Tags

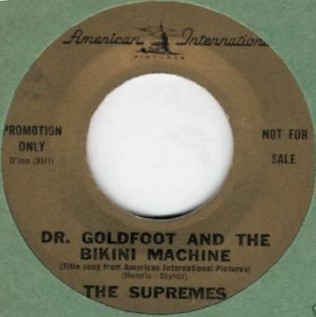

UNRELEASED: promo only

UNRELEASED: promo only

American International (A), November 1965

One-sided promo record

(Written by Guy Hemric and Jerry Styner)

It’s taking us a very, very long time to get through the closing weeks of 1965 here on Motown Junkies, for one reason or another, and I don’t know if the task is made easier or harder knowing that there are still some grand Motown monuments to scale up ahead even before we reach the new year. Certainly the Supremes’ 1965 story has another key chapter for us to investigate even without me adding in extra records to slow us down yet further (this one doesn’t appear on The Complete Motown Singles series, not technically being a Motown single but rather a special appearance single by a Motown artist – but it’s included on the Supremes’ own 50th Anniversary Singles Collection, giving it a dubious pass into the canon).

It’s taking us a very, very long time to get through the closing weeks of 1965 here on Motown Junkies, for one reason or another, and I don’t know if the task is made easier or harder knowing that there are still some grand Motown monuments to scale up ahead even before we reach the new year. Certainly the Supremes’ 1965 story has another key chapter for us to investigate even without me adding in extra records to slow us down yet further (this one doesn’t appear on The Complete Motown Singles series, not technically being a Motown single but rather a special appearance single by a Motown artist – but it’s included on the Supremes’ own 50th Anniversary Singles Collection, giving it a dubious pass into the canon).

All the same, I couldn’t resist including this, as it’s a great opportunity to take stock and observe just how massive and out of control this thing has become. Oh, not the blog, no (although, well, hmm) – no, I mean Motown Records.

The Motown story is the story of an incredible, against-the-odds triumph, commercially and artistically; a tiny black-owned indie label becoming not only the greatest record company of all time (subjective opinion), but also a commercial behemoth (objective fact). Motown, we’re told, somewhat unbelievably, sold more 45rpm singles in America for the year 1965 than any other label; from a standing start, a semi-literate former boxer with no business experience other than a failed record store under his belt took an $800 family loan and a disused photography studio and, within seven years, was on top of the world.

If it sounds hackneyed, it’s because life itself is sometimes hackneyed; this stuff really does happen sometimes, and it happened here. No one Motown artist’s story hews closer to this overall narrative than that of the Supremes, the unloved, ungainly runts of the litter turned flagship act, who’d gone from gawky gum-chewing schoolgirls to elegant global superstars. Whether by accident or design, Berry Gordy could have chosen no better brand ambassadors; not only did they reflect all the values he’d been grasping for, visually and aurally, but they’d done the slog too, fought in the same trenches, been there through the whole journey.

For many people, then and now, the Supremes were Motown, and so it’s both helpful and fitting that their story reflects the story of Motown. And that, in a roundabout way, brings us to this bizarre little artefact.

FRANKENSTEIN’S MOTHER

The Supremes, eh? Fights break out every time they’re mentioned over on Soulful Detroit, catty remarks go flying, music snobs and soul purists turn up their noses, hipsters disdain the group’s avalanche of oldies radio hits. But look, they were brilliant. They were. We’ve been over this many times now. They may not be your favourite Motown act – they’re not mine – but whether or not you agree with me on their brilliance, I posit that there’s little to be gained through pointless iconoclasm, complaining their singles weren’t as good as [INSERT NAME OF RANDOM LITTLE-HEARD DEMO OF YOUR CHOICE], and therefore dismissing them, throwing out the baby with the bathwater in the process.

For me, the keys to Motown’s true greatness are threefold: depth, breadth and quality. Depth, because however deep you dig in the catalogue the quality threshold seems to stay absurdly high – from mega-hits to more obscure A-sides to B-sides to album cuts to unreleased material, the reason I’m able to do my radio show without repeating a single track (27 hours so far!) is because there’s seemingly gold all the way down. Breadth, because as this website surely attests, for all the stereotypical jibes about production line pop, Motown was an incredibly broad church, finding room to have Give God A Chance cheek-by-jowl with Satan’s Blues and both of them sharing studio time with My Girl and Baby I Need Your Loving. The Supremes represent just one part of that, and how representative they really were depends largely on each listener’s own personal response. Finally, quality, because so many of these songs are superb, timeless, classic, whatever other shopworn adjectives you want to label them with.

That the Supremes should become the figureheads for all of this, so widely seen as the quintessential Motown group, might rankle with those who prefer a little less sugar in their coffee – but how often does your favourite politician run for President? Would you rather have the Supremes at Number One, or The Ballad of the Green Berets? And if you don’t care about sales and charts and magazine covers, then what does it matter? Shouldn’t the Supremes be afforded grudging thanks even from those who’ll never voluntarily listen to one of their records, for giving Motown the financial freedom to sign and release pretty much whoever they wanted, effectively bankrolling any number of obscure Motown soul sides? For at least helping to kick in some doors that had hitherto remained firmly closed to black faces?

