Tags

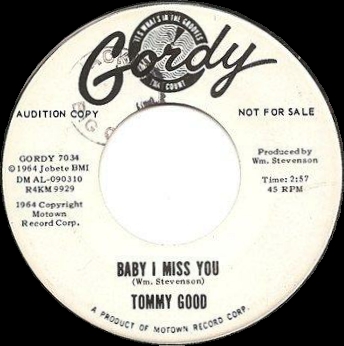

Gordy G 7034 (A), July 1964

Gordy G 7034 (A), July 1964

b/w Leaving Here

(Written by Mickey Stevenson)

Some records start off unassuming, then win you over, and then just keep on getting better and better the more you play them. (The Marvelettes’ You’re My Remedy is a prime example, though there are lots of others.) What starts out as a distraction, something that just passes you by on your first sweep through The Complete Motown Singles, ends up working its way into your affections until you realise you positively love the thing.

Some records start off unassuming, then win you over, and then just keep on getting better and better the more you play them. (The Marvelettes’ You’re My Remedy is a prime example, though there are lots of others.) What starts out as a distraction, something that just passes you by on your first sweep through The Complete Motown Singles, ends up working its way into your affections until you realise you positively love the thing.

This isn’t one of those records. This one started off grabbing my attention right off the bat – wow, who’s this? “Tommy Good”? Never heard of him. Was it a hit? No, apparently not. Well, did he cut any more Motown singles? Nope, this was it. Must investigate further. And so on. But the more I play it, the less and less I find it charms me, to the point I’m worried I’ll have to stop playing it altogether soon or I might find myself not liking it any more.

I do still like it a lot, mind you.

Tommy Good’s one and only Motown single saw the company making its first serious attempt to break a white R&B act since Debbie Dean three years previously. Motown certainly believed the lad had potential; not only did he cut reams of material over the course of a year at Hitsville, but he also saw one of the label’s more infamous publicity stunts set up in his favour. To launch Tommy’s solo career, Motown staged a mock “protest march” on the studio, featuring supposedly outraged die-hard Tommy fans (actually hired local schoolchildren) carrying picket signs demanding Motown release Good’s records.

A splendid specimen of Sixties astroturfing at its finest. In fact, Motown had planned the whole stunt from the start, using contacts in the local media to get coverage and build momentum for a complete unknown. Baby I Miss You was actually released less than a month after recording, Motown pretending to bow to nonexistent “popular demand” – but it’s interesting that they chose to mock up a fake backstory that claimed the song had been sat in the can for many months, because this probably would have made more sense in 1963. In several ways, it feels like a holdover from an earlier Motown era – this, of course, being a time when such things were measured in weeks rather than years.

To look at Tommy Good, pictured left, you might imagine him to have more in common with other white Motown signings like Bobby Breen, a dapper fellow with a handy line in slick MOR productions. In fact, Tommy turns out to be a skilled exponent of hard-edged blue-eyed soul, or what passed for hard-edged blue-eyed soul in the summer of ’64. Baby I Miss You is an almost mathematically perfect halfway point between Marvin Gaye and the Rolling Stones a few months previously, such that there are definite echoes (more than echoes, really!) of both Gaye’s Stubborn Kind Of Fellow and the early Stones’ covers of Come On or Not Fade Away.) With Beatlemania in the ascendancy in America, it’s not hard to see the possible future Motown had in mind for Tommy, and to be fair it’s not inconceivable he could have proved them right.

To look at Tommy Good, pictured left, you might imagine him to have more in common with other white Motown signings like Bobby Breen, a dapper fellow with a handy line in slick MOR productions. In fact, Tommy turns out to be a skilled exponent of hard-edged blue-eyed soul, or what passed for hard-edged blue-eyed soul in the summer of ’64. Baby I Miss You is an almost mathematically perfect halfway point between Marvin Gaye and the Rolling Stones a few months previously, such that there are definite echoes (more than echoes, really!) of both Gaye’s Stubborn Kind Of Fellow and the early Stones’ covers of Come On or Not Fade Away.) With Beatlemania in the ascendancy in America, it’s not hard to see the possible future Motown had in mind for Tommy, and to be fair it’s not inconceivable he could have proved them right.

