Tags

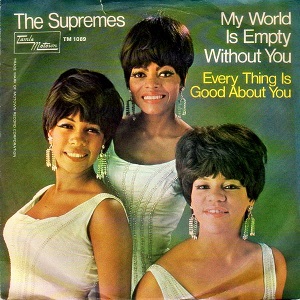

Motown M 1089 (A), December 1965

Motown M 1089 (A), December 1965

b/w Everything Is Good About You

(Written by Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier and Edward Holland Jr.)

Tamla Motown TMG 548 (A), February 1966

Tamla Motown TMG 548 (A), February 1966

b/w Everything Is Good About You

(Released in the UK under license through EMI/Tamla Motown)

And so 1965, for all intents and purposes, is over. Christmas came and went, and Motown had enjoyed their biggest and best year ever, both commercially and artistically; Berry Gordy had started in 1959 with nothing, and after just seven years, he could justifiably say he ran the most successful singles label in America. Bring on 1966, and more masterpieces, and all the further glory and riches they would surely deliver. Right?

And so 1965, for all intents and purposes, is over. Christmas came and went, and Motown had enjoyed their biggest and best year ever, both commercially and artistically; Berry Gordy had started in 1959 with nothing, and after just seven years, he could justifiably say he ran the most successful singles label in America. Bring on 1966, and more masterpieces, and all the further glory and riches they would surely deliver. Right?

But it turns out 1965 wasn’t over, and Motown weren’t done with masterpieces.

The Supremes had hit the heights at the same time as their label, their pop powers peaking at just the right moment and in perfect synchronicity with the never-better Holland-Dozier-Holland writer-producer team. Their last release, I Hear A Symphony, daringly ambitious but successful with it, had returned them to the top of the charts with a new approach, H-D-H replacing the usual lyrical heartache with unexpected sheer heart-bursting joy to accompany the catchy, bouncy, light-filled music track.

The result had been stupendous, a thing of real beauty, but not necessarily a trick that could really be repeated without taking away some of the immortal gloss (from both the new record and the old). So, here, for the follow-up, the HDH/Supremes partnership shows us the other side of the coin: we’ve done happy music/heartbreaking lyrics, we’ve done happy music/happy lyrics, and so now logically that only leaves us only one place to go. Bring on the hurt.

TWO HEARTS IN 4/4 TIME

You might find it ironic, given the subject of the blog and the amount of words I’ve poured into it so far, that I don’t really know much about the singles market in America compared to Britain – so a lot of these observations might be off base. Perhaps you can correct me. But in the UK, the singles market has been through three distinct and radical shifts. The first was the introduction of the 45, which opened up popular music to a whole new generation of record buyers just as they emerged blinking into the post-war light clutching handfuls of pocket money; get ’em hooked young and they’ll never leave you. The last was the digital download, which has obliterated the singles landscape beyond all recognition; nobody buys or even bothers pressing up physical singles any more, beyond a couple of very rare outlying examples, and it’s not at all uncommon to see even huge stadium-filling artists miss the charts altogether with their latest efforts, wall-to-wall MTV exposure or not, if the parent album is already on people’s phones and hard drives. In the middle, in between, came another change: something more subtle, something harder to pin down, a transition that took years to bring its full effect but which changed the market forever.

The lifespan of a pop single – of a pop song – used to mainly happen after it was released and available to buy; once in the shops, the music press would cover it, DJs would pick up on it, the record would start to get played on radio and in clubs, the sales would begin to mount, the single would enter the charts low down and keep rising, perhaps for a month or two (or more!) before hitting its peak in terms of saturation and chart placing.

At some point in the 1980s, this began to change; canny labels realised records sold more on opening day if they weren’t “new”, if they’d been hyped up on the radio and in the press and, yes, by their music videos, perhaps a month or two in advance of the record actually being available to buy, building and building demand without the punters being able to satisfy that new craving; furthermore (in Britain’s 100% sales-based chart at least), if everyone went out and bought it in the first week, the record would shoot into the charts in a high position (maybe even the top), ensuring it would be stocked and prominently displayed ready for week 2. And when we reached the Nineties, by week 3, that single was already old news, because radio and music TV would now be playing the new one.

With that in mind, it’s kind of impossible for me to imagine the sense in a world where Motown put a huge new big-ticket single by their top act out in the week after Christmas, a period which in the UK is now associated with nobody putting out any new releases at all because nobody’s buying new singles in that last week of the year. (Some hard-up acts will always deliberately put records out in the New Year, another traditionally quiet time for singles sales, in the hope that their meagre sales will translate into the exposure and applause of a Top 10 hit, instead of scraping the Top 40 as they might do in May). I have to keep reminding myself that, actually, even though we have another three more Motown singles to cover in 1965, even though this goes down officially as a 1965 release, pretty much nobody would have heard these sides until we were well into 1966 and a head of steam had started to build behind the record. When this crept out, quietly in the post-Christmas winter, people were still digging I Hear A Symphony.