It’s easy for me to say “the Supremes were probably the biggest group in America” and for it to mean nothing. But their civil rights PSA, and their appearance on the front cover of Time, and their landmark show at the Copa, and their millions of records sold, and their being the first female group to top the US album charts right on the heels of Beatlemania and the British Invasion… all of this provides some context. How many Sixties pop groups, male or female, black or white, signed a marketing deal to put their logo on bread?

It’s easy for me to say “the Supremes were probably the biggest group in America” and for it to mean nothing. But their civil rights PSA, and their appearance on the front cover of Time, and their landmark show at the Copa, and their millions of records sold, and their being the first female group to top the US album charts right on the heels of Beatlemania and the British Invasion… all of this provides some context. How many Sixties pop groups, male or female, black or white, signed a marketing deal to put their logo on bread?

But what sort of America had they, and Motown, emerged into? The world had changed, there’s no doubting it. Think of Fifties America and the Eisenhower administration, and – for those who weren’t there – the whole decade seems somehow to have taken place in black and white (and in terms of the media portrayals that reached us here in Britain via TV and bad movies, rather more white than black).

Not so much the Sixties, and that’s an example of how even the best laid plans can go awry. There’s no doubt that back in 1957, Berry Gordy would have been planning even then to take over the showbiz world as he watched a song he’d co-written climb the charts in the hands of Jackie Wilson – but while the 1957 Berry would surely not have doubted you if you’d told him he’d be sitting atop a multi-million dollar music empire in eight years’ time, surely neither he nor anyone else could have conceived of the music industry he’d actually conquer. Only eight years had passed since Reet Petite, and yet in some ways it feels like two or three times that long, not least because – in mind-bending fashion – of the musical and social influence of Motown themselves. They had put a sophisticated potion of R&B, rock, jazz and pop into the commercial mainstream, and they’d done it with black talent as the public face of a black-owned business, and they’d done it not by pandering to white audiences but by attracting them.

In 1965, the contradictions between the airy purpose of the Civil Rights Act and the reality of the socio-economic disparity faced by millions of African Americans as they sought to exercise these hard-won legal rights in the face of stubborn, ugly racism were obvious, but the short-term intractability of the problem – coupled with the longer-term repercussions of the ultimately doomed Vietnam involvement – were not yet fully apparent. For now, the empowerment bubble was still on the rise, each landmark “First Black X to attain Achievement Y” step being proudly ticked off the checklist, the word “Black” given greater weight than the achievement in question. The tensions which split the nation submerged, winding themselves tighter and tighter before finding explosive release in the race riots later in the decade.

It’s perhaps no surprise that Motown’s “Golden Age” coincides almost exactly with this period. Perhaps more than any other business, never mind any other record label, Motown were quick first to tap into and then successfully mine the mood of the nation between the Kennedy assassination and the riots of 1967, and their speedy reflexes in reflecting and shaping “the Sound of Young America” first took expert advantage of, and then showed the way to, the rapidly-changing radio and TV industries.

But we think of pop music in a series of isolated bubbles, especially if we weren’t there (or then). If the music industry reacted swiftly, far slower to catch up was the movie industry – which makes sense if one considers the magnitude of the sums of money involved to make even a mediocre film. I’m struggling to think of a good example off the top of my head (though I’m sure the comments will be teeming with them!) of a mid-Sixties American film that successfully conveys the spirit of 1964/5, the spirit of change in progress, rather than being an uneasy mish-mash grafting Sixties rebellion onto Fifties staidness.

And so it’s fitting, really, that we get to talk here on Motown Junkies (however briefly) about another American institution – but unlike Motown, so clearly on the rise in the new America, this one was undeniably struggling with the change, its early model now in the subtle but unmistakeable first throes of decline.

American International Pictures, universally known as AIP, had spearheaded the surf and beach party movie genre, one of the first movie genres specifically aimed at teen audiences. These pictures had made a handy profit for the company (budgets were low, expectations lower – it wasn’t unheard of for AIP to come up with a title and poster first, and then write the script to match!), and they cannily packed the movies with pop stars, including opportunities for Motown acts like Stevie Wonder and (yes!) the Supremes. Still, when you look at those early AIP beach party films today, there’s something not quite right about them. It’s not so much that these things embody establishment values (because they don’t, really, and in any case Motown had made plenty of attempts in that direction by trying to appeal to older white audiences), but rather that we’re inhabiting a world that’s not entirely convincing even by its own internal logic, like the details are just ever so slightly off.

Perhaps this particular issue is a racial thing. Conditioned by a decade of famous blues and jazz faces and therefore hip to the fact that many of the hottest artists among the kids’ favourites were black, AIP’s willingness to cast black musicians in their movies is both welcome and understandable – but the actual inoffensive summer-romance storylines were driven almost exclusively by white faces, and the atmosphere of most of these early AIP films feels a bit like some older white guys’ impression of, or calculated attempt at (I don’t know which is better), American youth culture.

It’s not that the details are disastrously or laughably wrong, more that their getting it subtly wrong feels somehow more jarring, like the bits in early Beach Boys records about your best girl and school pride and all that stuff: alien artefacts, created from the mindset of another time. Which brings us back to Dr Goldfoot, theme song for a long-forgotten popcorn flick, and perhaps the goofiest record we’ve yet encountered here on Motown Junkies.

