soulful and altogether more hip alternative to fluffy, stuffy, pop-fixated old Motown, and those DJs (black and white) that considered themselves hip to new sounds took the best Stax cuts immediately to heart.

Although Stax were themselves ironically a white-owned label, they knew their hardcore fan base was urban African-American teens, and they very deliberately positioned themselves as the Motown alternative for discerning black audiences. You’re deliberately panel-beating your street artists into professional entertainers, going so far as to publicly declare they’ll play the White House or Buckingham Palace? We’ve got the real sound of Young America, and it’s gritty, it’s dirty, it’s raw and it’s black. You’ve got Hitsville? We’ve got Soulsville.

Seems fair on the face of it, right? After all, only one of these labels signed Pat Boone, or released an album of songs from Funny Girl. Stick your hand blindly into the, um, stacks and pull out a random record from each pile to play to your elderly aunt – without looking at what it is you’ve grabbed, are you more comfortable playing the Motown 45, or the Stax one? Plus, as I’m always being reminded, wasn’t Stax just so much more daring, providing listeners with a more interesting, varied bag of musical textures? (Even now, when I’m talking to new people and this blog comes up, one of the most common responses runs along these lines: “Every Motown single, eh? Doesn’t that get a bit samey? Hope you don’t mind me saying so, but I actually always preferred Stax myself.”)

(Or Okeh, but that’s a story for another day.)

Anyway. Wrong on all counts.

I don’t want to turn this into a straightforward “Why Motown > Stax” screed, especially since Stax came up with so many great, great records. Instead, well… it might come across as naive or hippy-dippy to ask why Motown and Stax fans can’t all just get along, and enjoy all the wonderful music, but it’s a fair question to me. The supposed differences between the two catalogues turn out to be nowhere near as exaggerated as has been made out, as any intermingling of the two labels’ Complete Singles box sets will quickly show; the two sets of legendary house musicians have a different sound to each other, there’s no getting away from those incredible Stax horns and the omnipresent thumping bass drum Motown never really copied, but otherwise, you could pretty much slot any Stax side into the running order of The Complete Motown Singles without unduly confusing listeners, if not necessarily vice versa.

(In fact, what that exercise does highlight, surprisingly, is that if anyone adhered to a rigid formula with their 45s, it was actually Stax; the big hit Stax sound and the big hit Motown sound are both readily identifiable, but Motown released something like five times as many records as their Tennessee rivals, and as readers of Motown Junkies will already know, that gave Motown significantly more room to indulge in all kinds of oddities – in these first seven years, we’ve had R&B records, pop records, jazz records, blues records, gospel records, doo-wop records, comedy records, spoken word records, white guitar pop records, records made from clips of other records, ballads, dancers, stompers, weepies, rockers, slowies, and whatever else you care to mention.)

But marketing is a powerful thing, and if much of the difference is in the mind – like different brands of corn flakes or something – then Stax played a stronger hand in making up people’s minds for them. Motown’s move to the mainstream raked in millions, but Stax’s canny marketing, playing up their supposed comparative “authenticity” (guts over hooks! soul over sales!) was a winner with black hipster audiences, and therefore black radio, and therefore white hipster audiences, and therefore Stax was “cooler” than Motown, and so it remains to this very day.

TWENTY SIX FORTY EIGHT WEST GRAND

The two biggest misconceptions I’ve come across when doing this blog: firstly, that Otis Redding recorded for Motown, not Stax. And secondly, not far behind, that Junior Walker and the All-Stars recorded for Stax, not Motown. Both wrong. But listen to Shotgun and think about that.

Regular readers will know of my love/hate relationship with the saxophone; thanks to countless tasteless MOR cheese merchants, the instrument has had responsibility a lot of musical atrocities laid at its doorstep, and an ill-judged sax part can ruin an otherwise fine record more than any wayward vocal or dropped beat. Junior Walker, surely one of the all-time greats, was as bad a judge as anyone, capable of veering from smouldering cool to mugging ham in the blink of an eye, a naturally talented guy with supreme skill who clearly had no idea what made his records good or bad (or, indeed, which ones were good or bad, or even that there were any bad ones at all).

Regular readers will know of my love/hate relationship with the saxophone; thanks to countless tasteless MOR cheese merchants, the instrument has had responsibility a lot of musical atrocities laid at its doorstep, and an ill-judged sax part can ruin an otherwise fine record more than any wayward vocal or dropped beat. Junior Walker, surely one of the all-time greats, was as bad a judge as anyone, capable of veering from smouldering cool to mugging ham in the blink of an eye, a naturally talented guy with supreme skill who clearly had no idea what made his records good or bad (or, indeed, which ones were good or bad, or even that there were any bad ones at all).