With that in mind, it’s kind of impossible for me to imagine the sense in a world where Motown put a huge new big-ticket single by their top act out in the week after Christmas, a period which in the UK is now associated with nobody putting out any new releases at all because nobody’s buying new singles in that last week of the year. (Some hard-up acts will always deliberately put records out in the New Year, another traditionally quiet time for singles sales, in the hope that their meagre sales will translate into the exposure and applause of a Top 10 hit, instead of scraping the Top 40 as they might do in May). I have to keep reminding myself that, actually, even though we have another three more Motown singles to cover in 1965, even though this goes down officially as a 1965 release, pretty much nobody would have heard these sides until we were well into 1966 and a head of steam had started to build behind the record. When this crept out, quietly in the post-Christmas winter, people were still digging I Hear A Symphony.

Probably right too, because festive this is not; despite the driving uptempo backing, there’s a sadness in these chords and changes and sweeps that feels somehow kind of desolate and inconsolable, even without the lyrics. With them, it’s as much a howl of anguish as three impeccably-coiffed ladies in impossibly sparkly ballgowns can possibly muster, and it’s quite the thrill-ride. Also, it’s magnificent.

ALONE WITH THESE FOUR WALLS

I say three ladies, but really this is as much a Diana Ross solo performance as any of the Supremes’ singles have been so far; Flo and Mary don’t really get given very much to do at all, and Diana’s co-stars are instead the Funk Brothers and the string section.

I say three ladies, but really this is as much a Diana Ross solo performance as any of the Supremes’ singles have been so far; Flo and Mary don’t really get given very much to do at all, and Diana’s co-stars are instead the Funk Brothers and the string section.

This is a Sad Song alright. It’s a kitchen-sink drama; where usually HDH would combine the beautiful bounce and swagger in the music with the anguish of the lyrics to heighten the effect, here the pain in the blood of the music not only reflects but amps up the domestic tragedy of the words.

Or is that the other way around? In lesser hands you’d have a sticky melodrama, and for sure there are clunky moments aplenty here, mainly to do with the way the lyrics and music interact, a strict AABB structure which gives us Diana Ross delivering a litany of rhyming couplets. It all feels a bit strange given the innovative meter and rhyming schemes the Supremes/HDH collaborations have brought us before, and it doesn’t make for a smooth ride. And some of the couplets either don’t scan –

“Inside this cold and empty house I dwell / In darkness with memories I know so well”

– or just sound forced and artificial:

“My mind and soul have felt like this / Since love between us no more exists”

…Who talks like that? For a group where you’re so often taken on a magic carpet ride through seamless pop perfection, the Supremes sure had a habit of dragging you back bumping along the earth from time to time. This is like the artful roughness that pockmarked Who Could Ever Doubt My Love, only ratcheted up yet further.

But not for nothing did Berry Gordy circulate that famous memo stating Motown would “only release Top Ten product” (and the Supremes only Number One material, to boot); the craftsmanship on show here is something wonderful to behold, skilfully woven into an undulating, choppy sea of woe, and it’s all about the music.

This is maybe the best band track we’ve yet encountered on Motown Junkies, full of grit and tears and strange, alien sounds all charging forward as one. From the very beginning, the buzzing distortion from a thudding bass drum almost a beat in itself as it charges the air with what’s about to come, we know we’re in for something new. The horns, the drums, the bass, everything is as good as it has ever been; 1965 is over but Hitsville is at its peak.

I’ve talked before about how Motown used strings as more than a garnish; where other, lesser labels might throw in a string quartet to add instant gravitas and grown-up credibility to their teenybopper jaunts, Motown (and HDH and Smokey in particular, schooled in the theory of classical music as well as blues and jazz) innately understood how, properly used, the strings could build the song – indeed, how the strings could be the song. In the case of My World Is Empty Without You, the defining solo isn’t a sax, guitar or organ part, but rather a wordless stretch of violins at 1:15, so high as to almost be climbing like vines out of the listener’s audible range, twisting and grasping and tangling as the melody pulls them taut, Diana’s pain bouncing off like helpless echoes. Even more so than on I Hear A Symphony with its endless modulations rising up to heaven, here the strings tell the whole story that Diana can’t quite put across.

It’s a record full of pain, this. Even after dozens of plays, while the HDH/Diana/strings combination lets us know exactly how the narrator is feeling (the picture is unflinchingly stark, right down to the nails-on-a-blackboard pizzicato stabs of unease at unconsciously remembering some little detail that haunt her every waking hour following a horrible breakup), I’m still not entirely sure what she wants the listener to do about it. The obvious reaction is that she wants him – us – to take her back, but actually on further reflection there’s very little of that in the song either, no particular reason for this relationship to start up again beyond the fact that the breakup has blind-sided her. She needs his “strength” and his “tender touch”, and love, but she always stops short of saying she needs him.

I need love now, more than before

I can hardly / Carry on any more

Hold on, what’s she threatening to do here? We’ve mentioned the S-word before in relation to the Supremes, and we’ll come to it again soon enough, but this really does sound like a woman at the very end of her tether, as though she truly, genuinely believes her world is empty without him. (In fact, just think about that title for a moment – it’s not just catchy and memorable, it’s actually bleak as hell.) And there’s no chink of light in the darkness to lighten things up, as in the Temptations’ similarly dark Since I Lost My Baby or the Miracles’ exquisitely tortured Ooo Baby Baby; this is a cry for help, to the point it almost feels voyeuristic to intrude on someone’s darkest hour like this.