I MEAN RIGHT HERE

I’ll admit straight away that I’ve never seen the film – oh, this review may have taken me two months to write, but my commitment to research hasn’t gone so far as to actually find a copy of it! – but from what I can gather, it looks like an uneasy genre-bending mashup of tropes, made at some expense by AIP and using many of their Beach Party regulars. It’s a confusing project, starring Vincent Price as a mad scientist supervillain who (as far as I can work out) has some sort of plot to take over the world by manufacturing an army of bikini-clad robots. From the reviews, I get the impression this is standard shoddy, camp Sixties throwaway fare, making limited commercial impact (though apparently it did well enough at the Italian box office to spawn a sequel made in that country, Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs, which – perhaps thankfully – won’t trouble us here).

It’s unclear who the movie was aimed at (teens who’d grown up watching AIP’s beach movies? Adult horror fans drawn in by Price, or by AIP’s burgeoning sideline in darker fare via Roger Corman and Edgar Allen Poe?), and from the clips I’ve seen, and the promotional campaign, and indeed this record (of which more in a moment), nobody seems entirely sure whether the film is meant to be a comedy or a spoof, whether it’s mocking the conventions of the spy thriller or using it as a vehicle for silly jokes and girls in skimpy outfits. Either way, it looks desperately unfunny.

The confusion extends to this theme song, too, which seems equally stranded between two islands: is it meant to be funny, or is it a pastiche? Are we meant to laugh at it, or with it, or just dance and not laugh at all?

It would be really helpful to have some historical background here, but I don’t have any. The song seems to have been through at least two iterations other than the Supremes’ version; there are several AIP promos which bob to the surface on eBay sung not by the Supremes but rather Californian garage girl group the Beas – it’s the exact same song, but a different backing track. There’s also a completely different song sung by The Gamblers (“inspired by the film of the same name”, trumpets the label), which in one of those weird Motown coincidences was actually written by none other than Ashford and Simpson, the husband-and-wife writer-producer team soon to pitch up at Motown and create records for the ages. Their Dr Goldfoot isn’t one.

But why are there three of them? And which came first? All I have are guesses. I’m guessing the Gamblers record is an unrelated knock-off of some kind, trying to cash in on whatever business the movie was doing, but I might be wrong. I can also only guess at the Beas/Supremes chronology – did the Beas record their version before or after the Supremes? Did the Supremes record their version before or after they became ultra-famous and mega-successful? These aren’t just boring discographical questions, they’re important for historical purposes. Yes, really.

ORDER YOUR ’66 MODEL TODAY

The thing that’s most surprising about Dr Goldfoot, the song, is how dated it sounds. We’ve covered nearly seven years’ worth of late-Fifties and early-Sixties pop music here on Motown Junkies and this might be the most dated-sounding thing we’ve yet come across – it’s striking just how very inaccurately the writers (Hemric and Styner, previously responsible for Stevie Wonder’s Happy Street, itself an AIP by-product, and Joanne & the Triangles’ sappy After The Showers Come Flowers) have caught the essence of the Supremes, how “off” their ear for what made the group great.

Certainly it throws the efforts of Phil Spector into stark relief; Things Are Changing is no masterpiece, to be sure, but at least it sounds recognisably like the Supremes in unfamiliar territory. This, on the other hand, is only identifiable because of Diana Ross’ voice; at least she seems to be enjoying herself.

With its jaunty, parping rhythms and swingin’ West Coast teen movie instrumentation, this evokes nothing so much as a flimsy, wobbly-set ersatz take on the beginnings of psychedelia, a mid-Sixties narrative for white Americans, now only familiar to me (a Brit born at least thirty years too late to experience the hippie heyday of flower power, never mind the confusing social maelstrom that immediately preceded it) through naff movies. Which is oddly appropriate, I guess. It’s not even grubby enough to be enjoyably trashy, it’s just kind of shabby.

I wonder, though, what people who don’t like Motown – or people who do like Motown, just not the Supremes – hear in this. Or rather, to phrase that more clearly, I wonder if this is what those people hear in Motown. To me, there’s a world of difference between the spiralling majesty of I Hear A Symphony or Baby Love and the clumsy Austin Powers cartoon Sixties shindig going on here. It’s not so much that it’s campy and stupid (obviously it is, and that’s not a crime in itself) or that it’s inconsequential (ditto), or even that it’s the wrong song for the Supremes, which is debatable (though like I say, Diana has some fun with it).

Rather, it’s that the very building blocks of the song have been made without straw. This is a cargo cult pop single, copying the tropes of big girl group hits without at all understanding what goes on underneath, and ending up as flat and unconvincing as a movie set; a Supremes record in name only. It’s often been said (though not by me!) that the Supremes’ glorious mid-Sixties Motown hits could have been given to anyone else and achieved the same success in their hands, but this one really could have been sung by pretty much anyone; that it ended up in the Supremes’ in-tray is a mark not of their suitability, but of their ubiquity, their level of fame.

NO HEART… PLAYS THE PART

Which brings me back to the lack of available information on when this was actually recorded – was it pre- or post- breakthrough? How many Number Ones had they (I’m saying “they”, I don’t know how many actual Supremes are on this besides Diana Ross) racked up before trooping dutifully into the studio to cut this piffle? It’s a fascinating story either way; what’s not in doubt is that by the time the film was released, the Supremes were famous enough to merit AIP pressing up this promo 45 to hock the film. Whether AIP lucked into the group becoming famous after they’d already cut Dr Goldfoot, or whether they got the gig because they were so famous, the fact remains that they were a Big Name, the biggest name on the books of the year’s biggest-selling label.

