Tags

Soul S 35018 (A), November 1965

Soul S 35018 (A), November 1965

b/w The Flick (Part 1)

(Written by James Jamerson, Earl Van Dyke and Robert White)

Regular readers will know by now that there are few things I like more than a narrative. Individually, the Motown singles catalogue is just a huge pile of great records (and a few not-so-great ones), but going through them in order like this reveals certain story strands running through that history, strands which are fun to pick up from where we left off last time.

Regular readers will know by now that there are few things I like more than a narrative. Individually, the Motown singles catalogue is just a huge pile of great records (and a few not-so-great ones), but going through them in order like this reveals certain story strands running through that history, strands which are fun to pick up from where we left off last time.

What’s especially fun (for me, anyway!) is where I come across a narrative that’s already in place – but where the records themselves don’t seem to fit the pre-arranged story arc. Earl Van Dyke, Motown’s studio keyboardist, leader of the Hitsville house band, the legendary Funk Brothers, and (largely) unsung hero, is a prime example – and The Flick is a key record in telling the real story.

IN NOMINE

The clue’s in the name.

The Funk Brothers spent much of the Sixties and Seventies in relative obscurity, the faceless but vital cogs in the Motown hit-making machinery, nowadays famous (too late) for having featured on dozens and dozens of big hits, while nobody knew their names; the very title of the Standing In The Shadows Of Motown documentary plays to this. And certainly, there’s a lot of truth to that, all-time greats like drummer Benny Benjamin, bassist James Jamerson and even Van Dyke himself dying in obscurity before the band members belatedly got the recognition they were always due.

But it’s not the whole story, or rather it’s not the only thing in the story – as we discussed when talking about Tammi Terrell, there’s always the potential (especially in hindsight) for someone’s ultimate victimhood to overshadow their actual achievements, or obscure what actually went down before. And so it is with the story of the Funk Brothers.

The story as it’s usually told is pretty straightforward. Motown wanted to keep this tight unit of highly proficient jazz musicians toiling away, and so made a bad-faith promise that they’d be allowed to record their own material if they’d only toe the line. The musicians themselves thought the R&B pop stuff they were pumping out was, to use Van Dyke’s own words, “crap… just the best way to pay the rent”, sales in the millions notwithstanding, and so they waited eagerly for the day they could cut loose on that promised record of their own, to finally show off their chops to the nation with the training wheels off. When the time came to cut an actual Funk Brothers LP, so the story always goes, the company presented the unimpressed band with a load of their own pre-recorded backing tracks, Van Dyke overdubbing a new organ line over the top to substitute for the original vocals, with varying (but generally underwhelming) results.

The story as it’s usually told is pretty straightforward. Motown wanted to keep this tight unit of highly proficient jazz musicians toiling away, and so made a bad-faith promise that they’d be allowed to record their own material if they’d only toe the line. The musicians themselves thought the R&B pop stuff they were pumping out was, to use Van Dyke’s own words, “crap… just the best way to pay the rent”, sales in the millions notwithstanding, and so they waited eagerly for the day they could cut loose on that promised record of their own, to finally show off their chops to the nation with the training wheels off. When the time came to cut an actual Funk Brothers LP, so the story always goes, the company presented the unimpressed band with a load of their own pre-recorded backing tracks, Van Dyke overdubbing a new organ line over the top to substitute for the original vocals, with varying (but generally underwhelming) results.

That’s the story as it usually goes. But as I’ve said before, there’s a lot wrong with this view of events. First and foremost – for me – is the inherent disrespect to the wonderful music these guys did make. “Oh, if only they’d been allowed off the leash, they could have made something really special” falls apart as an argument when we’re talking about the greatest studio band of all time, whose reputation rests solely on the immortal classic pop and soul records they cut for Motown.

This isn’t some band who could have made it, had they only been given the breaks – they did make it, and spectacularly so, and by and large this blog is the story of that success. To wish away the history of Motown in the Sixties for the benefit of any single artist would be sacrilegious; to treat the musicians differently because, hey, these were musicians, and the implied disrespect to the army of teenage girls and boys who didn’t play instruments or even write their own material, smacks of exactly the kind of double standards I can’t accept.

Moreover, though, the narrative that paints Van Dyke and his fellow musicians as modern-day indentured servants, churning out hits in the darkness, kept under wraps as Motown’s best secret (and many accounts explicitly accuse Motown of having actively worked to stifle the possibility of Van Dyke and co. becoming successful “name” artists in their own right, as such a development might actually have hindered the factory-like day-to-day operations of the Hitsville hit production line)… that narrative is just not supported by the facts, even the ones we’ve seen so far here on Motown Junkies.

