Tags

UNRELEASED: scheduled for

UNRELEASED: scheduled for

Soul S 35009 (A), January 1965

b/w Too Many Fish In The Sea

(Written by Henry (Hank) Cosby, Mickey Stevenson and Ivy Jo Hunter)

Tamla Motown TMG 506 (A), March 1965

Tamla Motown TMG 506 (A), March 1965

b/w Too Many Fish In The Sea

(Released in the UK under license through EMI / Tamla Motown)

Well, here’s a momentous first for Motown Junkies: a single that came out in Britain, but not in America. (And moreover, we in Britain got it twice. Of which more later.)

Well, here’s a momentous first for Motown Junkies: a single that came out in Britain, but not in America. (And moreover, we in Britain got it twice. Of which more later.)

The Tamla Motown imprint, whose iconic (for British readers anyway!) black and silver labels (pictured above for the first time) defined “Motown” for a generation of UK listeners, was inaugurated with a whole sweep of new single releases on 19th March 1965. The result of a marketing partnership between Motown in the US and EMI in Europe, Tamla Motown – a label which never existed in America – replaced Motown’s previous licensing arrangement with Stateside Records, and was designed to give Motown proper representation in the world’s most music-mad market. Possibly because there was little else to do, British teens in the 1960s and 1970s spent more money per head on records than anyone else on Earth, and now Motown had a platform to launch a real bid for their share of those pounds, shillings and pence.

Motown had had UK hits before – the Supremes’ Baby Love had even hit Number One – but now they had a brand, an identity, an iconic new beginning, borne of a new label where Motown’s big American hits wouldn’t be rubbing shoulders with the likes of Santo and Johnny, Herb Alpert or Brother Jack McDuff.

Tamla Motown launched with a bang, the new label selecting no less than six singles to come out on the same day, and a seventh a week later: seven 45s they felt best captured a true picture of what Motown was all about for UK newbies. British fans will be able to reel these off without looking, but EMI’s choices are illuminating: they picked new sides from the Supremes, Martha and the Vandellas, the Miracles, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, the Four Tops… and Earl Van Dyke.

Keyboardist Earl Van Dyke, leader of the immortal Motown house band the Funk Brothers (promoted here to a full label credit, but hastily rechristened “the Soul Brothers” as Motown boss Berry Gordy disliked the word “funk”), perhaps the most vital cog in the Motown hit-making machine, thus managed to appear on all seven of the first “real” British Motown singles. Van Dyke had already had a run-in with the Hitsville top brass over his future, and it’s usually painted as a straightforward tale of Motown actively thwarting his ambitions: the pianist eagerly awaiting his long-promised chance to cut some real jazz records under his own name, Motown keen to keep their valuable studio player under lock and key and prevent him from becoming a star.

The truth, as always, is a little more nuanced than that.

Earl Van Dyke was eventually given permission to record some cuts during the Sixties, but it was rare for him to be doing the kind of material he wanted. (Rare, though not unheard-of, and we’ll be meeting perhaps the “pure” Van Dyke/Funk Brothers sound before the year is out). Earl and the Funks’ first Motown single proper for three years, the energetic dancer Soul Stomp, had been moderately well-received (if not exactly well promoted), but it wasn’t what either the band or the label wanted. An impasse loomed on the horizon.

As a way of pacifying the usually good-natured Chunk of Funk, Motown A&R chief Mickey Stevenson – positioning himself, as he often did, as a supposed intermediary between the studio musicians and the President’s office – suggested Van Dyke record some “halfway-house” type records to begin with. The proposal was for an LP of Motown hits and other completed band tracks, but with the lead vocals scrubbed off and Earl’s rippling organ overdubbed in their place.

As a way of pacifying the usually good-natured Chunk of Funk, Motown A&R chief Mickey Stevenson – positioning himself, as he often did, as a supposed intermediary between the studio musicians and the President’s office – suggested Van Dyke record some “halfway-house” type records to begin with. The proposal was for an LP of Motown hits and other completed band tracks, but with the lead vocals scrubbed off and Earl’s rippling organ overdubbed in their place.

Stevenson had played a winning hand. Motown agreed to Mickey’s plan in the hope it would keep Earl happy for a while, and maybe sell some records while sticking to the script; Earl agreed in the hope it would lead to future releases where he’d have more freedom. But neither party was truly happy with the deal.