And still, it’s ephemera, there’s no denying it. With the best will in the world, the interest in this thing doesn’t stem from what’s in the grooves, but from whose name is stamped on the label. Rarity value is a powerful thing when it comes to old vinyl, and for an act like the Supremes, who attract obsessive fans like moons around a giant planet, it’s natural even their outlying offcuts and discographical oddities will find no shortage of takers. When it comes to quirks in the Supremes catalogue, those takers are certainly well served.

And still, it’s ephemera, there’s no denying it. With the best will in the world, the interest in this thing doesn’t stem from what’s in the grooves, but from whose name is stamped on the label. Rarity value is a powerful thing when it comes to old vinyl, and for an act like the Supremes, who attract obsessive fans like moons around a giant planet, it’s natural even their outlying offcuts and discographical oddities will find no shortage of takers. When it comes to quirks in the Supremes catalogue, those takers are certainly well served.

Even in the middle of this amazing mid-Sixties run of Supremes singles – none of them less than excellent pop songs (and yes, I include Nothing But Heartaches in that, before you ask), many of them chart-toppers, several of them outright masterpieces – we’ve already seen their road is strewn with distractions and asterisk-bearing novelties that don’t fit into the “official” discography. Children’s Christmas Song, Things Are Changing, the little-known 45 pressing of The Only Time I’m Happy, the abortive plan to release Mother Dear… none of these would be mentioned in any history of Supremes chart 45s, and yet the non-hits just keep on coming.

Dr Goldfoot is probably the most anomalous of all, because it just doesn’t sound like the Supremes. It’s not off-key, it’s stupid but its stupidity has a readily-understood purpose, it’s even got a chorus hook that might, on a good day, wind up getting stuck in your head. And still it’s a bad record all the same, if not a dreadful one; its main fault, really, is the stall it sets out for itself just by its very existence. For me, the likes of the Beas and the Gamblers’ takes on the concept are nothing but history and dust, filed away with all the other naff obscure Sixties pop-culture debris, exactly where one might expect a jokey tossed-off AIP novelty trinket from a cheap film to reside. But this has ideas above its station; this, it announces, is by THE SUPREMES. It says so right there in big black letters. Which causes problems.

A curious double standard often comes into play when I’m writing these essays, one I’m well aware of. What would be the ideal model for this blog? It’s funny to be asking this question almost 700 essays in, but what’s better: to try and objectively dissect everything in isolation, or to draw in as much context and off-page controversy and biography and politics as possible to inform the criticism? I think the former might be more artistically “pure”, but the latter more interesting and fits more what this blog has become; a Motown track by track guide becomes a history of Motown. So I guess I want to have my cake and eat it, which is why some records by the likes of Smokey Robinson or Marvin Gaye come off worse than if they’d been made by Joe Blow: because we all know they can do better when they give something their all. And that’s what’s at play here.

Even more so, in fact, because the story of the mid-Sixties Supremes is, as we said at the start, in many ways the story of Motown in the mid-Sixties in microcosm. So if we come across a Supremes single in 1965 – no matter however trifling and silly and apocryphal – it’s part of that story, and that is different than your run-of-the-mill cutout-bin AIP beach soundtrack joint. That’s double-edged, too, because it plays into the reason I don’t like it more: for better and for worse, the Supremes are not the Beas.

It sounds like somebody else’s idea of what the Supremes sound like, where that person has either got the wrong end of the stick, or doesn’t even like the Supremes. I don’t want to read too much into it (and I’m not, despite the thousands of words above – you’ll hopefully have noticed this whole review, which took forever to write, is really just a peg to talk about talking about Motown and the Supremes and Sixties America in much broader terms); it’s a silly piece of fluff that isn’t even officially part of the Motown canon at all. But it’s fascinating, because when I play this, I wonder: is this what other people hear when Baby Love comes on?

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in the Supremes? Click for more.)

|

|

| Earl Van Dyke & the Soul Brothers “The Flick (part 1)” |

Chris Clark “Do Right Baby Do Right” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

Thank goodness that’s done.

I won’t leave you all for two months again, I promise.

LikeLike

Big words there, fella.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You know what they say about talking to yourself, lol !!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I finally heard it on the boxed set in September 2000, I had to reconcile myself that astonishingly rich surprises like “It’s All Your Fault,” back on the 1986 25th Anniversary set are not guaranteed every time Motown repackages the same stuff with a teaspoonful of ‘previously unreleased.’ They damn well know, have long known, that fans with 15 copies of “Baby Love” aren’t eager for the 16th, so they let a little more out of the vault, jewels and farts alike.

This is not to suggest in the least that the boxed set isn’t essential. No, I absolutely don’t know how I lived without those extended studio versions of “Stop! In The Name Of Love” and “Everything Is Good About You.”

A rousing welcome back to you, NIxon!! 🙂 We have all missed you and your perfect words.

LikeLike

“Jewels and Farts” would be an excellent subtitle for one of the Lost & Found sets.