And the clue’s in the name. Much has been made of the label-enforced change from “Funk Brothers” to “Soul Brothers” – apparently both because the word funk wasn’t in widespread use (other than as a synonym for an unpleasant smell or a dark mood) and because Berry Gordy apparently worried it might be taken as a cognate of or euphemism for “fuck”. Lest such concerns seem excessively prissy and prudish to our modern ears, we mustn’t forget Motown was not operating in a vacuum; this was a time in America where even white boys couldn’t get away with saying “hell” on the radio, and where every inch of progress for any branch of black culture and black life, every modicum of respect grudgingly granted from the white establishment, had been hard-fought and hard-won, and the fear persisted that those inches could easily be swept back by a careless wrong step. So the Soul Brothers it was.

But observe: Motown didn’t change their name to something like “The Motown Band”, or use pseudonyms – or credit these instrumental cuts to a named (vocal) artist for use on B-sides and to bulk out albums, as some of their contemporaries might have done.

Observe the decision to list Van Dyke’s name on the marquee, singled out ahead of his bandmates (something which, to his credit, he said made him distinctly uncomfortable) – an honour at this stage only granted to Smokey Robinson (on albums) and Martha Reeves (without her surname). It’s difficult not to read that as a move simply reflecting the billing status of Booker T. and the MG’s over at Stax, who were still notching hit singles (another motivation for Motown to release The Flick, but we’ll come to that later), but it’s significant nonetheless.

Observe Van Dyke being sent out to tour Europe as part of the inaugural Tamla-Motown Revue, he and his touring group billed as The Earl Van Dyke Sextet, both for the live shows and the resulting Paris live album – okay, so they were usually bottom of the bill, but even that was above and beyond the bare minimum requirements.

Observe the picture sleeve (right) issued in Europe for Soul Stomp, with Van Dyke’s name in fifty point type and his too-cool face filling the frame.

Observe the picture sleeve (right) issued in Europe for Soul Stomp, with Van Dyke’s name in fifty point type and his too-cool face filling the frame.

No. If anything, Earl Van Dyke had cause to be grateful to Motown for publicising his name as much as they did; it’s the other key players (and it’s Jamerson and Benajmin who come to mind, again) who had more right to feel aggrieved. But then, one might argue, nobody was exactly making sure the public knew the names of all the members of the Miracles or Vandellas either (not to mention the likes of the Velvelettes, Elgins or Monitors).

The shabbiness of Motown’s later treatment of the core of the Sixties line-up of Brothers – especially of James Jamerson, who nowadays would be lionised, flaws and all, but whose time came too soon for an industry which even now has a grubby track record when it comes to looking after its pioneers – can’t be airbrushed out of the story. We can’t, and shouldn’t, pretend Motown come out of this smelling of roses. But to sweepingly declare the Funk Brothers got no support or public recognition at all from Motown is just as incorrect.

FRATRES

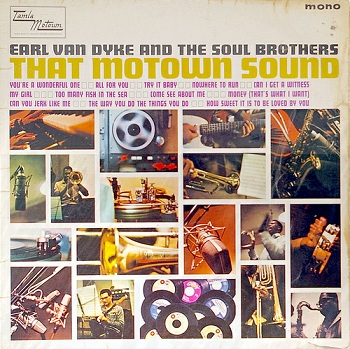

Because, well, then there’s the music itself. Yes, Motown’s offer of an album for the band was a damp squib – That Motown Sound, pictured below, is a ragtag bunch of slightly rum cover versions and I’m no great fan of it, as you’ll have gathered judging by the 45s from those sessions we’ve seen here on Motown Junkies (Too Many Fish In The Sea, I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch), How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You), average score 4 out of 10). But that doesn’t tell the whole story.

For starters, there’s another double standard at work here. Lots of Motown acts never got an album at all. Pretty much everyone who recorded for the company was presented with a bunch of pre-written material and selected covers and told to get on with it, to do as they were told. The Supremes, both the label’s biggest cash cow and arguably the biggest group in America as 1965 drew to a close, were busy ploughing through endless albums of material in the hope of snagging some sales. And Motown, right now, was not really an albums label – even though several superb LPs had appeared for a number of artists, this feels on reflection more like a happy accident, or something which happened despite the company’s attitudes at the time, rather than a concerted effort. The company was still geared around the concept of the album as a glorified EP.

