Tags

Tamla T 54122 (A), September 1965

Tamla T 54122 (A), September 1965

b/w She’s Got To Be Real

(Written by Smokey Robinson, Pete Moore, Marv Tarplin and Bobby Rogers)

Tamla Motown TMG 539 (A), November 1965

Tamla Motown TMG 539 (A), November 1965

b/w She’s Got To Be Real

(Released in the UK under license through EMI / Tamla Motown)

1965 is the year Marvin Gaye became Marvin Gaye, or at least the Marvin Gaye we now know. He’d had success before, commercially and artistically, but it’s here in ’65 that he really begins to explore, try out new things, new ideas, taking steps that we can identify with hindsight as being steps towards his future; in ’65, we finally get to meet the finished article hip-shaking superstar sex symbol, as well as being able to see the path from here to the “tortured genius” social and sexual conscience of the 1970s. Not bad for a session drummer and Nat King Cole wannabe.

1965 is the year Marvin Gaye became Marvin Gaye, or at least the Marvin Gaye we now know. He’d had success before, commercially and artistically, but it’s here in ’65 that he really begins to explore, try out new things, new ideas, taking steps that we can identify with hindsight as being steps towards his future; in ’65, we finally get to meet the finished article hip-shaking superstar sex symbol, as well as being able to see the path from here to the “tortured genius” social and sexual conscience of the 1970s. Not bad for a session drummer and Nat King Cole wannabe.

Marvin’s last two singles for Motown in 1965 have showed us two divergent paths; the radio-blasting R&B-pop of I’ll Be Doggone had seemed to lay out a clear set of directions for him to follow, mapping out his career as the guy who jumps around the stage and whips the crowd into an ecstatic frenzy. But then, the strange, beautiful follow-up Pretty Little Baby – with lyrics by Gaye himself – saw him in reflective, serious mode.

As much as I adore Pretty Little Baby, there’s little argument that it represented a break in what seemed like a well-worked plan, a juddering change of tack rather than a consolidation of Marvin’s newfound stardom. Not surprisingly, the record had baffled the fans, and Motown took quick action to put him back on course again. As with every other act on the label’s books, Motown did what they always did whenever an artist needed material and guidance: they called in Smokey Robinson.

Smokey and his Miracles bandmates had penned I’ll Be Doggone, and so it’s no surprise when Ain’t That Peculiar immediately sounds like a continuation of the work they’d started there; Robinson must have relished the chance to carry on what they’d begun, and Marvin seems to have been grateful to see where they wanted to take him. Which, as it turned out, was straight back to the top of the R&B charts, a second Number One (and a Top 10 pop hit) to go with I’ll Be Doggone. Easy when you know how.

It helps that it’s another very good song, of course, and Marvin has a blast with it, back in the groove as though he’d never deliberately stepped out of it in the first place. This time, though, there’s no dubious lyrical content to trouble the listener, no sense of clouded purpose; it not only sounds better and sharper than I’ll Be Doggone, it’s also catchier and livelier.

Most importantly, though, Marvin’s more comfortable in his pop star skin than ever before; I don’t know if seeing Motown approve a less overtly pop-friendly (and partly self-penned!) single like Pretty Little Baby had reassured him that making interesting records wasn’t incompatible with his swaggering new role, but he sounds happier to be doing an upbeat rocker than we’ve ever heard him before, more than Stubborn Kind Of Fellow, more than Baby Don’t You Do It. I don’t mean he sounds incongruously chirpy given Smokey’s intriguing lyrics, I just mean he comes across as though there’s no hint of him finding this demeaning in some way, and that’s a delicious relief.

Most importantly, though, Marvin’s more comfortable in his pop star skin than ever before; I don’t know if seeing Motown approve a less overtly pop-friendly (and partly self-penned!) single like Pretty Little Baby had reassured him that making interesting records wasn’t incompatible with his swaggering new role, but he sounds happier to be doing an upbeat rocker than we’ve ever heard him before, more than Stubborn Kind Of Fellow, more than Baby Don’t You Do It. I don’t mean he sounds incongruously chirpy given Smokey’s intriguing lyrics, I just mean he comes across as though there’s no hint of him finding this demeaning in some way, and that’s a delicious relief.