There are, but this isn’t one of them. This is excellent.

I once read a critique of Junior’s material that called him and the All-Stars the purest musicians ever to score hit records, and called those records little more than glorified jam sessions (and meant it as a compliment). Junior, who wrote this himself – the only solo writing credit he copped for any of his big hits, though he’d have a hand in penning most of them – did indeed often adopt a jam-based approach to songwriting, coming up with a groove and riffing on it rather than sitting down to write a tune. But that’s not to say the results couldn’t be every bit as arresting as a heavenly Holland-Dozier-Holland chorus or a beautiful Smokey Robinson melody; by playing to his strengths (and those of his cadre of buddies, the original All Stars, a crew of fire-breathing jazz rockers who terrified and delighted live audiences), the grizzled Southerner who couldn’t even read became one of Motown’s great craftsmen of hit records. Walker may have been illiterate, but damn, the man could write a song.

This was the first and biggest of Junior’s hits, but even taking sales and stardom out of the picture, it also marks the start of a new era for the All Stars, because this is where they discovered their secret weapon, a killer new ingredient to stir the pot: Walker wasn’t just a fine and instinctive writer, or a great horn player, but he could sing too.

The story goes that while Junior had come up with some lyrics for Shotgun, the original vocalist he’d invited to sing lead on the track didn’t show up, and so Berry Gordy (who liked Walker personally, and who was co-producing this session) demanded Junior himself step up and cut the song. He nailed it; Walker’s gruff, bluesy delivery added a whole extra dimension to the All Stars’ sound, an arresting dimension that makes this twice the record it would be without him. He’s an instant and obvious star, a charismatic and sexy lightning rod for radio listeners to zero in on, a “double threat” singer-musician in the Stevie Wonder class; it’s as if James Brown had suddenly picked up a sax.

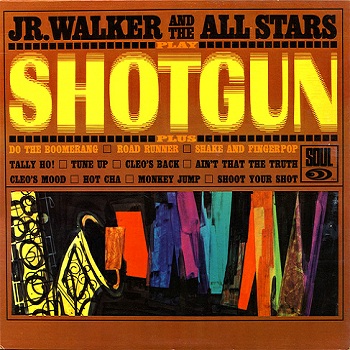

Shotgun is the All Stars’ monument even before Walker steps up to the mic – the cartoon sleeve (left) and opening “gunfire” sound effect give some idea of the playful rock-out that’s about to follow, but then a trembling, vibrating drum fill (believed to be the legendary Motown house drummer Benny Benjamin, rather than the All Stars’ regular skins man Tony Washington) and a thudding, finger-shredding James Jamerson bass part (the All Stars had no bassist of their own) heralds the entrance of Walker’s best sax performance to date, almost deafening in its squealing intensity. You can practically feel the hum of energy buzzing off the man.

Shotgun is the All Stars’ monument even before Walker steps up to the mic – the cartoon sleeve (left) and opening “gunfire” sound effect give some idea of the playful rock-out that’s about to follow, but then a trembling, vibrating drum fill (believed to be the legendary Motown house drummer Benny Benjamin, rather than the All Stars’ regular skins man Tony Washington) and a thudding, finger-shredding James Jamerson bass part (the All Stars had no bassist of their own) heralds the entrance of Walker’s best sax performance to date, almost deafening in its squealing intensity. You can practically feel the hum of energy buzzing off the man.

When Walker himself passed in 1995, he had “JUNIOR (SHOT GUN) WALKER” engraved on his headstone, and with good reason – not only because this sold so many copies, but because it’s the best thing he ever recorded. His sax is peerless, his vocal is superb. He’s never on the track at the same time as his horn, so it’s entirely possible he recorded his vocal and sax in the same take – it certainly feels that way. In combination with keys man Vic Thomas’ blaring organ riffs, Walker turns Shotgun from a band romp into a full-on party. “We gonna dig potatas! We gonna pick tomatas!”, he bellows, and it’s impossible not to smile. Nelson George described this record as having “the kick of a bull and the greasy feel of a pigs’ feet dinner”, a description that’s stuck with me since I first read it – but while that captures it pretty well, it maybe downplays what a fun pop record this is too.

Because it is just a whole lot of fun. It’s also quite stupid, and proud of it (as with Stevie Wonder’s Fingertips, another unashamedly direct Motown stomper), but that plays in its favour; it’s a gas. As with pretty much every Motown record we’ve encountered so far in this strange new year of 1965, I like this better each time I listen to it, and so once again I’d better stop before the marks climb out of control. But good show, Junior Walker. Good show.