For starters, there’s another double standard at work here. Lots of Motown acts never got an album at all. Pretty much everyone who recorded for the company was presented with a bunch of pre-written material and selected covers and told to get on with it, to do as they were told. The Supremes, both the label’s biggest cash cow and arguably the biggest group in America as 1965 drew to a close, were busy ploughing through endless albums of material in the hope of snagging some sales. And Motown, right now, was not really an albums label – even though several superb LPs had appeared for a number of artists, this feels on reflection more like a happy accident, or something which happened despite the company’s attitudes at the time, rather than a concerted effort. The company was still geared around the concept of the album as a glorified EP.

In that spirit, the musicians getting their album (largely credited to, and dominated by, Van Dyke) has to be seen in the light of how the label treated anyone whose albums weren’t guaranteed to fly off the shelves. Alright, Marvin Gaye was heavily indulged with some MOR vanity projects, but he was very much an exception, and anyway he paid his way with hits; heck, even the Marvelettes, the label’s first hit-scoring artist and still a consistent singles draw, weren’t given an LP release between 1964 and 1967. The Funk Brothers didn’t get a great deal, but as artists they got a better crack at the big time than a lot of their labelmates, and – arguably – better than their individual popularity and commercial viability really merited.

But most importantly of all, the records themselves just don’t support the theory that the Funk Brothers weren’t themselves indulged in some way. Okay, Motown may not have thrown their entire commercial weight behind pushing these sides to radio, but nor did they just let the Brothers’ non-cover records rot on the vine. Even if they had, it’s remarkable enough that such sides existed in the first place: even leaving aside the sort-of-exclusive All For You, still a pop overdub at heart, witness the one-two punch of Soul Stomp and Hot ‘n’ Tot, released (twice!) in Britain at a time when big-ticket hitmakers weren’t seeing regular European action.

Those are, presumably, at least rather closer to what the musicians wanted to do than the parping MOR-jazz of e.g. How Sweet It Is, and if they didn’t completely satisfy Van Dyke and his fellow jazz cats, well, these guys were signed to Motown – the home of perfect pop perfection, where everything went through Quality Control and ended up packaged and sanded and moulded and buffed and shaped. What did the Funk Brothers expect – to just record an impromptu twelve-minute live jam, sounding like it was cut in a rough and ready fug of spilled beer and smoke, and have Motown release it as a single, right in the middle of their most glorious run of R&B-pop masterpieces, right when they’d just cemented their place as the top-selling label in America?

Oh, right. Yes. That is, in fact, exactly what happened.

AND NOW, THE FLICK

The weird thing about The Flick – and yes, Part 2 is the A-side (there are another two parts out there besides the ones on this 45, of which more tomorrow) – is just how much fun it is anyway, how closely the “unleashed” Funks end up hewing to the feel (if not the musical style) of what was happening around them at Hitsville. Recorded live in the studio, apparently as a jam extemporised by three of the band (Van Dyke and Jamerson joined in the writing credits by the legendary guitarist Robert White, he of the immortal opening riff to the Temptations’ My Girl), it’s surely a reasonable inference to draw that we’re hearing the true, unadulterated sound of the Funk Brothers here, the music they themselves wanted to make. In common with the youthful writers, producers and singers whose visions they’d brought to life, it’s teeming with the confidence and enjoyment of the best Motown sides of 1965, despite sounding nothing like them. And it’s fun.

What do you reckon the teenyboppers made of this? I’m not sure, but I don’t think it would have terrified them; it’s a tremendous palette-cleanser and a breath of fresh air between Himalayan peaks of pop majesty. And it’s a kind of pop in itself – built around a five-note growling loop of Jamerson bass, with other ingredients gradually layering over the top and playfully pitting themselves against each other, it’s a jazz record first and foremost, but a very accessible one.

That bass loop is easy to latch onto (one suspects easier now, for our post-disco, post-electro sensibilities and our recalibrated sense of what pop records do, than in 1965), and when the foot-stomps are replaced and the clattering, echoing drumbeats instead start bouncing down the stairs, you can practically hear a thousand future hip hop stars prick up their ears.