But then, she’s inviting us in – she wants us to listen. It’s addressed in the second person throughout, casting the listener in the role of the ex, the Emptier of Worlds. Perhaps as a result of this casting, it’s deliberately vague on specifics; we don’t know much about the relationship or what went wrong, only that something did go wrong – and, unusually, it’s even left up in the air as to whose fault it’s meant to have been. All we have is a primal wail of shock that this breakup has happened, and a series of gut-punch vignettes to sum up what it’s done to her. (And it opens up a further theory: maybe it wasn’t a breakup at all – maybe he’s gone in a more permanent sense, whether to Vietnam or to Heaven.) Weighty stuff alright, almost impossible to reconcile with the fact the last time we met these ladies they were singing Dr Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine.

But then, she’s inviting us in – she wants us to listen. It’s addressed in the second person throughout, casting the listener in the role of the ex, the Emptier of Worlds. Perhaps as a result of this casting, it’s deliberately vague on specifics; we don’t know much about the relationship or what went wrong, only that something did go wrong – and, unusually, it’s even left up in the air as to whose fault it’s meant to have been. All we have is a primal wail of shock that this breakup has happened, and a series of gut-punch vignettes to sum up what it’s done to her. (And it opens up a further theory: maybe it wasn’t a breakup at all – maybe he’s gone in a more permanent sense, whether to Vietnam or to Heaven.) Weighty stuff alright, almost impossible to reconcile with the fact the last time we met these ladies they were singing Dr Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine.

And yet, here’s where the genius of Motown comes in, of HDH, of the Supremes. It never feels melodramatic, even though on paper it obviously very much is – it feels completely genuine, and the pain somehow conveys an urgency, a need, from her heart to your hips and your feet. Nine times out of ten, any hacky Tin Pan Alley writer who’d dashed off those clunky couplets would have set them to a ballad, a slow and stentorian OTT piano number beating you over the head with its Emotional Importance; nine times out of ten, if someone had written those lyrics nowadays and given them to an R&B starlet, we’d have a melismatic soup of I AM IN PAIN LISTEN TO ME. But this is Motown, and this is Holland-Dozier-Holland, and so instead what we get is a pounding dancefloor blast, the beat of the drums and the beat of Diana’s heart intertwined, all underpinned by those soaring, twisting, hurting strings, a mockery of grandeur for a mockery of love.

So, just maybe, this isn’t meant as a desperate take-me-back plea, or a tear-blurred goodbye cruel world, or a graveside lament over an unopened Purple Heart box. Maybe Diana is going out and trying to prove herself wrong, or at least do a passable enough impression of it to fool her ex. Maybe it’s meant to be “my world is empty without you – so I’m filling the space with someone new, or with friends or dancing or wine or WHATEVER but not you, pal, you’re history”. Or maybe the dance beat signifies the intensity of her feeling, a woman who’s always been more at home on the dancefloor than crying into her pillow now heading (metaphorically if not physically) back to where she feels strongest. Or maybe it’s just the old happy/sad thing again, the vim and vigour of that Motown beat playing against not only the tragic lyrics but also the salt in the tears of the music. Whatever’s going on here, it’s spellbinding.

It’s always a thrill to hear what Holland-Dozier-Holland and Diana Ross and the Funk Brothers, in any order you like, could do when they all put their minds to something, the magic they created. Here, the music is designed and deployed to devastating effect, the vocal is as good as anything we’ve heard from Diana so far, the whole package is quite startling. It creates a lump in the throat almost exactly as big as I Hear A Symphony, but for entirely different reasons: this is the saddest-sounding outrageous pop stomper I’ve ever heard, and it’s a masterpiece.

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in The Supremes? Click for more.)

|

|

| Jr. Walker & the All Stars “Baby You Know You Ain’t Right” |

The Supremes “Everything Is Good About You” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

yesssss … the very best of the supremes … thus far!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Agree! This is my third favorite from them. The other 2 have not been mentioned yet.

LikeLiked by 3 people

So here’s our first Valerie Simpson-esque bridge (@1:26) and it’s by HDH!

Definitely a 10/10 – can’t wait to get to the two mystery songs that Damecia says round out her Top 3.

LikeLike

As Diana sung in 1971 “…and I’m still waiting”…lol…I’ll be glad when my other 2 songs that fill my top 2 are up for review.

LikeLike

I can never remember which of these you approve of and which ones you would chew me out for liking, so I’m glad this time we agree!

LikeLike

I agree, my absolute favourite single by the Supremes, and that is saying a lot.

From the opening, Diana Ross’ vocal (one of her best, among many). To this day I still play it in the car and am amazed how it has held up over the years. I have no idea why this did not fly up to Number 1, it deserved to be for sure.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I don’t know about the UK, but it was Nancy’s Boots and Staff Sgt Sadler’s Green Beret here in the US.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t argue with a ’10’ — that intro grabs me every time, even after nearly 50 years. Pure magic. But the song itself is a little too one-note for me, which brings it down a notch in my score. There are many other Supremes discs that, I feel, surpass this (such as…hmmm…the next one, perhaps?), but that’s being somewhat unfair, as we’re talking an embarrassment of riches here.