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in Jr. Walker & the All Stars? Click for more.)

|

|

| Hattie Littles “You Got Me Worried” |

Jr. Walker & the All Stars “Hot Cha” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

Walker fostered instant brand loyalty with this. I never fell off buying his records till maybe 1972 or 3. I don’t think most of us really saw a Soul label until this record, but with Motown on it also, we were informed he was ‘family’ too, even if his records didn’t have the full Funk Brothers familiarity of his labelmates.

According to the booklet with his “Nothing But Soul” set of the mid-90s, Walker “didn’t exactly live for the studio,” and thus there isn’t a lot of unreleased material waiting for sunlight. One that did come out, on the same various artists’ LP in 1986 as The Marvelettes’ “Knock On My Door,” was “Break It Up,” recorded in 1966. It’s a throw-down piece funk, no small compliment to his signature hit, with bass so rich it sounds like it could make a two hundred-pound console stereo dance all by itself.

I was jumping and down when my sister-in-law brought down her pay-per-view copy of “Misery” from 1990, and there’s Walker’s “Shotgun” over the opening credits, beautifully setting the tone for the crazed Stephen King thriller about to unfold. The song can also be heard in the last half hour of Spike Lee’s “Malcolm X,” fittingly as well.

It’s too easy to say this is my favorite Walker before the dividing line that is “What Does It Take To Win Your Love,” but I’ll be surprised to find if any of his 60s sides draw a true Rotten Tomatoes rating. As for my ‘favorite,’ “Tune Up,” “Road Runner” and the slinky “Cleo’s Mood” can never go neglected, but in fact, I bought them all.

Hello 1965!

LikeLike

A few points to add. Junior Walker and Shorty Long represented what was called

“Blue Collar or Factory Worker Soul” in Detroit. Stax president Al Bell and Berry

Gordy were friends and talked regularly as did Smokey Robinson and Curtis

Mayfield. Otis Redding was a Motown fan, he recorded “My Girl” and included it

in his live shows. Redding used the opening guitar riff from the Temps “I’m Losing You” in “Tramp” ,his duet with Carla Thomas.

Finally, if you ever get to Detroit, checkout Woodlawn Cemetary. It’s the final

resting place of David Ruffin, Lawrence Payton of the FourTops. The families of Berry Gordy and Diana Ross have cryps located there.

LikeLike

Oh wow never new that about “Tramp” but I definitely here it now.

LikeLike

Thanks for bringing in the influence of Stax. I have an old and great friend who championed the Memphis sound of that label as much as I did Motown. It was a friendly rivalry and of course we both admired some records from the rival label. But in the years since I first heard these records I’ve learned to really appreciate the music from Memphis, as well as to understand better my love for and increase my knowledge of Motown.

It really clarifies the discussion here to note the perceptions of what was seen as “genuine” at the time and to move on from that to an inclusive look at two indisputable sources of musical genius.

LikeLike

The funny thing was, Stax near the end of its run likewise began to “fall off the rails” in terms of whom they signed – the late British pre-teen singer Lena Zavaroni (“Ma! He’s Making Eyes at Me”), Glenn Yarbrough and a later incarnation of his old folk group The Limeliters, even popular daytime talk-show host Mike Douglas. (As would be specified below in prior posts.)

As well, given what would happen in later years to the song’s other producer, Lawrence Horn, that he co-produced this proved nothing short of ironic.

Still, I have to concur about this tune. Especially the mono mix.

I have to wonder what role the “Dynagroove” cutting process employed for many years starting in 1962-63 by RCA Victor at all its studios, including Chicago where virtually all sides on Motown and its subsidiaries were mastered up to 1972, played in the label’s success, in addition to all the elements that came together at Motown itself.

LikeLike

Yes, post-Atlantic Stax becomes an increasingly mixed bag; I should probably have clarified I was talking about both labels’ respective heydays. Very good point though.

LikeLike

“I said Shotgun!” I’ve been waiting for this review = ). My 14 yr old sister recently told me that all these yrs she thought I was weird because I listen to “old” music, but she recently discovered I wasn’t because another 20 something had “Shotgun” on their playlist on Tumblr. Lol. I laughed and then told her and asked her how many 14 yr olds would’ve even known the song and most importanly that it was Jr. Walker.

Steve D. I think this is my favorite review that you have written (that I’ve read) thus far. Really superb and proves why you won those awards! I especially love your take on the Motown vs Stax debate. I only wish you gave this song 1 more point! Lol. Why a 9/10???