Really once again the wild card is Van Dyke himself, his organ the most dated thing here – but unlike most of the records billed to his name, he’s not the weak link, he’s an electrifying presence, his keyboard squalls a kind of audience avatar, squeezing his way into the ring and then spurring the titans of drums and bass on, egging them into a duel, whipping up the frenzy of the crowd. Us, I mean, not the actual crowd that’s audible here (they were apparently dubbed on later in a bid to give this more fizz, and it worked).

I wouldn’t want to have a whole LP of this, but the label seemingly felt the same way, Motown wisely chopping it down to two manageable 7″ chunks, this one the more energetic and enthralling. It’s like a snowplough, or a slow-moving train; turn it up and then get the hell out of the way, because it will come right through. We are the Funk Brothers, and when Motown isn’t making us jump through hoops, this is what we do. It’s a fragment, a tiny clip of something glimpsed through a window that’s opened just a crack and will soon be safely shuttered back up again, but it’s enough to humanise the musicians more than any other record before or since; this one, we feel, is theirs.

So, yeah, it’s cool alright. Is it as cool as Don’t Mess With Bill? I don’t think it is; I know I’ve cited this quote before, but once again I’m put in mind of the Boo Radleys’ Martin Carr and his remark about incorporating avant-garde influences into pop records: it doesn’t mean watered-down avant-garde, it means more sophisticated pop. And, ultimately, that’s what Motown and the Funk Brothers gave us from their day jobs: cutting edge pop music. Brilliant pop music. That these guys were allowed to let off steam and show off their true chops once in a while, display the workings behind some of those incredible pop records, made perfect sense – and it shouldn’t be forgotten those opportunities did once come along – but it doesn’t invalidate the merit of the finished product.

Still, could it have been a hit? Bizarrely, yes, I think it theoretically could – or, at least (and probably more importantly), I can see how Motown might have thought it theoretically could. Remember, this is still a world where Fingertips had scaled the very top of the charts, where both the aforementioned Booker T. & the MG’s and the Funk Brothers’ Soul Records labelmates Junior Walker and the All Stars were racking up Top Tens, and so this doesn’t read as a sop to the musicians, but rather a “meh, what the hell, why not?” gesture on Motown’s part, the label never shy about chasing money wherever it was to be found and potentially scenting some here.

Was this the band’s big chance? As far as Motown singles were concerned, probably, yeah – we won’t be seeing another Van Dyke/Funk Brothers release for over a year, and even that might be seen as an exception to the normal rule. Motown often displayed loyalty to those artists who had served their apprenticeships on vinyl before the label hit the big time, but they had no room for commercial failures; the musicians’ years of service and vital contributions to so many hits might have been expected to carry weight, but then that was never the Motown way. If you weren’t having hits, you weren’t going to get a lot of singles, no matter how many hours you’d logged at the coalface.

(Heck, look at the producers – Lamont Dozier got one single, Hal Davis got one single, Ivy Jo Hunter got two (eventually, grudgingly). The behind-the-scenes stuff entitled you to no more than a shot at a shot, and sometimes not even that much – the likes of Norman Whitfield and Brian Holland, who between them made millions of dollars for the company, and who both became performers of a sort after leaving, got no artist credits at all.)

But the real surprise about The Flick is that it exists at all, given we’re constantly being told it doesn’t. Don’t believe a word of it. Play it, and thrill to it, and reflect on the men who made it – but excellent though this is, if you seek the true monument to the greatness of the Funk Brothers, it’s already all around you every time you turn on the radio. These guys built Motown. This is how they rolled.

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in Earl Van Dyke or the Funk Brothers? Click for more.)

|

|

| The Marvelettes “Anything You Wanna Do” |

Earl Van Dyke & the Soul Brothers “The Flick (Part 1)” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

Ooh, it’s been a while since I’ve written anything really long like that 🙂 Hope it was worth the wait, even if you don’t agree with my reasoning or conclusions.

LikeLike

Just placed a comment here:

referencing remarks made about Earl Van Dyke.

LikeLike

Referencing remarks made about the Funk Brothers’ version of “Sugar Pie Honey Bunch”, to be precise. And calling me out for being too young to talk about this stuff.