Your description of the British singles market in the mid-1960s was interesting. I always knew it was a bit different from the U.S., where radio stations typically did not start playing a single until it was available in the stores. I also think the popularity charts, such as Billboard and Cash Box, were formulated different than the British charts, weighting sales and airplay differently. The result was records, even those from hot artists, entering the chart at a lower ranking and then gradually climbing. Very few would debut in the Top Ten or anywhere near. “My World is Empty Without You,” for example, entered the Billboard Hot 100 at #75! (And this was a follow-up to a Number One.) It would take six weeks to reach its peak of #5, a criminally low showing for a superb record. But such was the intense competition in those days.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Nick!

Something a lot of US readers don’t realise – the UK singles and albums charts were and are 100% sales-based, with no airplay/popularity component at all (and hence no possibility for “accidental” double A-sides unless the record label designated them so).

LikeLiked by 1 person

The UK singles chart ‘used’ to be entirely sales based, but some three or so weeks ago (maybe more), the OCC – the Official Charts Company to you and me – decided to integrate streaming figures. Whilst this is, to my mind, a silly decision, it is even more ludicrous when you consider that these streaming figures are also being used to certify silver, gold and platinum discs! I know somewhere you can find the figures that the OCC are using (so many streams equate to a single sale, for both chart and certification purposes), but suffice to say, the singles chart is now no longer sales based. I don’t think it will end there either – You Tube views perhaps?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, how bizarre! Thanks. The more you know, etc.

That would be infuriating news, if the singles chart meant anything any more 😦 I used to memorise Number Ones and chart positions, now I couldn’t name you most of the biggest selling singles of the last ten years.

LikeLike

Then my forthcoming series of books based on the UK charts split into decades will prove invaluable!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sold! I love chart books.

LikeLike

That intro was so doom-laden it made me think of the end of the world, and it also used to do strange things to my stylus. I can’t argue with a “10” either, and was surprised when the record stalled short of Number One.

LikeLiked by 2 people

All things eventually come to an end, and in this case sadly, it is 1965. As a drummer what is there not to like about MWIEWY.

I do recall watching TV and seeing The Supremes riding in the back of a convertible looking, well, Supreme. Smiling and waving to the crowd, lip-synching to this during the showing of the Orange Bowl Parade in Florida. Smokey Robinson and the Miracles did a dreary, depressing version that thinking about it now saddens me. Whenever I hear this, I think of the Stones ‘Paint It Black’, and the other way around. If in my mind, IHAS the previous Supreme single is a 10. I would put it at 7, maybe 8 on a good day.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Return to Love or should I say Return to Being a Motown Junkie! Lol. Hi everyone, I’ve missed you all. I saw the preview for this article in my inbox with a big FAT 10 (yes! I can never tell how Nixon will rate these classics and I know he only has 50 10’s to give out, so I was elated to see My World Is Empty Without You being awarded one of the 10’s).

In my opinion, there is no Supremes song that sounds like this, yet this song sounds so much like the Supremes and HDH if that makes sense. If not, let me gladly elaborate. From the opening organ lead, the baritone sax, the claps in the background and all the chord progressions and even the structure of the song with the repetition from the harmonies making the song catchy as ever, anyone can tell that this is an HDH creation. From the “ooo’s” and the “I need you babe”s” from Flo and Mary in the background to the way Diana coo’s “without you babe” on first listen you could tell that this was yet another treasure from the girl’s, as Ed Sullivan would say = ). And let me not forget to give praise to the amazing Funk Brothers who really played the s*** out of this song!

I must mention that I think the length of this song is just right, there is no unnecessary one minute of filler found in the song. It serves it’s purpose and makes you want to repeat it. Miss Ross’ delivery is impeccable. Her singing becomes more painful and stronger the more she sings.

In typical HDH fashion the lyrics of the song are as about sad you can get, Diana sings brilliantly “From this old world, I try to hide my face, from this loneliness

there’s no hiding place,” You’re thinking this woman can’t get anymore depressing, lonely and maybe perhaps desperate for love from the one she says is making her world empty until she belts with everything that she has,”I need love now,more then before, I can hardly,carry on anymore.” Mary and Flo add the longing,dreariness and sorrow to the song, you can really feel with there almost haunting and Gothic background vocals. With that being said about the dark undertones, this is still a song one can nod their head to, perhaps even pat the foot and smile at the sheer brilliance of this record.

As good as it was nearly 50 years ago, this song still holds up well and sounds contemporary. “My World Is Empty Without You” has an edge that no Supremes song had since or before its recording. Even though it was ‘sweetened’ with the strings, it still remained ‘gritty’. It was the perfect mix of three pretty and talented girls who were now international stars, but still from the Brewster projects of Detroit.