144man alluded to this on the last post, but it bears closer examination here – what is the draw meant to be for the 50th Anniversary Singles Collection set? I bought it because it (along with the similarly pointless Temptations one) was marked down, and I’d already bought the equivalent sets for the Tops (worth having for all the UK mixes and B-sides) and Vandellas (absolutely bloody essential, featuring an entire disc of new rarities and the original I Can’t Dance with Martha on it)… but other than the foreign-language cuts (which might have been on Motown Around The World anyway, I don’t know), is there anything on there that’s new? It can’t just be this, because it was already on the 2000 pink box set. Was it just aimed at Supremes fans who wanted all the DRATS singles, but (missed the boat on/balked at shelling out for) the first nine volumes of The Complete Motown Singles?

Anyway, thanks for the kind words, Dave.

LikeLike

Well, it took almost 50 years, but this trifling little fly speck of a record has finally justified its existence by inspiring your wonderful piece. Worth the wait.

LikeLike

Thanks Ken, I appreciate it. I cropped out and rewrote vast sections of this, so there may be undeveloped arguments or threads left hanging, but I can’t write any more about this record for a while.

If someone had asked me at the very beginning what the longest entry I’d write would be, “Dr Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine” would probably have been fairly near the bottom of the list of guesses.

LikeLike

Thanks for the review. I like the song because of its dissimilarity to anything the group was doing at the time. As in Things are Changing, you can actually hear the individual voices and harmonies. I especially love the part where they sing what I guess is the chorus, “Doctor Goooldfoot… And his bikini machine!”. I can clearly hear Flo on that drawn out “Gooold”, her own way of pronouncing the letters o and l. And the harmony on that part…almost drives me crazy, in a fun way, picking out each voice and its part. No, it’s not especially good but it’s fun, it’s definitely of its time, and it reminds me of a great, brief time when we Americans went to the beach on Saturday afternoons, courtesy of our local picture show. I don’t read any social stuff into this. I read only fun. I’d give it a 6 for the sheer novelty of it, and for a rare chance to hear Mary’s and Flo’s voices so upfront and intimate.

Robert

LikeLike

P.S. The Supremes weren’t on the cover of TV Guide; it was TV Magazine which was a knockoff that I think was given away free at checkout counters in stores. They were, however, on the cover of Time during that glorious summer of 65, along with other “rock and roll” acts.

LikeLike

You’d think after two months I’d have caught that, but no. Thanks Robert, duly amended!

LikeLike

That’s fascinating – I might have cloth ears, because I couldn’t make out the other Supremes clearly at all!

LikeLike

That’s such a good essay, Steve, that I grudgingly have to admit it was worth the wait [though you might care to proofread line 3 of paragraph 14].

For those who wish to hear more songs written by Hemric & Styner, Donna Loren’s “The Complete Capitol Recordings” (2014), which includes all the songs from “Beach Blanket Bingo”, is a pretty good compilation that should appeal to girl group collectors.

LikeLike

Amended, thanks!

LikeLike

I couldn’t get this at all until I saw the film on You Tube. To me, this sounded like an attempt to fit the Supremes into the West Coast trend of 1964/65 and came across as really artificial. When I saw the film version, it seemed to me that while the Supremes were singing in front of an audience (white West Coaster teenagers) the group might as well have been in Detroit. The group look bemused while the audience (presumably professional dancers) go through their paces taking no notice of the group. In real life in 1965 teenagers of any race would have been in awe of the Supremes and would have been right up against the stage to be as near as possible to Mary, Diana and Flo. So, visually, it was as artificial as the record sounded. The only good point of the film version, fifty years later, is that it is a record of the Supremes when they were still a group.

LikeLike

Are you referring to Beach Ball? Every time I’ve watched their performance in that film, I’m dazzled by how glamorous and mature and beautiful the Supremes look in contrast to the beach bums and beatniks in the audience.

LikeLike

I was a teenager in 1965, albeit at the very end of the teen years. I wouldn’t have fought so hard to be right at the edge of the stairs to hear them, and wasn’t in awe of them.

The film in which this song appeared was utter garbage. This song is really “sappy”, and not even remotely listenable to me (probably more because it reminds me of the terrible film, but also because the material is so weak. Needless to say, Hemric and Styner are not my favourite song writers, nor one of my favourite songwriting teams at Motown (quite an understatement). Although “happy Street” is listenable. The rest of their songs for Motown are not. This one’s lyrics are utter drivel, and the sound is much too “poppish” for my taste. Diana and The other Supremes (if it is indeed them) do a decent job of singing. But it just isn’t remotely my style. I’d give it a “1”. Better than the “0” I gave to “Randy The Newspaper Boy” and “Happy Ghoul Tide”.

Although, I’m not much of a Supremes’ fan, I can admit that I like “Run, Run, Run, “Lovelight”, “Let Me Go The Right Way”, “Back In My Arms Again” and a few others fairly much. But, I can really do without this one. And, despite my having almost virtually all The Motown released 45s from 1959 -1966, I didn’t ever possess this one (although I had several chances to buy it).

LikeLike

Of course, you may not have flocked to the front of the stage. But I’m describing the activity in the film in which the Supremes were shown on one side of the picture with the dancers (supposed to be teenagers) at the other. All I’m saying is that the set-up wasn’t real.