It’s a fine record, this. Much has been made of Smokey’s wordplay and rhymes, but those are almost second nature to Robinson now, and Marvin navigates them with gusto (other than the slightly clunky and confusing phrase which I’d been hearing as A peculiar allergy – but consensus in the comments section has Marvin adding a syllable to the word “peculiarity”, which makes slightly more sense!)

Rather, it’s the structure of the song which really allows Gaye to come into his own. As with so many of his best hits to date, the rolling, chiming repeated riffs that underpin the song allow Marvin to float over the top, giving him room to extemporise with his his vocal as and when he feels the need without it coming across as self-indulgent. It’s a recipe that later comes to the boil in One More Heartache, but this is the best example of it so far, and Smokey and the Miracles stock the cupboards with hooks and tricks to boost the signal: a riveting pre-chorus break, a series of infectious call and response Ah-ah-ah!s, a backing vocal-led chorus that must rank among Smokey’s catchiest efforts. Even the band are having a blast, James Jamerson’s wandering bass used sparingly before cutting out altogether, piano pounded and pounded to within an inch of its life.

Not for the first time, Marvin Gaye sounds every inch the pop superstar, and once again here he’s made an excellent pop record. The difference, now, is that he’s making excellent records that sound like Marvin Gaye records, and everyone else is hereby put on notice.

MOTOWN JUNKIES VERDICT

(I’ve had MY say, now it’s your turn. Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment, or click the thumbs at the bottom there. Dissent is encouraged!)

You’re reading Motown Junkies, an attempt to review every Motown A- and B-side ever released. Click on the “previous” and “next” buttons below to go back and forth through the catalogue, or visit the Master Index for a full list of reviews so far.

(Or maybe you’re only interested in Marvin Gaye? Click for more.)

|

|

| The Supremes “Things Are Changing” |

Marvin Gaye “She’s Got To Be Real” |

DISCOVERING MOTOWN |

|---|

Like the blog? Listen to our radio show! |

| Motown Junkies presents the finest Motown cuts, big hits and hard to find classics. Listen to all past episodes here. |

“…(other than the slightly clunky and confusing phrase A peculiar allergy!, which still doesn’t make a lot of sense)…

Seriously? Um, I think the lyric is “A peculiarity.”

LikeLike

Great essay, as always. I’d bump this up one to a “9.”

I agree with Robert about the lyric. I think Marvin (or Smokey) adds an extra syllable and the word becomes “peculiar-arity” or “peculiar-ality.”

LikeLike

Ha! I don’t know how many dozens of times I’ve listened to this, but it’s clearly not enough 🙂

So what do we think: is he singing “Peculiarality” on purpose, or is it a flub…?

LikeLike

I just gave it a listen. I’m hearing “a peculiar allergy” in the first chorus, and “a peculiarality” [sic] in the second and third.

Incidentally, not to derail the thread, but in the instrumental track I’m hearing one of those little “peculiaralities” that can make musos wince: Without going into tedious detail, I’ll just say that the highest note of the song’s main instrumental hook is an A natural, which is always accompanied by an inappropriate G# in the bass – and this happens again and again throughout the song. It’s undoubtedly one of those tiny errors that can easily slip by on the hitmaking assembly line (when the bass is involved, even fairly keen-eared listeners can sometimes fail to catch little mistakes), and not egregious enough to ruin the performance by any means.

LikeLike

I’m hearing peculiiar-arity each time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Given Smokey’s penchant for wordplay on occasion, “peculiar-ality” does sound very plausible in this context. Almost like Neil Diamond’s use of the word “brang” in “Play Me.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

>I’m hearing peculiiar-arity each time.

Me too. I think he’s singing the dictionary word peculiarity, which would work as 6 syllables: pe cu li a ri ty, but hanging out on “li” wouldn’t sound idiomatic so he’s pronouncing it pe cu liar a ri ty – adding the “r” sound. It’s like saying “axe” for “ask”. Remember that the English language has historically sucked for music – as I pointed out early, just look at the list of great operas. It was a major linguistic miracle that Afro-Americans transformed English into the world’s go-to language for music. For English to beat the eminently musical Italian is like the 62 Mets beating the 27 Yankees. But Afro-American English has different rules of pronunciation (and exceedingly different verb structure!) But I also really like W.B.’s idea that it’s one of Smokey’s “coined” words.