I have to mention as always, great job Steve D.! I love the single history lesson you gave in the beginning.Your witty as usual which is a treat. If you’ve read my dissent, I had to disagree with you about Flo and Mary. I think they made the song just as much as the instrumentation and Miss Ross. Your love for music really shines through in your writing. Great job!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Oh yeah I forgot to mention, I wish Ross would sing the song this way instead of high jacking the tempo during concerts. It’s such a good song to display her vocals.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Here’s a theory as to why this wonderful, (deservedly) 10-rated song stalled in the U.S. at #5 on Billboard: at this time, late 1965, the Supremes were strongly identified as a cohesive group consisting of three distinct personalities. Everyone knew who Diana, Mary and Flo were and they were perceived as “equals.” Along comes a release which hardly features 2/3 of the group. I think a lot of listeners were put off; I know I was. It just didn’t sound quite right to have Mary and Flo so far back in the mix. Take a listen to the 2012 remix on the expanded edition of the album “I Hear A Symphony.” If this version had been the single I think it would have soared to the top of the charts. What do you think?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great as the record is, the single mix is ‘way too trebly and echo-y…it might have sounded nice on the 3-inch speaker of a pocket transistor radio (which is how most people heard it anyway), but sounds like hell when shot through a proper hi-fi system.

LikeLike

Bollocks it does. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

without a doubt this is one of their best singles and ROSS vocals. it wasn’t as pop oriented as a few previous singles but just a great non the less.

I recommend listening to the Motown remixed version of which this song is turned into a slow jam and ross vocals shine thru out it gave me a new appreciation of the song and of Diana. she actually feels the lyrics of the song and you feel she has been wronged. this song is in my top 5 Supremes song and I have to agree that the NEW version on the IHAS deluxe is beautiful. it is actually my favorite version of the song

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree with your assessment, Mr. Nixon, and I love the comments I’ve read. Brilliant record, brilliant review, brilliant comments… bouquets all around!

I, too, always found this record similar to “Paint It, Black” by the Stones. Since the latter came out around a year later, I think the Stones were influenced by the former. Wouldn’t be the last time a huge hit record sounded like a Supremes song; listen to “Head to Toe” by Lisa Lisa and Cult Jam. Sound like “Back in My Arms Again”.

This record is what I sometimes refer to as the Supremes’ two funereal songs, the other being “Love Is Here and Now You’re Gone”. Also, those two are my favorite Supremes song titles, both being complex sentences. I’ve always love the eerie feeling of this song. I can imagine a girl, Diana Ross?, sitting alone in a dark house, missing her ex. The song takes the listener on a ride that leads to the edge of sanity, an edge that unfortunately many jilted lovers cross. I remember years ago, actor and game show host Drew Carey derided this song, saying something like “Your world is empty without someone? Get a life!” Well, some people find it hard to do that after a breakup. I think this song brilliantly portrays the obsessive lengths that people will go to in their own heads after a tragic loss. It reminds me of the equally brilliant and disturbing “You Oughta Know” by Alanis Morissette. It also reminds me of the final scene with Liza Minnelli in The Sterile Cuckoo.

Although I love the 2012 remix, I much prefer the original release. The background vocals are spooky and add to the air of mystery and tragedy. With the backgrounds pulled forward, it becomes a little less scary, and I want this song to scare me. Which leads me to the group’s performances of it on TV and in concert… It’s always a treat to see DRATS do their thing, but they really did overdo it with the smiles and dance moves on this song. That’s why my favorite way of enjoying this song is listening to it in its original funereal glory with my eyes closed.

This is my all-time favorite Supremes non #1. I listen to it in my head many times. I’ve even thought about how other song lyrics, such as “On the Road Again” by Willie Nelson would sound with the MWIEWY backing track. Fits in just fine.

I think that’s all for now!

Robert

LikeLiked by 3 people

Totally agree. And for me, the rather large bonus: the flip side is my favorite Supremes song, ever.

LikeLiked by 3 people

This is one of my favourite Supremes’ songs, and favourite of their later recordings. I’d give it a 9.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This was a fantastic record, and I’ve always liked it, but it never made me sad despite telling a very sad story. It’s the way Diana puts it over. If it makes me visualize anything it would Diana surfing! It feels like it goes at a breakneck speed and Ross is out to show us how well she’s managed an obstacle course. The performance is so masterful and assured, the lyrics become something like exercise equipment that she thoroughly dominates. But yes, put it on for me anytime, for its vindication of a woman once inflicted with “He’s Seventeen,” “My Heart Can’t Take It No More,” and “Rock and Roll Banjo Band.”

I love it, but real Supremes Heaven, the record I was waiting for, came when I turned the 45 over. So any way any of us slices it, Motown 1089, yes, is a real 10.

First issues of the single, by the way, and I have one or two, do not carry the plug the Symphony album, which didn’t really exist to buy till mid-February ’66. I still remember that frozen weather sojourn to downtown Philadelphia to fetch the album.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I remember the DJ on the oldies station from when I was growing up in the early 90’s (WKLX in Rochester, NY), when talking over the intro, saying how he always imagined Diana Ross riding up on a white horse while singing this song. That image has stayed with me whenever I hear this song, even twenty years later. Strange image I guess, but not as strange as the girls smiling and dancing to this emotionally intense drama of this tune. Not my absolute favorite Supremes record, but a solid 9 for me, maybe even a 10 on those days when I need a to hear a sad song or two.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve always liked this song. The recording has a frenetic energy, everything seems to be on edge and running at breakneck speed- Diana ‘struggles’ to keep up and fit the lyrics in- everything seems to be running away from her- it’s all out of control- filled with tension. The main reason it didn’t hit No1 is probably very simple- Supreme saturation-public exhaustion- Supremes overkill in the States with so many releases during 1965. Similar to Abba in the UK in 1976 when Money Money Money failed to reach No 1 after 3 previous No1s that year.