LikeLike

Yes, I see what you mean. They treated them like they were making elevator music. But, then, just what was realistic about those teen films? I agree that given that they added the most popular singing group to the film, they should have had the kids liking their music, and showing the group some appreciation. Even in the 1950s, the film makers at least had the lily-white kid audiences clapping for (and seemingly liking) the Flamingos and Moonglows and other African-American artists.

LikeLike

Hey Robb – How are ya buddy? Yeah, I saw Dr G – bad, bad movie. Of course you had the stellar acting talents of Frankie Avalon & Dwayne “Dobie Gillis” Hickman so what didja expect. The movie was basically a beach party/James Bond spoof mashup. Of course, you had plenty of pretty girls running around for eye candy. I wonder if the makers of the Austin Powers consciously spoofed parts of this movie (girl robots etc). I just listend to the song on Youbube. They showed the opening credits – early claymation courtesy of Don Clokey of GUMBY fame. I expected the song to actually be much worse. Oh it is definitely not good but with a better arrangement & different lyrics & perhaps someone like the Toys doing it, this could have been a decent Northern Soul tune (maybe!) .

Good old Motown — When they wanted to be trendy they usually hauled out Diana Ross. I mean one moment she’s trilling away on Motown’s Summer of Love offering (“Reflections” – yep HDH managed to sum up SGT PEPPER in one single! Take that Beatles!) next moment she’s singing AND performing FUNNY GIRL! Or she & her gals are singing to the bathing suit crowd in BEACH BALL (dressed like its opening night at the Copa!). Of course, in that very HAIR-y year of 1969 (when every other record was something from HAIR) the Supremes highjacked “Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In” for their stage show & then Motown had the nerve to name their album LET THE SUNSHINE IN. When questioned about that Berry Gordy pled the 5th! (get it?) Of course, Gordy & Hank Cosby whipped up their own little HAIR = piece with the absolutely insane “No Matter What Sign You Are”! (dig those Ows!) If you didn’t listen too closely you might think you were listening to a medley from HAIR! (did you ever notice that Diana shrieks “Hold Me” five times at the fadeout?) Of course, when they needed some homegirls from the hood they dressed Diana & gals in those groovy ghettogirl outfits for “Love Child” & “I’m Livin In Shame” (homeade jam anyone? by the way I’m still puzzling after all these years as to who sent Diana the fateful telegram explaining Mama’s demise. “But honey I thought your mother died on a weekend trip to Spain!”)

Okay I’m done for now!

LikeLike

I look at all of the material that the Supremes recorded from the very beginning through 1966 as courses in their musical education. I look at all of their performances as courses in their general entertainment education. Motown presented them with many, many grand opportunities to advance themselves as entertainers. I am not a Diana Ross apologist, at least not while expressing myself now. But the woman worked her butt off, learning and training and grasping at every chance to grow as an entertainer. Mary went along for the ride and became quite a talented dancer along the way, as well as cultivating an dazzling stage persona. Unfortunately, she allowed her bitterness and resentment cloud whatever chances she had to become a great performer in her own right. Florence… well, I always used to refer to her as my favorite Supreme. But I don’t think she really wanted to be a Supreme after a certain point. She went along with the program as much as she could, but toward the end she looked and sounded tired of the whole thing.

From ’67 on, it was clear that Motown was trying to keep the group afloat and as popular as possible in preparation for Ross’s inevitable exit. And her exit was as effortless and painless as, according to my mother, my birth was.

I could write thousands of words on this subject, but to sum it up, I will say this: The Supremes became something larger than the group itself, and I’d venture something larger than even Motown. I’m sure that Gordy and his cohorts realized this early on, say late ’64, and handled the monster they had created quite well. Other Motown acts, and fans of those acts, complain to this day that Motown lavished most of its attention on The Supremes while neglecting everyone else. Not true. Almost true, but not quite. The thing that the other acts didn’t have was a force of nature like Diana Ross. She was singular in her talent, her appearance, her sound, and her work ethic. She didn’t, as the popular myth goes, sleep her way to the top. She worked her way to the top. She did what she was told to do and learned every step of the way.

I can’t emphasize enough the importance of even insignificant works like the one being reviewed here. Believe me, I’ve had many a job over the past 35 years. But in each job, I learned something about my profession, about working and dealing with people, and I’ve even learned how to do work that’s outside of my chosen profession. Every single day at every single job brought me opportunities to learn and grow. The same thing happened with the artists at Motown. Each person chose to take or not take advantage of those opportunities. “Dr. Goldfoot”, as silly as it is, was such an opportunity for The Supremes. They did it and had one of three movie themes under their collective belt. How many other Motown acts, or pop/rock/soul acts could boast of that in the ’60s?

Robert

LikeLike

Thanks, Robert! This needs to be said! Too many people dismiss the group as being “irrelevant” or “less talented” than the other Motown performers. And it is true that some of the other Motown acts — The Four Tops, The Temptations, Gladys Knight & The Pips, Tammi Terrell and Mary Wells, for instance — were also, in varying degrees, somewhat versatile song stylists.

The Marvelettes, on the other hand, are among those who could negotiate the intricacies of a Motown song, but they failed miserably in attempting to tackle a Cole Porter song. And Martha Reeves, Kim Weston and certain others had rather strident voices and could not rein in the dynamics or adapt their vocals to fit the dictates of styles other than the Motown shouters. When Martha, for instance, took on a ballad like My Baby Loves Me or Love Makes Me Do Foolish Things, she still utilized full-throated, no-holds-barred deliveries. (Those powerful takes were fine, in and of themselves, but after listening to three or four songs in a row, the listener yearned for something else. Aretha Franklin realized this and varied her pitch, tempos and such; Martha or her producers never seemed to understand this, even when the material would have accommodated it.)