Earl, who was no idiot, knew he was being patronised and that Motown had no great ambition to promote him as a “serious” artist rather than a performing monkey.

Berry Gordy, shrewder still, was indeed wary of doing any more than the bare minimum to push Earl’s career. But here’s my theory. Gordy wasn’t only reticent because Van Dyke and the rest of the studio band were so important to Motown’s future success, but also for another, stronger reason, one which got right to the heart of the matter: these “Soul Brothers” organ overdub records aren’t all that good.

The slated first single from those sessions, All For You – an adaptation of a track originally known as Make No Mistake and recorded (with vocals) by both Marvin Gaye and Jimmy Ruffin as Lucky Lucky Me – was pulled from the American schedules before any promos were pressed up. Various reasons have been given for this. Motown didn’t want Earl to be a success, we’re told. Motown deliberately sandbagged Earl’s career, we’re reminded.

The slated first single from those sessions, All For You – an adaptation of a track originally known as Make No Mistake and recorded (with vocals) by both Marvin Gaye and Jimmy Ruffin as Lucky Lucky Me – was pulled from the American schedules before any promos were pressed up. Various reasons have been given for this. Motown didn’t want Earl to be a success, we’re told. Motown deliberately sandbagged Earl’s career, we’re reminded.

But that, to me, is missing the point.

THAT MOTOWN SOUND: CASH REGISTERS

Berry Gordy has been called many things, but if you were asked to name the one adjective even his friends would readily agree to, that word would surely be ruthless.

An accepted narrative has grown up around the Funk Brothers, a kind of legendary glow stoked by the book and movie Standing In The Shadows Of Motown, and it’s a narrative I’m faintly uncomfortable with. We went over most of this when talking about Soul Stomp, but in a nutshell… while not wanting to do down the musicians’ incredible achievements, while not bemoaning their belated (too late) fame, and while not disputing they (along with many others) got a raw deal at Motown, I nonetheless get annoyed when people seem to suggest the Funk Brothers’ light was held under a bushel. “What a shame it is we never got to hear their true genius let free to roam”, or something along those lines. “If only…”

For a start, it’s wrong to say they never got to play off the leash (as we’ll see in a few months’ time). But more importantly, that argument, to me, seems to lead to the conclusion that Earl and the Funks could have been really good, if only they hadn’t been held back by having to do all that Motown pop chart stuff. Balls, says I. Van Dyke, Jamerson, Willis, Benjamin, Messina, White, Brokensha and the rest were legends alright, and I’m glad they’re getting their long-deserved, long-overdue props, but they’re legends because of what they did, not what they might have done. The most successful band of all time in terms of hit records, they were also the greatest band of all time in terms of what’s ON those records. What they actually left us is amazing, and to suggest it only represents a fraction of their true ability is to suggest pop music can’t truly be compared to “real”, serious jazz and classical work – an insult to Motown and those who continue to love it.

But it’s a red herring in any case. Maybe it might have been good to hear some “real” Funk Brothers albums (if only alongside, not instead of, their regular Motown work), but frankly there are other underexposed Sixties jazz-blues records more deserving of your money and attention, records by men and women who didn’t also rack up thirty Number One singles in their sneered-upon “day jobs”. But it might also have been a tedious exercise. Or, it might just have been that we got to hear some more good records, on a par with some of the other interesting stuff that’s come out of the Motown vaults in the CD era.

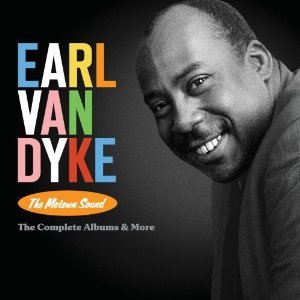

(Case in point: James Jamerson’s got three “solo” tracks included on the new Earl Van Dyke The Motown Sound compilation CD, pictured above. They’re very good. (The best of them, Greedy Green, sounds like “Tighten Up” by Archie Bell & the Drells recorded two years early). They’ve also been available for months now; how many articles have you seen praising them as great lost Motown hits? How many journalists have fallen over themselves to proclaim Jamerson, the greatest bassist of all time, as a visionary solo artist?)