I’m amazed that you fail to mention that this record was a complete flop in the UK- Back In My Arms Again did poorly, Nothing But Heartaches failed completely and I Hear A Symphony scraped in at the bottom of the chart. From June 65- June 66 was a bad run for the girls in the UK- Why? The Supremes were by that point an established act. I assume these records were played heavily on the Pirate Radio stations so why did they fail? This has always puzzled me. It is also interesting that despite their mega success in the States they failed to reach the UK top 10 with so many of their releases. The Four Tops were by far the most consistent Motown act on the UK charts.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This too for me is a Motown masterpiece! On one of the Supremes earlier Ultimate Collection CDs, the single mix is superb! The violins in the instrumental break are more audible and happens to be for me, one of the highlights of this great piece of Motown magic! I agree with a 10 as this is probably one of my Top 3 favorites by the Supremes! And yes, the B side is one of their best as well. “My World” is also best listened to in the single mix..the stereo version is way too flat!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I swear I checked your blog just a few a days ago and you were still on hiatus …. But here you’re back (welcome back) and with a million comments to boot. This is indeed a 10! The intro is so eerily powerful that I could identify the song even behind the chatter of the DJ Is that an organ playing the same notes as the bass? As I’ve gotten older, my go to Supremes songs have changed Where Did Our Love Go, Symphany, this one, the flip, and maybe Reflections, and a few album cuts have stood the test of time. These songs are not download today, forgotten tomorrow . Even though I don’t remember this song new, I encountered it during the Supremes era. and I’m happy for it. This song really is a Diana Ross single and she does a great job on it. The album cut brings out the back-up a lot more but I can’t say it’s any better for it. I think you’re going to give Everything a 10 too. I also have a feeling you’re going to buzz kill You Can’t Hurry Love ( because of Phil’s version) I haven’t read all the comments yet, so back to them. Glad you’re back, great review!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m glad to be back!

This time, I wasn’t on hiatus, WordPress just decided (in their infinite wisdom) to roll out another one of their insane unannounced changes overnight. This one introduced a brand-new editor which somehow rendered the entire site nigh-on impossible to update or edit, meeting with a 140-page thread of screams from users on their support forums.

The changes were universally panned – googling the phrase “Beep beep boop” gives you some idea of how much fun this was, but the best example is that it somehow made me side for the first time ever with (climate change denier) Anthony Watts, who I normally disagree with vehemently on almost every conceivable issue, but who posted a rant where every single word was the complete gospel truth.

(For me, I couldn’t get past the crash screen in Watts’ point 7, so I never got as far as being able to use the old posting screen because the new one would just freeze up.)

It was especially infuriating as I’d just gotten back into a rhythm of posting again, with the plan of typing and cueing up loads of my handwritten notes and bits of ideas into new entries while the kids were away for a few days. Instead, I had three weeks of fighting the interface, and then haven’t been able to get back in front of a computer for any serious time since August. But I’m back now, hey ho. Thanks for waiting, everybody!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nixon –

Glad to see you back (and bristling). But appalled that Anthony Watts’ idiot fame spread beyond the U.S.

But more pertinently this is a great Supremes record and a superb worthy entry. Not quite a 10 for me but a definitely a solid 9.

Welcome back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t get me wrong, I’m certainly no fan (and he still managed to screw up the list of problems by putting the fact YOU COULDN’T ACTUALLY USE IT FOR BLOGGING only seventh, below such vital issues as “it makes WordPress seem juvenilized” and “it is visually annoying”)… but even a stopped clock is right twice a day, and – perhaps for the first time ever – everything he said in that post is exactly right.

Furthermore, I wonder if the very public hissy fit from one of WordPress’ most visited (and therefore most ad-profitable) hosted blogs may very well have played a role in them backtracking and reinstating a system that ACTUALLY WORKS ON MY COMPUTER, meaning that future Motown Junkies posts existing at all might, conceivably, actually be indirectly thanks to Anthony Watts. I know, I know. But it’s true.

LikeLike

I was up at three in the morning typing the above comment, so forgive my disjointed thoughts. Did you know there was an alternative version of “My World.” This was originally recorded as a tribute to Berry Gordy ( maybe at a Christmas party? ) and the Supremes sang ” We couldn’t get along without you, We couldn’t get along without you.” I first heard it on the 25th Anniversary album in 1986. A two for oner.

Regarding singles and their evolution, I used to love tracking songs I liked on the Billboard or local radio station charts . I felt involved in the whole system. I liked studying the record sleaves. You can’t do that now.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Your review of this record is superb! It’s a thought-provoking analysis, filled with specific details and observations too often left unsaid by pop/rock critics, especially those from Rolling Stone, who tend to be very dismissive of Motown in general and Diana Ross & The Supremes in particular. After four readings over several days, I’m still not sure I’ve felt the full impact of each of your remarks, but I appreciate every word!