It is highly unlikely that any other Motown singers, if given the chance, could have been as committed to the demands of Motown songs yet slipped so easily into the “show business” mode of the mid- to late 1960s and be accepted, no matter the format. Who but Diana Ross & The Supremes could have performed pop/soul so winningly, yet produce credible, convincing Irving Berlin, Cole Porter or Fats Waller medleys on The Ed Sullivan Show or crooned with Bing Crosby, Tennessee Ernie Ford, Red Skelton, Andy Williams, Ethel Waters or Ethel Merman as easily? What other Motown performer could have recorded full albums of Rodgers & Hart, Disney classics, country & western material, Sam Cooke hits and so on as (seemingly) effortlessly as Diana Ross, who had the charisma, the drive, the intuition and the adaptable voice to pull it off?

With the possible exception of Gladys Knight, no one else at Motown at that time could have done it all so comfortably or so well!

LikeLike

Beautifully articulated, Benjamin. There always have been and still are people who disparage the Supremes for whatever reason. Probably because they were so successful and probably because the became so accepted by white audiences and record buyers. Oh well. I think the notion that they weren’t as soulful as they should have been is reverse-racist, as well as beside the point. If they were supposed to be soulful just because of their race… Hmm… I don’t know about that. Anyway, as I said and as you understood, Motown knew what it had in that trio of rough-around-the-edges young girls from the ‘hood. Why else would they have been given so many chances to make it?

I think the apex of their career, the performance that showed everyone (including Motown) what they could do, the culmination of all of those countless “lessons” along the way, was the Irving Berlin medley on the Ed Sullivan show. They had made it to the mountaintop. Many were happy for them and celebrated their achievements. Others chose to be bitter and envious. I’d rather be happy. It just feels better.

Robert

LikeLike

Welcome back, Nixon! I’d almost given up hope of hearing from you again.

But what a return: an exhaustive essay on, of all things, an obscure Supremes’ recording, which, to be honest, I’d never even heard of until you brought it to my attention.

But, of course, your amazing essay was about much more than that. It was an opportunity for you to reflect on the amazing success of Motown and the rationale behind it. It overpoweringly conveyed your love for the music and the legend. Both of which I can identify with—and, unlike you, I was around when it happened. How you capture the passion and devotion that I feel is unbelievably uncanny. I simply cannot understand it.

Regarding this particular recording, though, I don’t feel any deep analysis is required. Berry Gordy was simply looking for any way possible to integrate his artists and sound with white America, and what better opportunity than cinema? Never mind that it was laughable, marginal, silly cinema—it was what white teenagers were viewing. A couple years later he was signing up the Supremes to do themes for (slightly) more sophisticated films like “The Happening.” You can forgive him for thinking a trifle like “Dr. Goldfoot” would help advance his girls much beyond the fame they’d already achieved. It was a moving target, and one hard to pin down.

From our fifty-year vantage point, all of this seems somewhat obvious. But imagine if you were riding this bucking bronco during its heyday. What gold rings would you grasp at? Which decisions would you make? You can fault Gordy for making what, from today’s POV, seem ridiculous choices, but look at the results. Here we are, debating the Supremes’ unparalleled success fifty years later. It only grows more impressive over time. Frankly, I can never stop hearing about it—and, as brought forth in your analysis, always learning more. Thank you!

LikeLike

Well now you be done it. The song has been in my head all day. And I keep singing this crazy song

LikeLike

Great piece Mr Nixon. I put my own incoherent comments here.

Uh… Paging Chris Clark… Miss Clark… are you there?

LikeLike

A very informative and entertaining review, worth waiting for. Certainly Motown became the most influential of all record companies and most successful of all independents, deservedly so. However, I would like to take issue with one of your points about Berry Gordy, Jr. A brilliant composer and music producer without a doubt, but I disagree with your statement about his lack of business knowledge. It’s well known that Gordy,sr ran several successful businesses over the years and two of his sisters ran businesses (Anna Records for instance) before Motown took off. So it’s extremely unlikely Berry didn’t have a good deal of business acumen. Additionally, I’ve always thought the $800 dollar loan to start Motown must have been a bit of a myth. After all, even in 1959 $800 dollars wouldn’t have gone anywhere in setting up a recording company. Let’s face it, the Gordy family could have loaned him many times that amount and probably did. Now down to the film from which this current review item pertains. If “Randy the Newspaper Boy” is a contender for the worst record ever made, then this must be a contender for the worst film ever made. Utterly banal in every respect and even worse than the awful AIP Beach Movies. At least the Beach movies had more musical interludes, albeit lightweight, and the lovely Annette Funicello to ease the boredom, but this film’s got nothing to commend it. Therefore, no matter how bad this recording is it’s got to be the best part of the film. Hemric and Styner seem to be pretty good at churning out ‘cotton candy’ songs for these films, even though I have to admit to liking a few of them. At least the arrangement on this gives it a bit more power than those sung by Annette. Obviously the lyrics are pointless, so we only have the melody arrangement, production and Supremes performance to consider. The melody is pretty shallow but at least the arrangement is full enough to make it listenable. Diana does the best she can with it, but how can you put any conviction to lyrics like that. Basically throw away stuff, but I listen to it occasionally for interest value.