LikeLike

I did not “call you out”. I merely said I don’t know whether you are old enough to have been around when certain events took place. 😉

LikeLike

Well, now you know I’m not! 🙂 I’m an ’80s kid. How that influences your subsequent view of this place and what I’m doing, I’ll leave that to you…

But I was more concerned that your description (“remarks made about Earl Van Dyke”) made it sound as though I was having a pop at Earl himself, which was emphatically not the case. For the avoidance of doubt, I have nothing but respect for Earl Van Dyke (a legend and all-round great guy, as I’ve said elsewhere); that doesn’t mean I’m going to give unqualified praise to everything he does. If it’s reverence you’re after, you’re in decidedly the wrong place 🙂

LikeLike

It was worth the wait. It is always worth the wait with you. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s very much not, but thank you for saying so anyway.

LikeLike

A veritable powerhouse of a sound. Although almost devoid of any real melody this is still an incredibly enjoyable listen. The rhythm is quite amazing and uniquely structured. A somewhat specialist piece as it has virtually no commercial appeal. No wonder it was not selected for release in the UK. I wish Junior Walker had cut this using the same backing track but with Junior’s sax replacing the organ. The track would have suited Walker to a tee. Not surprising really as it was produced by Gordy/Horn who also produced a lot of Walker’s stuff at that time. I give it 8.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s me again. You may think I just like having a pop at you. Please understand that it not the case. I just feel that you have raised some issues that need addressing.

Here’s the thing.

You talk of the Funk Brothers as a “Motown act” – but in reality, they were not, Yes, some of their output was packaged up and a name created for them, but essentially, we are looking at a number (13, I believe) of paid session musicians.

Now, Motown, first and foremost, made DANCE MUSIC.

So, quite rightly, the best session guys that could be found were hired to play the kind of music that Motown believed would be successful.

Now, like ANY session musician – if fact, like ANY musician – those guys would have had their own personal tastes. And yes, a lot of musicians, because of the “freedom” it gives them, like to play Jazz.

But the skill of a good session man is being able to play ANY kind of music that they are asked to play. This was not something weird foisted on the Funk Brothers by Motown. It was (and is) standard practice in a Recording Studio.

I know that, years later, some of those guys have complained about their treatment at Motown (a lot of vocalists have said the same), and Earl apparently made his remark about “crap” (which, if he did, was a crass thing to say). But let’s not try to rewrite history over something that is standard practice in the Music Industry.

You seem to be making the point (or at least, that it how it reads, to me) that because they liked jazz, but were somehow forced to play DANCE MUSIC through gritted teeth, that some of their output is therefore worthless.

This track, for example, gets a higher mark, due to its perceived “jazzness”, than some of their classic grooves that made Motown’s fortune. Only the inclusion of vocals raises the votes.

So how does that work?

You make specific mention (and you and I have discussed it) of “I Can’t Help Myself” – which you deem to be “pointless” without Levi Stubbs in the foreground – as if it is somehow doing disservice to their “jazz” roots, and without vocals, their efforts are not worth listening to.

But wait, Levi was a member of Four Tops, a 50’s Jazz Quartet taken on by Motown to spearhead a move into Jazz with its Workshop label.

So using the logic being applied to the Funk Brothers output, should the output of the Tops be deemed equally “pointless”??

And almost all Motown output consists of 50% backing and 50% vocals – so are ALL the backing tracks made by misplaced jazzmen “pointless”??

I’ve been buying singles since 1958, and one thing that has been pretty much a constant is that popular 45s are largely the product of Songwriters ,Record Producers and (where an orchestra is involved) Musical Arrangers. And session men will have played on the majority of them. And been paid a wage. Nothing more.

One of the most famous session men in the UK, at the same time as the Funk Brothers, was Jimmy Page, who later found his own fame with Led Zeppelin.

Do fans of Petula Clark think “Downtown” is less of a record because the guy playing guitar favoured somewhat different music? Or has Jimmy complained about being “made” to play on it?

For me, it was the likes of Dozier, Holland, Fuqua, Robinson. Bristol – even Whitfield at a push – who made the Motown sound. The grooves they came up with are fabulous. And the guys who played on them did a fabulous job. They are to be congratulated for ALL of it – not just the bits where a vocalist was in the room. Or the bits that the session men preferred.

I know lots of folks who would describe it all as “pointless” and forced.

But the last place I would expect to see that is on a Blog called “Motown Junkies”!

PS. The fact that the Funk Brothers, when not playing in the Snake Pit, moonlighted at other studios, still playing DANCE music, rather than Jazz, does rather dilute their “we wanted to play jazz” protestations.

PPS. I think what you do on here is great. Some excellent reading. But I think trying to be so verbose on something as simple as a two and a half minute pop record can tend to over-intellectualise the whole subject.

