Tags

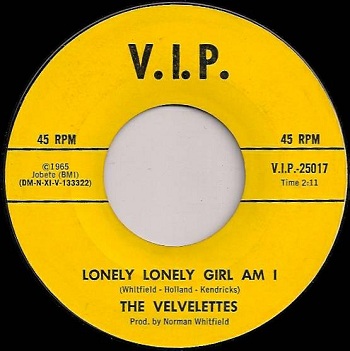

VIP 25017 (A), May 1965

VIP 25017 (A), May 1965

b/w I’m The Exception To The Rule

(Written by Norman Whitfield, Edward Holland Jr. and Eddie Kendricks)

Tamla Motown TMG 521 (A), July 1965

Tamla Motown TMG 521 (A), July 1965

b/w I’m The Exception To The Rule

(Released in the UK under license through EMI / Tamla Motown)

Not for the first time, the Velvelettes appear on Motown Junkies straight after a clunker from Howard Crockett. Back in December 1964, the girls had been called in to take away the unpleasant aftertaste of Crockett’s Put Me In Your Pocket, and responded with their best record yet, the thumping He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’. Now, after the borderline-unlistenable excesses of Crockett’s godawful All The Good Times Are Gone – a record so bad, it ended Motown’s involvement in the country market for a decade – it’s the Velvelettes to the rescue again.

Not for the first time, the Velvelettes appear on Motown Junkies straight after a clunker from Howard Crockett. Back in December 1964, the girls had been called in to take away the unpleasant aftertaste of Crockett’s Put Me In Your Pocket, and responded with their best record yet, the thumping He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’. Now, after the borderline-unlistenable excesses of Crockett’s godawful All The Good Times Are Gone – a record so bad, it ended Motown’s involvement in the country market for a decade – it’s the Velvelettes to the rescue again.

Crockett’s new record had been worse than his last one. In order to balance out the forces of the Motown universe, the Velvelettes would have to up the ante too; their new single, therefore, needed to be even better than their previous, magnificent effort.

And, somewhat unbelievably, against all odds, it is.

ALCHEMY

If I sometimes seem, on this blog, to be pushing a one-man effort for the re-evaluation of the Velvelettes, then you’ll have to forgive me. They were – are – magnificent. Rarely included in the conversation when people discuss Motown’s greatest groups, seldom even recognised as a Motown group at all, the Velvelettes disappeared from view in the mid-Sixties a quickly-forgotten footnote in the Motown story. But this oversight is a problem on the part of the world, rather than anything the Velvelettes did wrong; at their best, they could take on all comers.

(That’s not just a figure of speech. In February 1964, they and the then-similiarly-unknown Supremes took to the stage at Detroit’s Graystone Ballroom in what’s subsequently been called a “battle of the bands”, and the audience that day – so the story goes – preferred the Velvelettes. Of course, this was before the Supremes had any of their biggest hits in their repertoire – but then, the Velvelettes didn’t have their best material yet either.)

It’s history’s loss, really, that Norman Whitfield and the Velvelettes – whose partnership ended all too soon after the hits weren’t forthcoming and the group melted away – didn’t get the chance to work together for a few more years. Even in the short time that the maverick young producer and the maverick young group were paired together, they made such giant strides that it’s hard to imagine what might have happened had they remained a joint creative force.

Whitfield, a wisecracking loudmouth perfectionist, had rubbed a few people up the wrong way in his initial efforts to climb the Hitsville food chain, and he was assigned to the similarly misfit Velvelettes – something approaching Motown purgatory, as the group were not just unknowns but also frequently absent – in part as a way to keep him quiet. Perhaps liberated by the lack of profile on both sides of the glass, Whitfield started with a blank slate. He would quickly have realised that he’d hit the jackpot; the Velvelettes were educated middle-class girls who could not only follow direction but were smart enough to come up with their own good ideas, they were willing to “buy in” to what he was trying to do, and their harmonies were fantastic. When Whitfield then began working closely with the Funk Brothers rhythm section, sharing his cigarettes and booze – and royalties! – with the studio players, while explaining in painstaking detail not what he wanted them to do, but rather what he was trying to get them to do, the template was set, and just like that, the Motown Sound took another great leap forward.