This starts out great guns; the horns and the girls on backing vocals again sound superb, the drums are tough enough to match the swagger of either Gaye or Jagger, and if our Tommy seems to lack a little star wattage compared to frontmen like those, he makes up for it with a sturdy effort full of sweat and strain, complete with a game and gutsy Little Richard falsetto that hurdles over a fence many white performers had previously refused out of self-conscious embarrassment.

(Indeed, this is Motown’s first real attempt at the “white kid, black voice” phenomenon, and while I find myself wishing we could hear Marvin Gaye himself doing this – he’d have had a lot of fun with it, for sure – Tommy still turns in a credible enough effort that he deserves to have race left out of the conversation, even if at this stage he was enough of a rarity that it needs to be dragged up.)

It’s a fine lead vocal, and it adds up to a record that’s particularly hard to dislike; it’s a well-made single, and it’s made for an attack on the charts.

Had Baby I Miss You succeeded, had history gone in a different direction, it would have been well worth watching Tommy develop, especially if in that parallel existence Motown had competed with the British Invasion by means of providing their own flavour, something closer to the competition rather than a contrasting vision for the future of pop. The material gathered on Tommy’s Motown Collection anthology (above), all recorded between 1964-65, tends towards more of the R&B sounds assigned to every other Motown act of the time, although there are some killer cuts on there – his staggering, echo-drenched West Coast take on Ed Cobb’s Give Me Something (9), predating R. Dean Taylor’s version and mixing in more than a dollop of the Supremes’ Where Did Our Love Go, is worth the price of admission on its own, though sadly it doesn’t appear to be available for hearing on Youtube. But we’ll never know what he might have gone on to do. I’d have certainly been intrigued to hear what Tommy’s records sounded like in 1968.

But no. The single stiffed, and there would be no more Motown releases for Tommy Good, the project abandoned much too quickly. Perhaps they’d spent too much money on that fake protest march or something. Or, getting more to the heart of the matter, perhaps Motown felt there was no role for a would-be pop star if his records didn’t sell straight away. It wasn’t 1961 any more; the Supremes, Temptations and Tops had all finally achieved their breakthroughs, and Motown had little motivation to invest another three years in another act struggling for chart success.

But no. The single stiffed, and there would be no more Motown releases for Tommy Good, the project abandoned much too quickly. Perhaps they’d spent too much money on that fake protest march or something. Or, getting more to the heart of the matter, perhaps Motown felt there was no role for a would-be pop star if his records didn’t sell straight away. It wasn’t 1961 any more; the Supremes, Temptations and Tops had all finally achieved their breakthroughs, and Motown had little motivation to invest another three years in another act struggling for chart success.

If it’s not difficult to see this succeeding, it’s also not so difficult to see why it didn’t; the song doesn’t bear super-close examination (as in the sort of super-close examination teenage girls will give a record when they’re playing it six hundred times in a row before it wears out) and it’s not long before it starts to unravel.

The lyrics are very silly indeed; the first few listens, I thought this was a post-breakup song of contrite and desperate pleading, Tommy’s narrator begging his girl to come back and give him one more chance. On closer inspection, it’s actually Tommy’s narrator begging his girl to come back from a short trip to Louisiana to visit her estranged family, because he misses her. On even closer inspection, she appears to have only been away for a few hours, and so Tommy’s impassioned plea becomes a whiny, neurotic whinge from a man so insecure he can’t even spend one night alone. (And he’s not even going to try – even though it’s obviously important to her to make this trip, he’s willing her to turn round and come back to him. She’s lucky they didn’t have cellphones in 1964.

(BZZZZZT! BZZZZT! BZZZZZT!)