Contrary to popular opinion, it’s my belief that – within certain limits – Motown would have been delighted if Earl Van Dyke had scored a big hit single, allowing him to become a “name”, if not necessarily a star.

Contrary to popular opinion, it’s my belief that – within certain limits – Motown would have been delighted if Earl Van Dyke had scored a big hit single, allowing him to become a “name”, if not necessarily a star.

Sure, he’d have been missed in the studio if he was out on tour, but then that happened anyway – Motown set him up as head of “The Earl Van Dyke Sextet” (not “The Soul Brothers”, or “The Motown Band” or whatever, telling in itself) and sent him out to tour Europe as part of the Tamla Motown launch celebrations, meaning he was away from Hitsville for an extended period of time in 1965 in any case, and yet Motown recorded more studio hours of tape that year than ever before.

Sure, it might have been more difficult to work with him if he was famous in his own right, harder for Norman Whitfield to demand he run through fifteen takes of some obscure B-side fodder intended for the bin – but not much harder; Earl was a seasoned pro, and unlike Choker Campbell (who walked out on Motown in a row over his lack of releases), the only problems Van Dyke ever caused revolved around money. So long as he was being paid, then – like Booker T. and the MGs over at Stax, who’d had a Top Five hit with Green Onions three years ago but still showed up for work – he’d have been fine.

Sure, he’d have been able to demand more things (money, concessions over material, a share of the marketing budget) as a name artist – but then he’d only got to record anything at all because his importance meant he had Motown over a barrel in the first place, and his having a hit record wouldn’t have made his demands any harder to deny.

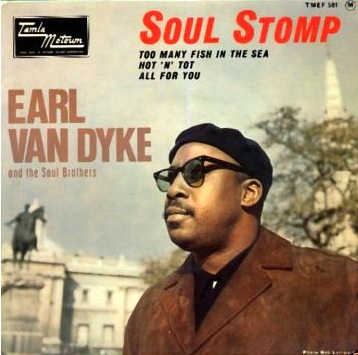

Sure, Motown usually liked to keep the musicians (and backing singers, and writers, and producers) anonymous – but Earl himself was already an exception, billed as a solo artist (instead of, again, “The Soul Brothers” or “The Motown Band” or whatever) – and, in Europe, given a lavish picture sleeve (above), Earl standing in front of Buckingham Palace with his name blown up in giant 50-point type. Are these really the actions of a label actively trying to hobble a man’s ambitions to keep him in his place?

No, for me it doesn’t all add up. Motown had the power and the opportunity to keep him under wraps just like, say, Joe Messina, or Uriel Jones, or Dave Hamilton. If you listen to Carol Kaye or Robert Dobyne (NB: do not listen to Carol Kaye or Robert Dobyne), Motown was so good at keeping its underpaid worker bees out of the public eye that we still don’t know the full story as to who really did what. They let Earl try his hand at making the big time, given the exact same roll of the dice, and – more importantly – subject to the exact same restrictions, limitations and second-hand material as the rest of what Gladys Knight called Motown’s “peon crowd”, the recording acts who weren’t already stars. If he wanted a shot, he’d damn well better toe the line, dance to Gordy’s tune, just like every other artist.

And toe the line he did. So he didn’t get to record a lot of jazz or blues? Neither did the next twenty singers and vocal groups who wanted to be doing that, rather than overdubbing old Mary Wells tracks or working their way through the Jobete catalogue for the benefit of a barely-interested third-string producer. They all did it for as long as they could stand it, and Earl did it too. (While being paid rather more than many acts on the roster, to boot.) Could he have been a contender? Hell, anyone could have been a contender if Motown had thrown their entire weight behind them; and Motown hardly ever threw their entire weight behind anyone, and them’s just the breaks.

ALL FOR WHOM, EXACTLY?

So why was this cancelled? Why did this come out in Europe, and not in America?

It’s really simple. There are two reasons. One: while most of the cuts on Earl’s proposed That Motown Sound album were well-known singles by other Motown acts, the original vocal versions of Lucky Lucky Me ended up being shelved, and so US audiences wouldn’t have known what this was. European audiences, by contrast, were almost entirely new to Motown in general, and Europe had a proud history of embracing black instrumental music. When it was announced the Earl Van Dyke Sextet would be joining Tamla Motown’s package tour, it made sense to dust something off and issue it as an accompanying single, and All For You was ready to roll.