Whitfield, a wisecracking loudmouth perfectionist, had rubbed a few people up the wrong way in his initial efforts to climb the Hitsville food chain, and he was assigned to the similarly misfit Velvelettes – something approaching Motown purgatory, as the group were not just unknowns but also frequently absent – in part as a way to keep him quiet. Perhaps liberated by the lack of profile on both sides of the glass, Whitfield started with a blank slate. He would quickly have realised that he’d hit the jackpot; the Velvelettes were educated middle-class girls who could not only follow direction but were smart enough to come up with their own good ideas, they were willing to “buy in” to what he was trying to do, and their harmonies were fantastic. When Whitfield then began working closely with the Funk Brothers rhythm section, sharing his cigarettes and booze – and royalties! – with the studio players, while explaining in painstaking detail not what he wanted them to do, but rather what he was trying to get them to do, the template was set, and just like that, the Motown Sound took another great leap forward.

The kind of muscular dynamism that propels so many great mid-Sixties Motown records, the physical thump and clatter of the backing tracks, the intricate weave of backing vocals trading places with lead parts, the blaring horns and sweeping flurries of strings that would soon come to define Motown every bit as much as the 4/4 beat and crotchet pulse that had stormed the charts in 1964… there’s an argument all of them can be traced back to the Velvelettes. And the Velvelettes didn’t benefit from being given great ideas; rather, those great ideas were recognised as great ideas because the Velvelettes had shown how incredible they could sound. All it took was a producer who knew what he wanted, and a group who could make it reality.

The magic of Lonely Lonely Girl Am I –

– I love that title, as though rather than call it “I’m A Lonely, Lonely Girl”, Whitfield and his co-writers (Edward Holland Jr. and, somewhat unexpectedly, the Temptations’ Eddie Kendricks) decided to favour killer scansion over more fiddly natural speech, gambling – correctly – that after you’ve heard the record even once, it’s done with so much confidence that you don’t even notice the odd title. But anyway –

– the magic of Lonely Lonely Girl Am I is in its immaculate construction. I know I’ve talked about Motown and magic before, and probably sounded just as crazy as I do now, but there’s something about a great Motown track, a quality in the air when it all hooks up, where complicated feats of musicianship and singing, and astounding jumps of imagination and melody, just feel absolutely effortless, so that you’re at once in awe of the genius it took to make this work and, simultaneously, carried along for the ride by the apparent ease with which it’s done.

If ever you wanted an example of this alchemy in action, look no further than this; the Velvelettes put on the greatest magic show we’ve ever seen.

NOT SO LONG AGO, I FELT COMPLETE

I like to think of Lonely Lonely Girl Am I as being like a fractal, one of those weird mathematical drawings where no matter how closely you zoom in, all the way down, thousands and thousands of times, you still see the same pattern. This record is made up of a whole load of different elements, put together very carefully in an intricate jigsaw puzzle (and not just any jigsaw; this one is on a par with a 20,000 piece job). Yet never do you get the sense that they’re anything other than parts of a whole, each of them expertly crafted with the finished product in mind. Every person does the best possible job they can do, but it’s all with one goal in mind, a cast of however many all at the peak of their game, directed by a man with a perfectly conceived master plan on a grand scale. This isn’t pop music, it’s architecture.

The dovetailing of all the ingredients that make up this record is a joy, both in its staggering effect and when you get it under the microscope to admire the workmanship. Using a string and bass refrain as half of a call-and-response in the verses, or having the Velvelettes send the chorus soaring up to the sky with a wordless vocal refrain requiring absolutely incredible timing to work, or – at the end – having Cal herself take over the vocal refrain instead? These are choices which feel both inspired and obvious.

Plus, everyone on this knows how good they are. The drums and tambourine are just out of this world. The Velvelettes have never sounded better, their harmonies like multi-coloured ribbons streaming through the sky, wrapping into spirals and loops and complex shapes and then gracefully unravelling like silk on silk. And Cal, who manages to best her incredible lead vocal performance from He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’, is mesmerising as she rolls the words around her mouth, sounding like a veteran singer twice her age as she purrs and growls her way through what might just be the best lead vocal we’ve yet encountered on any Motown record. The lyrics, full of wordplay designed for Cal’s tongue to pick through – “Sly but tender, you deceivingly surrendered your love to me” – exactly fill the allocated space in the track, with not a millimetre’s room for manoeuvre if you miss a cue. Faced with a challenge like that, Cal, of course, doesn’t even blink.