INCOMING CALL: Tommy (Home)

[Ignore]

You have 38 missed calls

Turning the narrator from a hearthrob to a drip is not a good move for Tommy’s teen-idol prospects, and it doesn’t do the song any favours either. It’s not long before you start noticing the little deficiencies in the vocal, catch yourself thinking “Marvin wouldn’t have done it that way”, not making allowances for this being the poor boy’s début. For instance, there’s a bit where Tommy refers to himself in the first person, something I usually love (“I told myself: it’s alright / You’ll miss her lovin’ for just one night / Tommy, you can take it, I know you can / Just stand up like a natural man“). Big smile. But the next line is about how hearing her close the door made him break down and cry, and armed with that knowledge it’s hard to hear it the same way again.

Still, the record wasn’t made for lyrical trainspotters, and for the most part it all sounds really, er, good. Textual silliness aside, it’s very hard to dislike, and while I’m glad we have the Motown Collection CD to throw the vaults open and provide a glimpse of what might have been, I’m definitely a little sad we won’t meet Tommy Good again on this Motown journey. A highly creditable first step, and it’s a real shame there isn’t a second.

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in Tommy Good? Click for more.)

|

|

| Martha & the Vandellas “There He Is (At My Door)” |

Tommy Good “Leaving Here” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

It’s one of my favourite Motown cuts, and the best song Mickey Stevenson wrote as a solo writer. I’d give it a 9. Motown didn’t plug this song, nor Tommy AT ALL (outside Detroit). So, it’s no surprise that it flopped. I bought it as soon as it was released and in the shops. I had a friend who worked in a record shop, who introduced me to each new Motown release that made it to the shops.

think Tommy also did a very good job on a few of his unreleased Motown cuts. I’d rather have heard The Spinners or Monitors (Richard Street) sing that song than Marvin Gaye.

LikeLike

Give me something is “really something”, a true buried treasure. Many thanks for the discovery !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always happy to be of service 🙂

LikeLike

For anyone who wants to familiarise themselves with the work of songwriters Staunton & Walker, there are five of their compositions on Tommy Good’s Motown Collection.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nixon, you’re review of this is spot on. I with you for 7/10. Tommy’s vocal is fine but there’s something missing in the production for me. The hook is not quite there. Motown did promote the record nationally in Billboard but it didn’t click.

LikeLike

I wonder who the back-up singers are. I don’t think it’s The Andantes this time. They still do a good job!

LikeLike

They sound to me like Martha and The Vandellas.

LikeLike

I don’t hear Martha or Rozzie. Maybe it’s The Velvelettes? They’re good with harmonies, too. It’s just a guess, of course, but it’s the best I’ve got. I don’t think they had a high soprano in their group, though, so maybe Louvain Demps is singing with them, ’cause I think I hear her.

LikeLike

CORRECTION: The Velvelettes had a soprano. I could hear it on “Lonely, Lonely Girl am I”. But I still think Ms. Demps might be on this record.

LikeLike

“Rozzie”?

Ms Ashford has been known to read and comment on this site. Some respect, please.

LikeLike

Sorry. I will try to remember my etiquette in the future.

LikeLike

🙂

LikeLike

Now that I think about it (and have listened to more of The Andantes), it probably is them. How could I have been so foolish?!

LikeLike

Tommy himself has said it’s the Andantes.

LikeLike

Sir, you have just given me something to order on my weekly visit to CD island.

LikeLike

A lot of Mr. Good’s unreleased work is incredibly good. I hope you enjoy it. I strongly recommend “I’ve Got to Get Away” and “You’re Something to Talk About”. The whistles at the end of the latter song always puts a smile on my face!

LikeLike

Tommy’s unreleased cuts are some of the best of the Motown vaults. I remember getting the CD when it came out in 2005 and listened to it like crazy that entire summer. Tommy is a super nice fella, I was fortunate enough to speak with him a few times!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just played this on the radio show today, and we got a text afterwards from someone saying they loved it, so there’ll be plenty more Tommy in the coming weeks. Mr Good, are you still listening out there?

LikeLike