Everything about this song screams fun. From the shotgun in the beginning to the DBever present bass, to Jr’s roaring sax, to his weird yet not bad distinctive vocals, to those crazy lyrics! Can someone tell me what this song means?!? Lol. I lb

LikeLike

Damecia, you said it perfectly yourself: “Everything about this song screams fun.” That’s what this songs means.

LikeLike

Shotgun: definitely a great hit. I’m looking forward to more Jr. Walker coming up; some of his underrated stuff really should have been played more often… but that’s for later posts.

I can’t remember if this was touched on before, but regarding the Motown purchase of Harvey/Tri-Phi; where could one look to read more about this phase in Motown’s history? Lots of the major books I’ve read on the history of Motown mostly ignore the Motown purchase of Harvey, Tri-Phi, Ric-Tic, and Golden World, except in the context of how Jr. Walker and Edwin Starr came to be signed with them. Yet I find this aspect incredibly interesting… are there either some good Motown histories or biographies written that explain this a little more?

LikeLike

Ben:

Regarding Motown’s acquisition of smaller labels, a Google search is a good

place to start. Check out the blog newmediacreative. com (November 2009), you’ll find info about Golden World Studios before and after it was purchased by Motown. I also recommend “Motown: Music, Money, Sex, and Power”

by Gerald Posner. Enjoy.

LikeLike

Saxophone is my favourite instrument, and Junior Walker is one of my favourite sax players. I like many of his songs better than this one. I’d give it a 7. I bought it immediaiely, when it was first out, and got the special record jacket (scan above). I’ll never understand why there weren’t many more Jazz/Soul instrumental artists of his ilk on Motown’s family of labels.

LikeLike

One thing overlooked in this discussion is that this 45 came with several label errors–some copies have the artists listed as “Jr Walker and ALL THE STARS”–others have distributed by Bell records at the bottom–and some of these have tht statement blacked out.

LikeLike

Junior had particular bad luck with label mistakes (we’ll meet his famous hit “Leo’s Back” in a while), but it’s a basic rule of the universe that industrial printers will get things completely wrong and Motown weren’t immune.

Lars LG Nilsson, who provided so many of the great label scans for this site, has compiled a series of the best Motown label mistakes which makes for entertaining reading (I particularly like “Two Many Fish In The Sea”):

http://www.seabear.se/mistake1.html

LikeLike

It’s a dead link.!!!

LikeLike

No it isn’t. Though Lars’ whole site does occasionally seem to go offline from time to time.

LikeLike

Love your review! I always listened to it as a quasi-instrumental. Great party record! Rating: 10/10

LikeLike

An old, dear friend commissioned me to compose a piece as a memorial to his beloved late sister. Knowing my love for Motown, he wanted me to work that in at some point. I had never thought I could have access to that language in my own creative work, or find some interface between soul, symphony and opera that I could feel at home in. But I resolved to try, bought the book of Jamerson transcriptions, studied such long-loved songs as ‘Heat Wave’ and ‘Shotgun’ – and found my way in. The piece, to be called ‘A deep clear breath of life’ is a fantasia for alto (not tenor) sax and piano, and it includes a section called ‘Homage to Junior Walker’ – it doesn’t pretend to sound like Jr Walker, but I feel that I was able to tap into some of that glorious wildness and say something of my own with it. I wrote it for the wonderful saxophonist Dr Jennifer Bill, and she will perform it at her faculty recital at Boston University next February. I was so happy to learn that there was a space for soul to have its influence on my creative work. I wish Jr Walker were still around so I could thank him personally. In case he’s listening: thank you Jr Walker, and thank you Motown. And thank you, Peter, for giving me this adventure.

LikeLike

I bought the Shotgun album a couple of months ago & have been playing it to death ever since! The score you gave Monkey Jump is a travesty, every track is at least a 7 (maybe not Hot Cha), & there are at least six 9/10 pointers- looking forward to your review of Shake & Fingerpop! This track/album shows that the band reached Motown fully formed & firing on all cylinders straight away, no period of development necessary here.

Also, listening to the album shows what a great band they were. I saw them at De Montfort Hall, Leicester in about 1971 with my great pal Paul, sadly deceased, who said at the time that Jnr Walker was such a great saxaphone player that he could also play the boxes they came in!

LikeLike

Excellent review as always! I completely agree with giving this great tune a “9.” I’ll have to disagree, however, about this being Junior’s best recording. IMO, that honor goes to a song on his first album that wasn’t released as a single until 1966!

LikeLike

I can remember the first time hearing “Shotgun” on the radio…I was a kid listening to CBS-FM here in New Jersey when I heard that gunshot sound over the radio, and I was hooked!