With regard to releasing records in late December, it may have been a teen-friendly strategy, and it worked! Back in the day, at least in the Chicago area, my favorite station abandoned its usual format for the final week or two before the holidays, playing back-to-back Christmas records, rather than the Top 40 hits, and while the Yule fare was pleasant for a time, it did get tiresome, especially by December 25th.

I have specific recollections of sitting in a darkened room, illuminated only by the lights on the Christmas tree, in 1964, thinking that Come See About Me sounded even better in that shadowy, tinsel-and-glitter-sparkled environment; Diana Ross & The Supremes seemed to sound even more glamorous, sexy and so on, and it was a good alternative to the radio. Probably I listened to I Hear A Symphony in the same general setting in December 1965.

But to the point: it was always a relief on December 26th, when the radio station reverted back to its Top 40 format, and it was a special treat when there was a new record, such as My World Is Empty Without You, included in the mix. As a teenager, I was filled with anticipation before Christmas, and afterward, when the gifts were opened and the extended family dinner was consumed, there was a let-down feel, especially with a week more of vacation to get through before school resumed in early January. So my friends and I would meet at the local record shop, intent on buying new releases (if any) and then head to the soda shop, one of the few teen-friendly places in our small town. I expect that many teens, with Christmas gift money to spend, were in similar straits of boredom following December 25th, so it made sense for Motown to release new product then. Kids had nothing to do but buy, buy, buy.

Like others commenting in this forum, I agree that the prominence of the soaring violins on the mono (single) version of My World Is Empty Without You really propels the mood and intensity of the recording. Unlike some others, though, I believe that it would have been a mistake to bump up the backing vocals. Just as in Where Did Our Love Go, where their voices were not heard until the third verse, it was/is necessary for a solo voice to establish the theme of the piece before other voices join in to reiterate, embellish or otherwise expand the prevailing attitude. And having listened again to the 2012 remix just now, I must say that someone, maybe Florence, sounded distinctly off-key when her vocal was bleating away during the initial moments of the song. It was unsettling, jarring and off-putting, and I suspect it would have caused the single to climb even less high on the charts.

Similarly, the stereo version of Stranger In Paradise was ruined by the early introduction of Mary and Florence’s wailing. The illusion of an isolated singer caught in the splendors so carefully crafted in the elaborate string-drenched opening was negated immediately. Instead of a soloist expressing her feelings, you had three women, each having exactly the same feeling of wonder/rapture and exactly the same emotional experience simultaneously, and the narrative no longer felt honest. The background voices no longer supported the lead vocal’s conversation with her lover; instead, it was like three young women each assaulting the hapless man at the same moment, each demanding attention. The (songwriter’s/singer’s) intended intimate confession was suddenly a different scenario entirely.

Thus, the diminished presence of Mary and Florence here sounds natural. Their voices, echoing softly in the background like an almost subconscious, repetitive subtext, enhance the storyline and don’t take away from the lyrics.

As constructed and as originally released, this is one of many perfect iterations, and it remains a favorite single after all these years.

Along with other commentators, I noticed the similarity between this song and The Rolling Stones Paint It Black, and I used to think that an enterprising band, say Vanilla Fudge or Rare Earth, could slow down the insistent tempo of the H-D-H production, toss in a few sitars and a vaguely Middle Eastern mantra background and segue, effectively from My World Is Empty Without You to Paint It Black in a late-1960s-type, seemingly drug-induced, hazy production.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Agree this is a great song & production, but for some reason I don’t find myself rushing to listen to it. Still a fine song. I wonder if this was the template for H-D-H’s work with the 4 Tops (“7 Rooms of Gloom”, “Standing in the Shadows of Love”). While Diana Ross does a fine version, I wonder what the 4 Tops would have done with this song. FYI – I just listened to a version by Jose Feliciano which is pretty good. Cheers to all on this rainy Columbus Day in States!

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s an excellent record – and (as usual) you’ve presented a thoughtful, penetrating

analysis. But – go ahead and shoot me – I’ve always preferred Barbara McNair’s slowed-down, timpani laden version. Also, of course, on Motown. But, as far as chart ranking’s concerned, a complete non-starter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will have to listen to Barbara McNair’s version. You should check out Jose Feliciano’s version. He slows it down a bit too. Quite a good version!