The other reason is simple too: it’s just not all that great. It’s not bad or anything, but nobody will be listening to the nine sides we’ve covered from 1965 to date and picking this one out as the killer cut. It just doesn’t make a real impact, especially not when put alongside Junior Walker’s explosive Shotgun, or some of Stevie Wonder’s contemporary singles; Motown USA just didn’t have room to market their third-best instrumental act.

I love Earl’s playing, but his greatest strength was always the energy and attack he brought to a band performance; it was never solos, and certainly not lengthy, exposed solos like these, almost following the line a saxophone would take when replacing a lead vocal. The results are almost universally disappointing, as well as instantly dated, the blinding light and aggressive cool of the original tracks diminished by Van Dyke’s jaunty, parping style on lead organ.

That’s especially noticeable on a track like All For You, which (as Lucky Lucky Me) would surely have been a huge hit in the hands of either Marvin Gaye or (my favourite, somehow even better) Jimmy Ruffin. There’s not one of Earl’s organ overdubs where I come away thinking the result is better than the original, and this one definitely isn’t; not for the last time, Earl turns in what turns out to be the weakest of several competing Motown versions of the same song.

But it’s probably worth remembering at this point that nobody (apart from collectors, bootleggers and other nerds) heard Lucky Lucky Me, in any version, until thirty or forty years later. Instead, most people’s only exposure to this song, this track, was via Earl’s version, and this (along with an alternate re-recording released in Britain in 1970) is the only time here on Motown Junkies we’ll meet this song, and so (bizarrely) we’re not judging Earl’s version as a cover, but as the original.

Van Dyke’s lead organ is the weakest thing on here; he’s proficient enough, but (as with Junior Walker on Hot Cha) there’s a difference between “difficult” and “worthwhile”. But the track he sets about ruining is one of Motown’s most criminally overlooked, a track Earl himself helped build. The whole thing is a locked-in drum and bass groove, powered along by a bed of cooing backing vocals and hammered piano, before some quite superb funk guitar work and a big, rousing key change two-thirds of the way through, all culminating in a chant of HEY! at the end of each chorus before the drums and bass kick in again. It works just fine without the lead vocals on it, even if we already know how much better it could be with them.

But the decision to splice Earl’s lead organ line onto the track is a complete misjudgement, an unnecessary extra ingredient nobody was asking for. Earl did at least two takes, the single version presented here and another version included on the That Motown Sound LP, which Tamla Motown eventually issued as a single in 1970; they’re both semi-improvised, Van Dyke keen to use the session as a starting point for a lengthy jazz organ jam. There are a few nice moments of frantic fingerwork and loud, high sustain parts, but on the whole, it only serves to distract and detract from the excellent backing track the band had already completed. The eventual effect is wearying, and ends up only serving to diminish the power of the song, a smashing groove turned into a pleasant but inessential curio.

Overall? It’s alright, but the organ is annoying, and it mainly serves as a reminder of Motown’s foolishness in not issuing one of the vocal versions instead. But hey, at least it let me talk a lot, right?

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in Earl Van Dyke or the Funk Brothers? Click for more.)

|

|

| Jr. Walker & the All Stars “Hot Cha” |

Earl Van Dyke & the Soul Brothers “Too Many Fish In The Sea” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

I have to agree with your analysis here. I have never really taken to any of the Earl Van Dyke instrumental releases. The backing tracks are great but when the organ kicks in, the track is relagated to a poor rendition of something you would expect to hear in the Blackpool Tower ballroom in the 60’s. Van Dyke was extremely tallented but none of his releases do him any justice but at least releases like this brought him into the public eye unlike many of the musicians playing on them.

LikeLike

Yep, that’s it in a nutshell. It’s not that Van Dyke was bad, it’s that organ renditions of pop hits are just a bad idea. The Blackpool Tower reference is spot-on, and probably explains why I shudder at the very sound of some of these, like I’m a bored child again waiting for an interminable Come Dancing special to finish so I can use the record player. I wonder if American readers have an equivalent.