The end result? An absolutely killer tune, that Oh oh oh oh, doo-bee-doo hook guaranteed to stay in your head for weeks, performed in such a way that the bar is now set impossibly high for any female group to even think about covering this. What would be the point? It can’t get any better. The only Motown cover versions of this song are sung by men.

Unsurprisingly, despite receiving little push at the time, this has gone on to be an anthem on the Northern Soul scene, and the Velvelettes themselves speak fondly of it as the closest they ever got to making the record they wanted to make. As well they should: He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’ is a wonderful, wonderful record, well deserving of a place in anyone’s desert island collection – but with all due respect, this is their masterpiece.

There’s literally not one second, not one single second, of this record I’d ever change; it is, as far as I can tell, perfect.

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in The Velvelettes? Click for more.)

|

|

| Howard Crockett “The Great Titanic” |

The Velvelettes “I’m The Exception To The Rule” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

This one always seemed like standard mid-Sixties Motown to me (not a bad thing at all, of course) and nothing exceptional–possibly because it wasn’t a hit in my market (Los Angeles) as were “Sayin Somethin” and “Needle in a Haystack,” which will always be favorites of mine. I gave it yet one more listen based on your analysis and have to admit there’s more there than I had thought. I do love Cal’s phrasing and the way her voice works with the other girls. I would give it an “8”–it’s certainly a fantastic record.

LikeLike

10 out of 10 does it for me. It’s a Motown 45 that hits you right between the eyes. Lead voice is excellent as always and the bvs are spot on. How many times has this been said about artistes in the pop world? They should have been bigger than they were and have several gold records on their collective walls. Instead the Velvelettes, sadly, are often regarded as a footnote in Motown’s history. I’ve seen them perfom over here in the UK more than several times and they have never disappointed. They are truly a class act.

LikeLike

I’d never heard this one until I picked up a Velvelettes compilation ca, 2000. And I really couldn’t believe I’d never heard this before! Why wasn’t it a hit? I would have gone crazy for this had I heard it back in the day. I honestly don’t understand why it didn’t break. It’s such a quality piece of music.

But once I heard it, it was one of those things that I kept hitting the repeat button, just like in the old days when I kept playing a record over and over again until my parents would yell at me to stop. Love it. Is it a 10? It just might be. It’s definitely been short-listed. I’m still mulling over my top 50 and I still have a lot of weeding to do. But this is a prime candidate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent! I don’t envy you the process of having to drop beloved records – ones you’d assumed “Oh, this is a dead cert!” – simply because there aren’t enough spaces, but I love reading other people’s 50s.

This one – not that it makes any difference, there’s not meant to be an individual ranking within my top 50, they’re meant to be interchangeable, but anyway – this one was one of the very first names on the sheet, if anyone cares.

LikeLike

This was a thrilling critique of a thrilling record – one which I too discovered belatedly. I first became acquainted with the song through the Temptations ‘Gettin’ Ready’ album, and reveled in it as a part of a very nearly perfect LP – but when I picked up the Velvelettes 45, many years later in a second-hand shop, it blew the Tempts’ version out of the water. The Temptations’ version is a very pretty lament, but there’s fire, anger and MOVEMENT in the Velvelettes’ version – and it fully deserves a 10, even if it wasn’t among my 50 – your analysis makes me think it really should have been. Sorry, Shorty, but perhaps you’re about to be replaced!!

LikeLike

Thanks for leading off your radio show (#24?) with this song. I’d never heard it and it grabbed me immediately. I played it over and over, delaying my end of lunch embarassingly. The beat with the tamborine on the upbeat and guitar chicks on 2 and 4, the string and horn chords in syncopation, then the melodic string fills are so powerful, then the smooth lead vocal puts the unforgettable song firmly in my head. Stayed up til 2 am reading the reviews of 1965 last night. You’re a terrific writer, full of knowledge and passion for your subject. Gotta share with all my music friends!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And this is the sort of thing that makes it all worthwhile. Thanks for the kind words.

LikeLike

Reading the praise Steve D. has thrown upon this record that has never graced my ears made me anticipate this record. Will I praise this record like Steve or will I think what is he thinking? Are questions I asked myself before I listened to the song. My verdict: Steve D is RIGHT!!! This song is a mini masterpiece on record. Why this wasn’t a huge hit??? Escapes me. It has all the ingredients of a Motown classic. The singing is great, love that “I haven’t been able to sleep at night breakdown”, the instrumentation is great.. all the magic a Motown records has. I believe if another group male or female would have sung this song it would have landed on the charts.