LikeLike

I’ve heard “axk” a lot more than “axe” (but a lot of people do say “axe”). These pronunciations come from the basic sounds used in West African Guinean and Bantu languages. Mary Wells said “axk”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great record! The call-and-response reminds me of “What’d I Say,” and shows that Smokey could find inspiration wherever there was a good source.

I’d call this a “9” after considering it for one of my Top Fifty and having second- (or third-) thoughts.

LikeLike

I don’t post much nowadays, but I always heard it as “a pe-cul-i-ar-i-ty” which fits with “pe-cul-iar-as-can-be”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Post more! We miss you!

LikeLike

Sure! It’s just that another commenter usually says what I would have, and does it better. In any case I’m still here, reading.

LikeLike

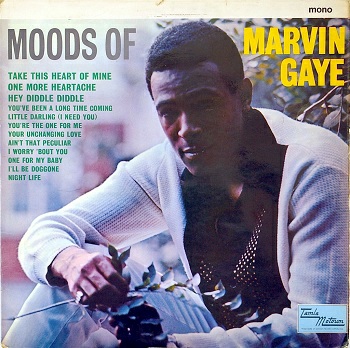

Wow! This is a great record. Great production. Boy, that “Moods of Marvin Gaye” album was packed with hits. At least 7 songs trom that album wound up on his “Greatest Hits Vol 2” collection.

LikeLike

I agree, Landini!! “Moods Of Marvin Gaye” is an essential..”Little Darling I Need You” “Your Unchanging Love” ” You’ve Been A Long Time Coming” the B-side of “I’ll Be Doggone”, Great H-D-H material!! an 8 or 9 is fine with me on “Ain’t That Peculiar”

LikeLike

Interesting that Motown tried to re-tool this song a couple of times. There was a pretty awkward version on Jermaine Jackson’s first solo album. I actualy like a lot of Jermaine’s solo stuff but this particular song just didn’t fit his style. Later in the early 80s Jose Feliciano did a version on one of his Motown albums which was a bit 80s-ish but not bad.

Back to Marvin’s version, I could definitely see people dancing to this one in the early discotheques.

Re. the MOODS album there is a great hidden treasure on there called “You’re the One for Me”. Great tune.

LikeLike

Yeah I hated that Jermaine cover, but one of my favorite Jackson 5 covers is “Love’s Gone Bad”

LikeLike

Yeah, poor Jermaine gets a bad rep. Everyone compares him to brother Michael. Fact it, Jermaine has a lot of talent & has made some good records. I think as his voice matured Jermaine got better. Poor Jermaine, I remember him struggling through “Bridge Over Troubled Water” on the 3rd Album. But then he did an awesome take on “16 Candles” on the next album

I remember playing Jermaine’s J-5 tune “I Found That GIrl” & my dad happend to be nearby & said “Who is that singing? He is horrible!” C’mon dad… Ha ha ha I think it is a sweet little song. I always liked it when Jermaine & MJ would trade off lines in the same song like “Suger Daddy” That song was da bomb! I was in 8th grade choir at the time & I used to try to sing the harmonies on that song.

LikeLike

LMAO! Dang to your dang. I actually think Jermaine did an okay job with “I Found That Girl” he always sounded older than his teenage years to me. Now “Bridge Over Troubled Water” & “16 Candles” I have always skipped over. I’ve never cared really for J5 songs that Michael wasn’t singing the lead. I, too, love the trade off lines between Michael & Jermaine also liked it when Jackie would get thrown in the mix. Older Jermaine I like the song “I Know You Like Me” and “Do What You Do”. I also liked him and Michael’s duet “Tell Me (I’m Not Dreaming” should’ve been a single and I have to say Michael killed that track! = )

LikeLike

Tamla 266, no question about it. I’ve never been without a copy of Moods since 1966. When it comes to an album chuck-a-bloc with hits, Moods is to Marvin’s roster what Shotgun is to Walker’s. It even got a couple standards folded in, which we know by now had to please Marvin.