LikeLike

How you can compare Earl Van Dyke with Reginald Dixon is beyond me. If anything coming out of the Blackpool Tower had 1/10th of the excitement and power of this recording I’d be amazed.

LikeLike

I liked the analogy so much I used it in another review, so you can direct some of that flak my way 🙂

It’s about the actual sound of the organ (something to do with the drawbars, as we found out on another comments thread), rather than the excitement and power, never mind what it’s being used to play – indeed, it’s the sound that detracts from the excitement and power. Which is a fault in me and John W up there, not Earl, I know, but there we are. Though props for knowing the name of Reginald Dixon, I’d never have thought to look that up.

LikeLike

Sounds more than a bit like “Pride and Joy,” doesn’t it?…

LikeLike

Just a tad. More so in this instrumental version than in the vocal cuts, actually, now I come to think about it.

LikeLike

You really hit the nail on the head with that second section: That Motown Sound: Cash Registers. I’m totally with you on the way the Funk Bros have been portrayed since Standing In The Shadows Of Motown.

Their accomplishments on the singles put them at the pinnacle of music from the 1960s. They, as a group, had one of the most identifiable sounds of all, especially when you take into account their moonlighting tracks. I can remember the first time I heard Agent Double O Soul on the radio I was convinced it was a Motown record. Was surprised when I got it that it was on some weird label called Ric-Tic. Same with Hungry For Love. I was convinced Ric Tic was a Motown subsidiary. Looks like I was sort of right.

But the Earl Van Dyke records were a bit of a disappointment. Not terrible but not anything to spend a lot of money on (which I did in the 1980s when I found a copy of That Motown Sound). I was convinced I was finding a holy grail but alas……

LikeLike

I’ll agree that The Funk Brothers’ moonlighting work sounds similar in some ways to their Motown recordings. But, in almost all their moonlighting recordings, I also hear big differences from their Motown recordings. Their work on most of The Golden World/Ric Tic/Wingate and Revilot/Solid Hit/Groovesville, and Groove City, and other Detroit labels for whom they recorded sounds less “full” (more hollow) to me than their Motown recordings. Very few of their non-Motown Detroit recordings made me think they might be Motown recordings. I can list those few by counting on my fingers (“Me Without You”-Mary Wells, “My World Is On Fire”-Jimmy Mack, “Poor Unfortunate Me”-J.J. Barnes, “Lucky To Be Loved By You”-Emanuel Lasky, “No Part Time Love For Me”-Martha Star, “That Was My Girl”-Parliaments).

Actually, it sounded to me as if The Funk Brothers/other Motown session players arranged by Joe Hunter and Mike Terry at Golden World Studios while Golden World/Ric Tic were operating, had a much different sound from that produced by Motown AFTER they took over that same studio (and made it their own “Studio B”). I felt the same way about Thelma Records’ recordings. They all had a similar sound to each other, even though they were produced by Don Davis (who also produced at Golden World and Solid Hitbound (Revilot/Groovesville)-which was different from Motown, and different from Golden World. I thought that Correc-Tone Records also had their “OWN” sound, even though they used more or less the same session players as Solid Hitbound, Golden World, and the other “off-Motown” labels, and also many of the main players Motown used. Some of that difference in sound resulted from the different acoustics of the different recording studios, other differences resulted from the different arrangers and songwriters, some from the different desires of the producers and singers. But, I think that a LOT had to do with the sound engineers at Motown. They had found a way to meet Berry Gordy’s request for a full sound that would sound great coming out of car radio speakers, and it seems that that full sound with really well-blended smooth mixes was rarely, if ever, re-created, even by the same producers and recording session players in other studios.

I’d bet that ex-Motown sound engineer, Mike McLean could probably tell us why that was so. But, I’d bet that technical discussion might be boring to most of us, and likely go well “over our heads”.

To me, the sound engineers and The Funk Brothers and other Motown recording session players and their fantastic songwriting staff and producers were the primary reason why their recording quality was so much better than that of most of the other companies, and the singers were only secondary. Certainly, Motown had a lot of great singers. But so did a lot of other companies.