When I review a record on my forum, my rule is that if it takes longer to read than it does to listen to the track – then I have written too much. But that’s just me 🙂

LikeLike

Well, with respect, you’re putting words in my mouth, even though my actual words (and lots of them, as you say) are right there above. Your entire post is combating a straw man which could scarcely be more at odds with my actual position – obviously I’ve not been clear, so I’d recommend reading the previous entries on the EVD/Funk Brothers singles, and especially the first one (Soul Stomp), in the hope it clears things up a bit.

First off, here’s Earl’s quote in full (as quoted in the Soul Stomp piece – and there’s no “supposedly” about this, it’s a direct quote lifted from the liner notes to the abovementioned CD compilation), which explains why they supposedly persevered doing what they didn’t like:

““A lot of the time, we thought the stuff we were playing was crap. None of us ever thought that Motown would get that big. All we wanted to do was play jazz, but we all had families, and playing rhythm and blues was the best way to pay the rent.”

Followed by a quote of my own from the same (Soul Stomp) essay:

They may not have liked it, but the Funk Brothers were the best corps of R&B/pop musicians ever assembled, and the “crap” they spent their days turning out was the best collection of R&B/pop records ever released, and that, to me, is worth a thousand critically-acclaimed, little-heard jazz LPs. Dying unknown after achieving so much greatness is a harsh and undeserved fate, but wishing away their magical life’s work isn’t the way to make it right.

And just so we’re clear, let me throw in a couple of quotes from the actual piece above which we’re commenting on, which you seem to have glossed over:

…That’s the story as it usually goes. But as I’ve said before, there’s a lot wrong with this view of events. First and foremost – for me – is the inherent disrespect to the wonderful music these guys did make. “Oh, if only they’d been allowed off the leash, they could have made something really special” falls apart as an argument when we’re talking about the greatest studio band of all time, whose reputation rests solely on the immortal classic pop and soul records they cut for Motown.

…That these guys were allowed to let off steam and show off their true chops once in a while, display the workings behind some of those incredible pop records, made perfect sense – and it shouldn’t be forgotten those opportunities did once come along – but it doesn’t invalidate the merit of the finished product.

I don’t really understand how you get from there to your post, other than railing against the word “pointless” which I’ll come to in a minute.

If I can sum up what I actually think, it might help. These are my contentions:

I like The Flick because I think it’s excellent fun. I don’t like most of the EVD overdubs because – take a breath, I’m going to use that word again – I think they’re pointless, literally, in that I don’t “get” the point of their creation. I mean, I read your comments both above and over on the I Can’t Help Myself thread, and leaving aside the appeal to rarity (which is extra-textual and doesn’t change what I think of the records themselves), I keep coming back to the same line of reasoning: “they’re not pointless, because I and many others like them”.

Alright, yes, that makes a kind of sense (after all, I’m sure almost every record that’s ever been made is someone’s favourite, somewhere, and so by that definition not “pointless”), but that’s not what I’m saying. Rather, I’m saying that – for me – there’s no real reason for them to have been made, because – for me – overall, on balance, they add nothing (and sometimes detract, often significantly) compared to the version that was already a hit.

If you disagree with that last point for any given record I’ve called “pointless”, then yes, they’re not pointless at all, because – unlike me – you’ve heard something new and special in there that you like enough for it to make the exercise worthwhile. For you. That’s what you’re disagreeing with, not a sweeping condemnation of instrumentals or pop music or dance music or whatever else it is that you seem to think I’m against.

Do understand: I’m not saying those overdub records are all bad, I’m not even saying they aren’t enjoyable on their own merits, I just don’t personally ever see myself choosing voluntarily to listen to them over the vocal versions. That’s not to do down the contributions the band already made to those original versions, but here, it’s always been my policy that redundancy (a subjective measure, obviously) costs marks. Not all the marks, and the reverse isn’t true either (I don’t generally praise things just for not being redundant), but it’s a good starting point.

We’ll be coming up on this argument over and over again in the late Sixties as the Jobete catalogue and the pre-recorded band track archive becomes a free-for-all buffet; the covers that will come out with high marks (and here, anything above 5 is doing well) are the ones that add something different, that offer a reason for their existence beyond simply being a rarer alternative to a hit.

I hope that sums it up, anyway.

LikeLike

(Oh yes -and “over-intellectualising the whole subject” is pretty much the motto of this place!)

LikeLike

Hi TNA

Thanx for the reply.