LikeLike

LOL @ “peculiar allergy”! I am pretty sure it is just a case of popping an extra “r” in pe·cu·li·ar·i·ty. Whatever he says, it’s a great song. I also love Martha Reeves’ plot twist on the song.

LikeLike

This is one of the great Marvin Gaye tracks. And one of the great Smokey productions. I’d give it a 10 but then my top 50 would be too Marvin Gaye-laden. But it’s definitely a solid 9.

And a measure of my esteem for you, Nixon: when you made the comment on “peculiar allergy”, my immediate thought was, “have I been hearing it wrong after all these years?”

But I was pretty sure it was a peculiarity.

LikeLike

I first heard this song while soaring across the Walt Whitman Bridge in my car (bye, bye, New Jersey, I’ve become airborne – thanks to Marvin, Smokey, Jamerson, and others!) and it hasn’t lost even the tiniest fragment of its joyful tragic energy. Yeats’ poem ‘Lapis Lazuli’ talks about the paradox of our pleasure in tragedy – ‘gaiety transfiguring all that dread.’ – The last line is about a sculpture of Chinese musicians, asked to play mournful melodies: ‘their eyes, their glittering eyes are gay.’ The sparkle in Marvin’s eyes while he sings this is palpable. A ten for me too – to be followed by another, in ‘One More Heartache’ – two of his (and Smokey’s) very best. By the way, I’m fascinated by the discussion of ‘peculiar allergy/peculiarity’ – I had always thought it was a slightly jumbled ‘peculiarity’ – but that didn’t make too much sense, given the razor-sharp clarity with which Marvin delivers the rest of the song.

LikeLike

Yes, John, “One More Heartache” is a great song. I’ll wait until it shows up to comment further. I really envy you guys who heard these songs when they first came out. I didn’t start hearing new Motown songs until late 1967! In fact, I didn’t realize that Marvin Gaye had done solo songs. I first thought he only recorded duets with Tammi Terrell! I think the first solo song by him that I heard was “You”.

It is amazing at how many people aren’t aware of MG’s music beyond “Grapevine” etc. I remember being in the car with a friend when MG died & they were playing “I’ll Be Doggone” on the radio. My friend said something like “What song is this? Is this Marvin Gaye?” I told my friend that MG made 2 Greatest Hits Albums prior to “Grapevine”! Some people seem to think he just walked in off the streets & recorded “Grapevine”. Oh well. I’m useless in conversations about sports!

LikeLike

So is John (useless about sports conversations) if it makes you feel any better! I’m okay with the 8 – love this song but really, really love One More Heartache!

LikeLike

I was going to recount how I took my brother to a hockey game when he visited Montreal, and couldn’t understand why everyone was leaving after the third quarter. Bob still ribs me about it…..

LikeLike

Cool! I thought I was the only person on the planet who liked “One More Heartache”.

LikeLike

It’s “Take This Heart of Mine” that I really like.

LikeLike

Yes, Yes!! “You Are The One For Me” …That is another cut I thoroughly enjoyed! Infact, I can still hear it in my head as I’m writing this..As far as “Ain’t That Peculiar”, this is better listened to in the Single mix! The rythmic clapping in the back up are so crisp and clear!!

LikeLike

How about that “Hey Diddle Diddle” MG was the only singer who could make a soulful tune out of a nursery rhyme!

LikeLike

Totally one of my favorites!

LikeLike

When I first read “peculiar allergy,” I too figured I had just been hearing it wrong for all these years! I always just assumed the lyric was “peculiar as can be,” but I never quite liked it that way. Only recently have I heard it as “peculiarality,” which finally sounds right to my ears.

As Smokey/Marvin/etc’s proper follow-up to “I’ll Be Doggone,” this song is everything that song fell short of being. These two have always been associated with each other in my mind, even before I had any idea where they fell in Marvin’s chronology, and “Ain’t That Peculiar” has always been the clear winner. But of course my local oldies station always seemed to have just the opposite opinion – playing more “Doggone” than “Peculiar” – to my frustration!