LikeLike

Robb,

Always an interesting and informative response from you. I know a couple of records on your list and I’m going to see if I can find some of the others. I know I said when I first heard Agent Double-O Soul and Hungry For Love I was convinced they were Motown records. But that was way back (I was probably 12 or 13) and even after I bought them and played them I still felt they sounded like real Detroit-Motown records.

I recently picked up a couple of Ric-Tic compilations and listening to them now I agree with most of what you say, they do sound less full and “hollow”. Sort of second string Motown (albeit still enjoyable to me). I wasn’t sure whether it was because the comps I picked up were “gray area” types and not as good sounding as they could be. But I’d still add the Edwin Starr track to your list. That still sounds like pure Motown to me.

LikeLike

I agree with everything that you say but I just want to underline that for me, what really is unpleasant, is the organ. It reminds me of a suburban ice-skating rink, not the great music of Motown.

LikeLike

Absolutely. Not being American, I wonder if “suburban ice-skating rink” is the equivalent to John W’s “Blackpool Tower ballroom” above?

LikeLike

Nixon–another Mel-O-Dy is coming up after this..try to be kind to this one..it’s actually bettter than the Crocket 45s

LikeLike

It’s already been written and queued up, so you’ll have to wait and find out…

LikeLike

I won’t get into a Stax/Motown argument (I hate them, they always ignore the other centers of R&B), however this is one point I give to Stax. It wasn’t just that Booker T. and the MGs were promoted as an instrumental group and given featured spots on Stax tours, but the members also wrote most of their hits.

I’ll also take Jones over Van Dyke on organ.

LikeLike

Quite agree with you on the whole Stax/Motown arguments. For one thing, you have to eliminate people like Aretha Franklin & Wilson Pickett who never recorded for Stax. And then of course there is the whole Chicago/Philly sound plus countless smaller labels to be take into consideration. I’d say just enjoy the music. If there is something you don’t care for, then don’t listen to it. I’ve expressed some other thoughts on the Stax/Motown debate in other areas on this site. I will say that IMHO, Al Green (who I realize recorded for neither Stax nor Motown) may be the missing link between the 2 labels’ music. His music seems to contain strong elements of each sound. Cheers!

LikeLike

I don’t recognise ANY Motown Sound in Al Green’s work-EVEN in “Back Up Train”, which was recorded under the auspices of Palmer James, in Detroit.

I thought that Wilson Pickett was sent by Atlantic records to Memphis to record a lot of his Atlantic-released recordings with Stax’s house band and by their producers. If so, that would make it reasonable to put him on the Stax side, in comparing Stax to Motown. I thought that Aretha Franklin recorded a lot of her Atlantic material at Muscle shoals, Alabama. -which would be the Fame Studios’ band and producers, rather than Stax. But, I also remember that she recorded, at least a few recording at Stax’s studios (is that not so?).

J.J. Barnes recorded at Motown, and Don Davis also signed him to Stax. But, I believe that all his Stax-released recordings were produced by Davis in Detroit (even “Snowflakes”, his Volt Records release. Of course, JJ’s “Rare Stamps” album cuts were all recorded in Detroit by Don Davis, and later, leased to Stax.

Davis brought several Detroit artists (who had previously been recorded using several Funk Brothers and other Motown instrumental session players for records released on Davis-related Detroit labels) to Stax/Volt (Darell Banks, J.J. Barnes, Dramatics, Roz Ryan, Reggie Milner, etc.). And, he also brought “The Detroit Sound” to Stax, including “Detroitlike strings” to the regular Stax artists’ recordings (Carla Thomas, William Bell, Johnnie Taylor, etc.)

Major Lance had also recorded for both Motown and Stax.

LikeLike

Aretha never recorded at Stax’ studios. Jerry Wexler WANTED her to, but by the time she got to Atlantic Stax was too busy with their own artists to take any more outside talent.

I think the only things she cut at FAME were “I Never Loved a Man” and the basic track of “Do Right Woman.” Her then-husband, Ted White, got into it with one of the musicians, and owner Rick Hall kicked them and Wexler out. “Do Right Woman” was completed at Atlantic in NYC, with a piano that was slightly above the pitch of FAME’s instruments. Wexler imported the AL musicians to NYC to complete her first Atlantic LP, including “Respect.”