LikeLike

Unbelievably, I just heard this one for the first time. Excellent record! I kind of understand why it probably wasn’t a crossover hit. Great as it is, it seems to have that extra helping of “soul” that sometimes kept great soul records from crossing over. After years of listening to top 40 music, rock, soul, etc, there seem to be certain ingredients to songs that are hits – that doesn’t always make the hit song a great song but most average Top 40 listeners seem to have limited attention spans & want a certain type of record. Thus, a lot of inferior songs become hits (though some great songs become hits as well). When I used to listen to Top 40 radio (in the late 60s/early 70s) many songs that appealed to me (& that I purchased) never became huge hits.

Anyway, all that said, this is a smokin song!

LikeLike

Smoking!

LikeLike

Hi D — Had to say something about the Inauguration Parade yesterday. I saw the Obamas watching the parade. Ms. Obama was clapping along with one of the marching bands. I could just imagine one of the daughters going “Mommmmmm! You’re embarrasing us!” LOL! Ms. Obama is rocking those new bangs! You go lady! Have a great day!

LikeLike

Hi Grandpa Landini! How are you feeling? Yes I saw the Inauguration Parade = ). I must first say Beyonce looked gorgeous and did a wonderful job with the Star Spangled Banner. As far as Mrs. Obama with those claps, I’m quite sure not 1, but both of the First Daughters were saying “Mom, you’re embarrassing us” lol. I love the First Family = )

LikeLike

I do believe the Temptations’ version was cut first, but I much prefer the song at this tempo; in fact it’s my favourite Velvelettes recording, my only criticism being that at 2 minutes 11 seconds it’s much too short.

A candidate for my Top 20 rather than Top 50, empatically 10/10.

LikeLike

2:11 leaves you screaming for more and hitting the repeat button (or leaving it on the record changer for another, and another spin. Stretching it out may have weakened it.

LikeLike

This is my favourite Velvelettes cut (and I like A LOT of them. I’d give it a 10 on a good day, and never less than 9.

LikeLike

It still baffles me why this didn’t at least hit Top 10 R&B. I guess by May, ’65, Gordy simply wasn’t allocating resources to \promote them when they were prioritized behind the Supremes, Vandellas & Marvelettes. Nevertheless, this track is arguably Cal’s best performance and ranks right up there with the best of the other girls groups. 10/10

LikeLike

How to improve a “10” recording? Give this “remix” a listen. This guy is a genius!

LikeLike

Disagree. One CANNOT improve on Whitfield & Velvelettes at their best. And why the sudden leap from mono to stereo at 0:45? Senseless (and I happen to prefer Hitsville’s stereo mixes from this period).

LikeLike

wzzzzz

LikeLike

Are you alright there, Michael?

LikeLike

This is an example of exactly the kind of review that, unintentionally, helps the new Mary Wells biography feel like there’s a little something ‘missing’ in the writing. Perhaps born too late to be of assistance in their heyday, The Velvelettes have nevertheless found their utmost champion. Bravo, Nixon.

LikeLike

There’s a lot missing in the Wells biography but it’s a decent first full-length write on her.

LikeLike

Meanwhile, in Jamaica:

LikeLike

Jimmy Ruffin sang an early male version.

LikeLike

Added Robb’s much-improved scan to the top of the review 🙂

LikeLike

Bam!! Easy 10!! Relentless beat, pure emotion, excellent musicianship. Play any 7 records surrounded by this one and its a sure beat The Velvellettes will be stuck in your brain for the next 24 hours. Quite a pleasant experience.

LikeLike

found this some years ago on “Hard to Find Motown Hits Vol.2”. One of my favourites and a definite 10/10.

LikeLike

Hmmm … well, the stunning lead vocal, the overall production, and the juxtaposition of vocals and instrumental lines are all at the 10/10 level, but the song itself sounds so much like On Broadway that I’m having a hard time getting as excited as everyone else, but given that everyone is on the same page, I will keep listening.

LikeLike

A great 10/10 Motown hit, don’t understand this not reaching Top 10 status in the US. Is this group a trio by this time, can someone please let me know. Or is it still Carolyn and Mildred Gill and the Barbee sisters? This is one of my favourite girl group singles form Motown mid 60s.

LikeLike