Only later when I started collecting CDs did I find other gems – “Gotta Hold On To This Feeling,” “Tune Up,” “Shake & Fingerpop,” and of course “What Does It Take (To Win Your Love).” All great songs that have you hooked from the first beat.

Thank you very much for this website – as someone who missed growing up with this music (I was born in the late 80’s), this is a great way to learn a bit more about the music I love and listen to on a daily basis.

Thanks again!

LikeLike

This was the record we would always play to people who said that all Motown records sounded the same. I never did find out what the dance steps for The Shotgun were.

LikeLike

A word of props too about the Shotgun album.

Where Did Our Love Go & More Hits; Playboy and the Marvelettes ‘pink album,’ Sing Smokey, Temptin’ & With A Lot O Soul, Four Tops, Second Album & Reach Out, Uptight, Going To A Go-Go & Moods of Marvin Gaye … Shotgun deserves to be regarded in the company of all of those terrific albums of his lablemates, supplying Walker with memorable singles for an entire year to come, and even revisited for a 45 in the summer of 1967.

Like those other LPs, it’s enjoyed all the way through without skipping a single track. Released May 31, 1965, it would soon prove at least half a “Greatest Hits” in its own right.

LikeLike

Hi Dave L… I looked up some info on the number 1 albums on Billboard’s R&B charts from 1965. Various Motown albums (including some you mention) held a solid consecutive 22 week block at #1. Pretty cool, eh?

LikeLike

This is a great song though for some reason I like “Shoot Your Shot” a bit better. Regarding Stax & Motown. Both companies produced some great soul records. Period. I like both equally well. By the way, Stax wasn’t above “sweetening” some of their records with string arrangements – listen to “Private Number” by William Bell/Judy Clay or “Never Found a Girl” by Eddie Floyd. And, of course, Motown could do gutbucket soul when they wanted to. When I started buying 45’s I bought both Stax & Motown singles (& of course, many on Atlantic as well!) Oh and if anyone claims that Stax never released records by the likes of Tony Martin, I have 2 words for you … LENA ZAVARONI! LOL!

LikeLike

Another few words on the whole Stax vs Motown debate … It is interesting to note the artists that recorded something for both labels including Mable John, Kim Weston, the Emotions (on Motown in the 80s) and … drumroll please… Billy Eckstine! Can anyone think of any other artists who recorded for both labels? Even though they didn’t actually record for Stax, didn’t the Temptations do some recordings with Stax musicians in the mid-70s for their “House Party” album? By the way, take a listen to the Emotions recording of “Put A Little Love Away” for Stax. That is the most pop-sounding song they have ever released! No matter what people say, Stax was just as interested as Motown in having crossover success. Records like “Soul Man” & “Tramp” obviously clicked with the record buying public. Okay, okay I’ll get down from my soapbox!

LikeLike

Wow! I just found out that Mike “Men In My Little Girl’s Life” Douglas (talk show host) recorded a single for Stax records. Hmmm! No disrespect intended to either Stax or the memory of Mr. Douglas (who did host many soul artists on his show) – just thought it was interesting.

LikeLike

Stax had visions of grandeur and, indeed, ambitions to become a diversified record company, with sales in various musical fields (thus their wasting money recording artists in markets which were outside their staff’s experience. They went broke in the 1970s, and I can’t help wondering if those ambitions might, at least, have played a small part in their demise.

LikeLike

Stay on the soap box! I’m learning alot about Stax with you guy conversation about them. Interesting to find about Mike D.

LikeLike

Steve Cropper produced two tracks on “House Party,” both recorded in ’74, by which time Stax was pretty much a spent force.

LikeLike

Instant party baby! Just add water (or booze).

LikeLike

Don’t forget to bring sandwiches!

LikeLike

We already got ’em. Plenty or chopped bbq, pork chopp and fried chicken sandwiches!!

LikeLike

The Ultimate dance tune; this should be considered a “10″!

LikeLike

“A report from a rifle starts this and it is out of sight! A fantastic record from every point of view. Jr Walker sings out backed by chicken sax and violent organ. Too, too much! An absolute must when it is issued here. 5/5

“Flip is more subdued. An instrumental that lacks the breath taking quality of the A side, but good none the less. 3/5”

[Dave Godin, Hitsville U.S.A. 2, 1965]

LikeLike

one of my fave things about this incomparable (10/10) track is that before its fade, depending where my ears are at, I can hear any of ‘twine time’, ‘prime time’, ‘crying time’ or ‘frying time’…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha, you’re right! It’s like the videos of the train or the spinning mask where you can change direction by just using your mind (see also Yanni/Laurel!)

LikeLike