A quick response from me – gotta go out.

One of the points I am making is Yes, the Funk Brothers make the claim about playing “crap” – but their claim is spurious. And poorly argued.

As I said, they simply did what EVERY session man does to this day.

They played what they were asked to, and got paid for it.

And they were happy to do EXACTLY the same for anyone else in Detroit who would pay them. The Jackie Wilson stuff they did for Brunswick is even MORE poppy than Motown.

So the story doesn’t hold water – it just makes good liner notes and documentaries.

But tell a story often enough and some will buy it.

And bizarrely, the “we was robbed” sensibility is now being used on here to justify some very bizarre voting.

One of the posters describes this track as:

“almost devoid of any real melody” and “it has virtually no commercial appeal”, and then gives it an EIGHT!!

Whilst some of there powerhouse grooves (you know the ones I mean 🙂 ) are given 4s and 5s – because the poor old Funk Brothers didn’t enjoy doing them??

I guess the main difference between me and some of you guys, is that I DANCE to Motown, rather than just listen to it. Dancing is what they were made for, in my book.

A powerhouse backing from the Funk Brothers is equally good to dance to, whether someone is singing on it, or not. Sitting on a chair with your headphones on, I guess you might think differently. Hence “pointless”. I guess we will agree to differ 🙂

LikeLike

Hi there soshe, I’m the one who described it as lacking melody and uncommercial then gave it eight. That’s because a recording doesn’t necessary have to be commercial or melodic to be an enjoyable listening experience. It’s whether the finished recording has appeal to a particular individual or not that matters. Let’s face it if a recording has to have some melody to be enjoyable then nobody would like rap or heavy metal as these types of ‘music’ are devoid of melody. Admittedly, if one wants to dance to a recording this might give a different appeal and enjoyment requirement to one who only wants to listen. I’m not a dancer only a listener to music so I can’t comment on the listening appeal of the recording in my opinion.

LikeLike

Hi nafalmat

That’s cool.

As I said, I have always regarded Motown as music designed for dancing. Their slow numbers could do well, but their dancers made their fortune.

The Tops “Baby I Need Your Loving” established them, but only made number 11. The follow up, “I Can’t Help Myself” made number 1 and created an international act.

Because it was a dancer.

I agree with you about rap & heavy metal – that’s why I don’t listen to it.

Any Record Company (like any commercial business) is “addressing a market” when they put a record out. That way, they have more chance of turning a profit. And the market that Motown were addressing in 1965 was black and white teenagers who wanted to dance.

So “The Flick” was a definite fail. I didn’t know Berry Gordy personally, but a good friend of mine (now, sadly, dead) did know him, and from what he told me, I would imagine this was put out purely to fulfil some contractual obligation. It was never intended to be a hit. In fact, it could well have been chosen because they expected it to fail.

So I am still intrigued as to why you gave this a higher mark than their danceable numbers.

If you don’t like dance music, fair enough – each to his own – but as I said before, that is not a view I would expect to see on a Blog about Motown 🙂

LikeLike

Like Nixon, I like this cut because it’s a very good Jazz cut. And I agree with you that Motown never had the slightest intention to sell any Soul Brothers’ records. Otherwise, they’d have given them some marketing push. As I remember, WVON, KGFJ, KDIA, and WDIA ALL played “The Flick”. So, their DJs also agreed with us that it was a great-sounding cut. I also liked The Merced Blue Notes very much.

LikeLike

This is one of the few that i don’t remember hearing. So i got curious and purchased “The Complete Albums”. I do hope it will be worth my while. Oh, while i’m thinking about it, Soshe made reference to “Baby I need Your Loving’ going to #11 and “I Can’t Help Myself” going to #1 because it was a “dancer”. I saw the Tops perform BINYL on the tv show Shivaree and i’m almost sure i saw people dancing.

LikeLike

I don’t think “The Tenny-boppers” had any chance to think anything about “The Flick”, as I doubt that it was ever played on any “Pop” radio station. It was played on US Black Radio, because those stations all still interspersed Jazz cuts into their play lists during the mid and late ’60s, (i.e. “Hole-in-the Wall” by The Packers, “Rufus Jr.” by The Merced Blue Notes, “Listen Here” by Eddie Harris, “Liberation” by The Afro Blues Quintet Plus 1, etc. “The Flick” fit that genre, as did “Cleo’s Back”, by Jr. Walker & The All Stars.

LikeLike