Wexler seemed to be trying to corner the market on Southern soul: in addition to Stax and FAME, there were deals with Chips Moman’s American Recording studios (Stax’ rivals in Memphis and the future base of Elvis’ comeback), and Buddy Killen’s Dial in TX. All had a horn-and-guitar sound that could be called an “Atlantic sound.”

LikeLike

Wasn’t Al Green’s releases on Motown simply a buyout of Hi records? That’s what I took it to be.

LikeLike

BY the way–for those who don’t own any of the box sets–you can hear them all on SPOTIFY

LikeLike

Rdio also has them if you’re in a non-Spotify territory, though coverage can be hit and miss (Volume 5 seems to mysteriously disappear on a regular basis).

LikeLike

Good info there Randy! I understand that Wexler almost signed Aretha as a Stax artist. Wonder how that would have gone. Yeah, I guess that if we have to debate the whole Stax/Motown thing we might want to say “Southern Soul” vs Motown. It doesn’t matter much to me – To me it is all good music! FYI – you mentioned Elvis. I heard that he cut a few things at Stax in the mid-70s. Don’t think they ever got released. Also, that is interesting about “Do Right Woman” with the piano being pitched slightly higher. I always that that record had an interesting sound to it.

LikeLike

Brother Jack Mcduff? Oh man, you’re killing me here!

LikeLike

Back in the early sixties I ran the Tamla/Motown appreciation society in Australia. Berry Gordy Jr assigned Dave Godin as my mentor as I was only 14 years old. Amongst one of the long lost promotional sheets that Motown sent to me in those early days was a history sheet. As I recall it stated ” Mr Gordy believes that as the sound of Detroit broke down barriers and reached new audiences, those audiences would become more sophisticated and develop an appetite for Jazz”. Remember that Gordy had run a Jazz record shop unsuccesfully before he created Motown. I suspect that a Jazz success possibility was discussed with the session guys and that the “Workshop” label was intended to be the outlet. As the possibility of a Jazz popularity diluted, incredible wealth and demand for “Soul” music dissuaded Gordy from that path. History shows that a dream of popular acceptance of Jazz was misguided.

LikeLike

Oh man – this is one of the most fascinating and thought-provoking of your reviews – and that’s saying a lot.

It’s pragmatic, but artistically bankrupt, to overdub the organ over existing tracks, instead of having the band put their heads together and work out an interactive arrangement and thus have an opportunity to be as good or much better than Booker T. & Co. Can you imagine if they’d combined the harmonic innovations of HDH with their own rhythm section innovations? Imagine something like Green Onions with the harmonic magic of Baby I Need Your Lovin’ or Stop in the Name of Love. And imagine the subtle magic in the drums and bass that would have graced these grooves if Jamerson & Co. were hearing the organ lead as they re-recorded them.

And Berry Gordy – are we sure he isn’t a fictional character written by George R. R. Martin? What shades of grey! He’s a hero for providing the environment for all this great music – a visionary in terms of recognition of talent if nothing else – and a cultural icon for breaking down racial barriers. But the flip side is that he’s just as callous, nearly as unethical and … your adjective is best: every bit as ruthless … as the white record company robber barons whose legions he played such a seminal role in integrating. Gordy epitomizes the best and worst aspects of capitalism. It’s amazing that so much transcendent music resulted from such a shameless “cash register”-dominated approach. In many ways the Stax phenomenon was more of a “feel good story”, growing more organically from a pure love for the music, but while Motown put out hundreds of sides far below Stax standards, most of the highest highs soared up out of the bizarre environment that Gordy created and maintained.

LikeLike

“Earl is just so talented that I for one just cannot wait for him to cut his first solo album. His playing on organ is so controlled and so cool and groovy that I rate him with names like Booker T. and Dee Dee Ford; that much under-rated female organist. Certainly All For You will forever be associated in my mind with the heart warming tour we have just seen, but apart from any nostalgic value it is a fine disc in its own right, with enough of a keen edge of a jazz feel that makes a blues theme vibrate and shimmer. 4/5

“Flip, of course, is a hardy perennial favourite. Not as good as our Marvelettes, but then the original is always the best. Interesting though. 3/5”

[Dave Godin, Hitsville U.S.A. 4, 1965

LikeLike

Dave Godin didn’t mince his words

LikeLike