LikeLike

Business *experience*, not knowledge or acumen. Just on the numbers alone, Berry Gordy Jr has to be considered one of the most successful businessmen of all time, which I find extremely satisfying – he picked up what he needed to know from Pops and his sisters, and embarrassed every business studies major in the world by becoming a multi millionaire media mogul despite (by his own admission) not being very good at reading. But he had no experience of success in business before 1959 (his only venture was the jazz record store that went bust), which makes it even more impressive what he achieved.

LikeLike

Berry Gordy learned from his experience in trying to sell Jazz, Blues and R&B in his record shop, exactly where the trends were going in young people’s musical taste. He used that knowledge to first start his musical recording/production services, and then followed up with it in his early Tamla Records venture, and parlayed that into his very successful Motown Record Corporation, and Jobete Music Company, Inc. It’s not that surprising that he made those latter companies successes. It’s just surprising how very successful they became.

I know many people who were failures in a career as an employee, and couldn’t hold a ob, due to incompetence. They all started working as free-lancers, because they couldn’t hold down a job. They all became incredible successes at what they ended up doing. One doesn’t have to have previous small successes to later have a maor success, as long as one learns from his failures.

LikeLike

Hi Robb! Those are really good thoughts my friend. You should teach a class. Hey, what did you think of my ramblings above about Motown & Diana Ross etc? “No Matter What SIgn You Are” by D Ross & Supremes (or Andantes) is playing as I write this. Diana just shrieked out those 5 “hold me’s”! What an insane song! Sort of in the so bad its fascinating category. Can’t wait till we get to 1969. 1969 – the year of Runaway Children, Ungrateful Daughters, Fatal Trips to Spain & lots of Good Vibrations/Good Combinations (or as Diana Ross would say “OW!!” )

Hope you are having a good summer.

LikeLike

Lotta verbiage for such an obscure and worthless disc (but thanks for the verbiage anyway). I’m afraid of what you’ll give us about five singles down the line…

LikeLike

Hey, if you don’t want verbiage, you’re kind of on the wrong blog… 🙂

LikeLike

More verbage here mates! Do you blokes in the UK get the SIXTIES CNN series on TV over there? Tonight they are talking about the British Invasion. I wonder if they are going to do something about Motown & soul music???? Love the Beatles, etc but howzabout Motown?????

Um… paging Chris Clark … please pick up the yellow courtesy phone. Chris… we need you badly!!!!

LikeLike

Patience, grasshopper 🙂 We’re on a weekly or twice-weekly schedule of sorts now, which I hope to keep up for a long time.

Anyway, after a huge post following two months away, it’s no bad thing to give the audience time to read and rebuild (and we’re almost back to pre-hiatus levels now anyway!)

LikeLike

Thank you sir. A totally unrelated question (though DIana Ross related). Was her song “DoobienDoobie” or whatever it was caled ever released as a single in the UK? That is one of the strangest songs Motown ever released. Kind of their “Revolution #9”!

LikeLike

It was a single over here, which means that we’ll cover it on Motown Junkies in a few years time. I played it on my radio show a few weeks ago!

LikeLike

A really interesting piece, Mr Nixon, but surprisingly, it doesn’t really cover the one aspect of this song that i’d love to know the answer to:-

WHY didn’t it appear on The Complete Motown Singles? I just can’t see the logic. Presumably Motown own the rights, for it to appear on both the Pink Box Set and the Complete Supremes Singles thingy – one released before, and one after, it was due to appear on TCMS 1965. Similarly, there was a precedent for TCMS including both Supremes stuff leased out as promos (Things Are Changing, The Only Time I’m Happy), and other artists (The Miracles ‘I Care About Detroit’, Brenda Holloway ‘Play It Cool’), etc. etc.

Do you think there was some specific and complex licensing reason for its omission (not just because it was a bit bad), or do you simply think the compilers forgot it?

LikeLike

Keith Hughes, the co-editor of the TCMS series, is known round these parts, so maybe he can answer that definitively (if he’s at liberty to do so!)

In terms of my own conjecture, I think it’s highly unlikely it was just “forgotten”. Rather, I’d wager it was either a licensing issue, or just the fact that it’s not really a Motown single, and so its inclusion (as with all the other oddities you mentioned) would likely have been somebody’s Motown/Not Motown judgement call. I only covered it here because its inclusion in the Supremes’ Complete Singles box set tipped the scales enough for me personally to include it. There are other non-inclusions (Cornell Blakely, Willie Horton, the Merced Blue Notes, a bunch of Rare Earth sides) and other leftfield inclusions (Lee Alan, the Velvelettes on IPG). As always, my policy is that if TCMS included it then so do I, it gets an automatic pass into the Motown canon; if they left it out, I decide whether or not I cover it anyway. Usually yes, because, well, the more the merrier.

LikeLike

Exellent essay! To answer your question about a film that “successfully conveys the spirit of 1964/65” you should try and score a copy of “Nothing But a Man” starring Ivan (Hogans Heroes) Dixon and Abbey Lincoln. Released in 1964, it also contains and all Motown soundtrack.

LikeLike