Has anyone heard Neil Diamond’s “Shot Down” from 1967? Neil (or one of his New York session guys) must’ve had the intro riff to “Ain’t That Peculiar” in mind…

LikeLike

🙂 I agree wholeheartedly. Lyrically, a completely understandable sermon about the duality of love that gets better the more personal relationship history one accrues. You commiserate with Marvin’s experience and he commiserates with yours, like buddies. All that’s missing is a pair recliners and a drink for Marvin and a drink for you. And with Smokey’s sure hand in there, there was little chance of less than a totally delightful record.

There’s a point in David Ritz’s “Divided Soul.” where Marvin talks about painful bunions on his feet that would force him sometimes to walk slow. Smokey notices and says “you walk just like an old man. I think I’ll call you ‘Dad.'” And so their private nickname was minted. One gets the unmistakable impression in the book that Smokey knew just how to stroke and appease Marvin’s ego, and coax the very best work out of him on Smokey’s material. The results inarguably back that up.

Like all the best of them, this is another Motown record that time can never do any damage to. This one will keep winning fans long after we’re gone.

LikeLike

I like this waaay “I’ll Be Doggone” I must start off saying. That bass is out of this world. Lyrically it’s witty and smart. Marvin’s vocals evoke the right smoothness and pian and even humor.

LikeLike

Don’t know if you Junkies have heard this

LikeLike

Brilliant! Thanks, Damecia!

LikeLike

Every time I hear this song I wonder what a Mary Wells version would have sounded like. There’s something about this record – the word play, the Andantes’ individual repeat of words like stronger and longer – that just makes me think of her. Good song. An 8 or 9 for me.

LikeLike

Hi Junkies!

A little off topic (those of you who read the comment sections know I can be a little off topic most times lol) but I was listening to some oldies today and I stumbled upon a Tammi Terrell song that I like very much called “I Can’t Believe You Love Me” . I don’t know if Steve will cover this song, but the bass line reminds very much of “My Girl”

Any thoughts? (You know I love when you guess add your 5 cents lol)

LikeLike

It’s due to be review 656, so let’s all keep our powder dry until we get there 🙂

LikeLike

LOL okie dokie!

LikeLike

Love , love this song. From the piano and guitar chords in the intro complimenting the harmonies of the Andantes throughout . Arguably, one of Motown’s best productions. Despite Smokey’s “peak reality” ,He seems a lot less stressed to be clever. I can’t wait for your review of “One More Heartache.” Good Job!

LikeLike

And ” Little Darlin'( I Need You)” Oh, the time creeps by.

LikeLike

The posting of the acapella version means I have to remind you of the Marvin Gaye DVD that Motown brought out in the UK.. Inner City Blues and What’s Going On are two stand outs from the Acapella tracks. Also if I may could I mention George Tindley’s version of Ain’t that perculiar. Hoping I’ve broke no site rules.

LikeLike

🙂 Not at all – we’re an easy going bunch by and large 🙂 The only “rule” is that we can’t post links to the audio/video of the song actually being discussed.

There’s also a convention that we don’t talk in depth about upcoming singles/B-sides, but that’s just so we’ll have stuff to talk about when we get there. Otherwise, fill your boots 🙂

LikeLike

I just heard the Delfonics’ version of this yesterday. Love the Delfonics but it isn’t a very good arrangement & doesn’t fit their style.

LikeLike

Maybe its me or just the passage of time. I heard it too much perhaps?

I like the lyrics and all but the song just doesnt knock me out, say the “Pride and Joy” or “Hitch Hike” does. Its not the last marvin single i would reach for but its not the 1st or 2nd either. Can’t explain it.

Anyway i went to a party two weeks ago and “Hitch Hike” came on. Boy did the floor smoke!!!

LikeLike

“When it comes to a number that crackles like a blue firework, then our Marvin has no peers, and it does my old heart good to hear him pounding out in the same bag as his former all-happening rhythm numbers. Marvin can sing pretty ballads too, but oh, how I prefer it when he swings, and his voice loop de loops in and out of the strong rhythmic cross currents. Super. 5/5

“[Flip] 3/5”

[Dave Godin, Hitsville USA 10, 1965]

LikeLike