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’ll be coming to Barbara McNair’s version here on Motown Junkies in due course, as it was released on 45 later in the Sixties, so keep your powder dry for now, folks 🙂

LikeLike

For H-D-H, this would appear to be a dry run for some of their later compositions for the Four Tops, most namely “7-Rooms Of Gloom,” if you’ve heard the lyrics to that. But still, #5, though a comedown from the six #1’s The Supremes had had to this point in the States, was an improvement over the #11 showing for “Nothing But Heartaches.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are right on with that (a dry run for “7 Rooms of Gloom” for 4 Tops, etc) See my comments above. I wonder if this song’s #5 status had to do with it being a bit different sounding than their previous hits. Maybe it was a bit of a shock for listeners to hear such downer lyrics, especially after the very uplifting “Symphony”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An interesting 2002 cover by jazz singer Kevin Mahogany. Sparse, slowed down…

LikeLike

This marvelous recording put HDH in entirely new form of maturity as composers/producers. This is so far advanced, both in musical structure and lyrical content to the likes of “Where did our love go”,”Baby Love”, etc it’s difficult to believe it is by the same creators. Not that I’m condemning WDOLG or BL, it’s just that they were essentially music for teenagers, whereas MWIEWY is music for adults. That’s probably why this masterpiece didn’t reach #1 and the others did. Not only is the song a great advancement, the production/arrangement is as well. Complex and quite disturbingly dark in places reflecting the anguish in lyrics wonderfully. 10/10 without a doubt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

just a after thought, not an expert but I am a fan and love Motown.i would also give this song a 10, but could it be how many times this song was performed on television???..compared to the other songs…..to my memory, it was only performed once.?? do you think that if the song was performed more it may gone to #1. I thought the same about LOVE IS AN ITCHING IN MY HEART.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Twice that I know of. Once on Sullivan and once on Sammy Davis’ show. Part of it was done in hits medleys, I think on Sullivan and TCB.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Chartwise it didnt do what it was suppose to do because at that time we slowly…slowly started embracing gutsier music (Otis Redding was on fire in ’65) and the Supremes were in overkill mode. If its playing all day on the radio and on the Sullivan show on Sunday, why spend the money single when you steal a copy from one of your friends? Works for me! Either way its a great song to sing along to but very difficult to dance to. 9 1/2.

LikeLiked by 1 person

like the tune its a great sing along. but I found the honking saxophone (?) a bit tedious and repetitive. there are some nice remixes of this tune on youtube that minimize that honking in favor of more musical elements. IMO not as fabulous as Love Is Like An Itching In My Heart and its awesome flip, He’s All I Got

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great track. I’m amazed that this was a complete flop in the UK failing to chart. This was their fallow period in the UK charts- for some reason the Supremes failed to click with the record buying public at this point. Stop! In the Name of Love was their last top 10 hit- Back In My Arms Again scrapped the bottom of top 40, Nothing But heartaches failed, Symphony just scrapped the bottom of the charts now yet another flop and yet further failure with Love Is Like an Itchin’ In My Heart. Listening to songs that did chart during the period that this string of Supremes tracks failed has me scratching my head as the the girls were releasing quality recordings. Why did they fail so spectacularly, The pirate’s played them? It’s also worth noting that the Four Tops were by far the most successful Motown act in the UK regarding consistent run of chart hits and top 10 placings. A fact often ignored.

LikeLike

the remix of this is great from Motown Remixed. take a listen to dianas vocal. wow amazing. 10

LikeLike

“The MELODY MAKER is always saying that Diana Ross should go solo, and hearing this recording one imagines that it is already a fait accompli since Flo and Mary can only be heard in infinitesamal amounts. Apart from this criticism though the song is an infectious one and opens with an adorable riff that is in deepest funk. It has swing and drive and could be a hit over here. 4/5

“Flip is almost, but not quite as good, but again one is left wondering where did our Flo and Mary go. 3/5”

[Dave Godin, Rhythm & Soul USA 1, 1966]

LikeLike

This is my second favourite Supremes song after Stop! but i think it is possibly their best song overall because it is so very different to anything else they ever did. I often wonder if that is the reason it only reached Number 5 in the charts, because it is so different to their other songs. Which position a song reaches in the charts, and whether it reaches Number 1 or not, does not always match up with how great the song actually is, This song is vastly superior to the dreadful The Happening but that one reached number 1 and this one didn’t. Its a dark and eerie song that surely no one would have expected from Motown or the Supremes during that era. So yes, although personally i must put Stop! ahead of this, i would say it is their greatest song of all just for its unique, dark, sound.

LikeLike

When the Supremes began their unprecedented careers at the top of the charts, Diana Ross had that crystal clear soprano & enough charisma for 10 people & she became a star very quickly. I was in high school & she was a frequent subject of our conversations. We all loved the music. The girls were already seeing signs of the fashion icon she became & because of her energy & charisma — & Motown’s focus on quality — boys could be fans too,

Over the course of her long career, two things about Ms. Ross have become clear. One is that her phrasing is among the very best in the industry. People have always paid homage to Frank Sinatra for his great phrasing — & is was terrific — but, I think Diana Ross is just as good or better. It was years before I realized it, but it was on this record that I first took note of it.

Ms. Ross’ impeccable, unique phrasing is made more remarkable by her exemplary diction. This is a difficult song. As you pointed out, people do not say these things & not in this way. It might have sounded stilted or weird or not like a pop hit. But, in her interpretation, it sounds emotional, heartfelt & compelling. Through all the years of her career, Ms. Ross has worked hard to expand her vocal range, preserve the unique qualities of her voice & to even improve on the remarkable natural diction & phrasing abilities she displayed in 1965 on this recording. It is why she continues to play to sold out venues around the world at 79. We were lucky to see her perform this song in 2022 in New York City & it sounded as fresh & wonderful as on the 1965 recording.

LikeLike